An Intro to Freud Is Not an Intro to Contemporary Psychoanalysis

Reviewing Paul Bloom on Freud and the unconscious

In an earlier post I discussed the chapter on mental disorders from Paul Bloom’s book Psych: The Story of the Human Mind. In this post, I will discuss Bloom’s chapter “Freud and the unconscious.”

The central point of my commentary is that, due to a narrow focus on Freud, Bloom loses sight of the current state of psychoanalysis and what it has to offer, both clinically and scientifically. Since the chapter on Freud is the only substantive discussion of the psychodynamic approach in Psych, the reader is left with a distorted idea of the current standing of the field. Furthermore, the emphasis on Freud’s theoretical idiosyncrasies at the expense of contemporary psychodynamic thinking is not something specific to Bloom; it’s representative of the current state of academic education in psychology.

The chapter itself is well-written, accessible, and enjoyable. It should be taken into account that Bloom has worked and taught in a context that is hostile to Freud’s legacy, and resultantly, Bloom is generally on the backfoot in this chapter, trying to justify to an unsympathetic reader why he takes Freud seriously to begin with. In this sense, even though I argue that he doesn’t do justice to contemporary psychodynamic thinking, Bloom is nonetheless an ally to those who protest the eradication of Freud from scientific curricula.

“Students are often surprised that psychology departments seldom have courses on Freud; actually, you can get an undergraduate degree in psychology at a major university without hearing his name ever spoken. (There is more interest in the humanities—you’re more likely to find an English professor talking about Freud than a psychologist.) When I was starting out as an assistant professor at the University of Arizona, I taught a seminar called Darwin, Freud, and Turing: Three Perspectives on the Mind, and more than one of my senior colleagues told me that it would be a better course if I took out the man in the middle. Many psychologists would concede that the psychodynamic movement founded by Freud is an essential part of the history of our field—but they see it as an embarrassment, like a pharmaceutical company that got its start by selling meth.” (pp. 56-57)

Bloom discusses how many of Freud’s ideas, such as penis envy and castration anxiety, are “strange” and scientifically problematic, if not outright discredited, but, “Despite all this, I believe that there is a lot of value to Freudian thought. I think we can retain some of the core insights of his theory and jettison the silly stuff. This is what many of Freud’s own followers did.” (p. 57) So far, so good, except that there is very little subsequent discussion of what contemporary psychoanalysis looks like once we jettison the “silly stuff.”

Bloom does get the central thing right about Freud’s legacy:

“For me, the best idea that remains is the notion of an unconscious mind at war with itself. For Freud and his followers, we are not singular deliberating beings. Rather, each of us is driven by internal turmoil, much of which is hidden.” (p. 57)

A big emphasis of Bloom’s discussion concerns the falsifiability of psychoanalytic thought:

“We should suspect theories that cannot be proven false… This brings us back to Freud. One of the main criticisms of Freudian theory is that it’s unfalsifiable. This is clearest in examples of therapeutic insights. Imagine dealing with a therapist—suppose you are treated by Sigmund Freud himself—and he says that at the root of your problems is hatred of your father. And suppose you are outraged and angrily deny it. Freud could say, “Well, your anger shows this idea is painful for you, which is evidence that I am right.” But Freud would also see support for his idea if you had said nothing or if you agreed with him. There isn’t really anything that could prove him wrong. Indeed, Freud could have said the opposite—that you have an unhealthy romantic obsession with Dad, you love him too much—and he would have taken the very same responses as support for that view.” (pp. 65-66)

Bloom quotes from Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams to illustrate that this isn’t exactly a caricature, that Freud did in fact come up with hypotheses of this sort in his interactions with patients based on extraordinarily flimsy evidence.

“This falsifiability objection is powerful, but a defender of psychoanalytic theory could object that much of it pertains to the practice of Freud and his colleagues, about how they treat their hypotheses. In the hands of an objective scientist, Freud’s actual theory seems to make falsifiable predictions… So we can derive falsifiable hypotheses. Unfortunately for the Freudians, none of these claims has real empirical support. In general, when you test such Freudian hypotheses empirically, they do poorly.” (pp. 66-67)

Bloom’s examples of empirical demonstrations are less than persuasive, however: a study showing, e.g., that there is no excess preponderance of “phallus-shaped foods” in dreams, and that the majority of typing errors (a proxy for Freudian slips) do not have sexual content.

Bloom’s grimly concludes, “Overall, Freudian theory is either vague or unsupported by the evidence. This is why we no longer study Freud in most psychology departments.” but argues that Freud is still important for the following reasons:

Freud is an important thinker in Western history

Freud was a wonderful writer

Freud’s openness to sexuality was transformative and liberating

Most importantly, Freud’s “grand idea of the primacy of the unconscious lives on.”

If I had to recommend one reading as an introduction to contemporary psychodynamic thought, it would be the 2022 article “That was then, this is now: psychoanalytic psychotherapy for the rest of us” by Jonathan Shedler in Contemporary Psychoanalysis. (It is an abridged version of a longer document available on Shedler’s website. I also interviewed Shedler for Psychiatric Times in 2020, “Psychoanalysis and the Re-Enchantment of Psychiatry.”)

Here’s the abstract, which deserves to be reproduced in its entirety:

“Psychoanalysis has an image problem. The dominant narrative in the mental health professions and in society is that psychoanalysis is outmoded, discredited, and debunked. What most people know of it are pejorative stereotypes and caricatures dating to the horse and buggy era. The stereotypes are fueled by misinformation from external sources, including managed care companies and proponents of other therapies, who often treat psychoanalysis as a foil and whipping boy. But psychoanalysis also bears responsibility. Historically, psychoanalytic communities have been insular and inward facing. People who might otherwise be receptive to psychoanalytic approaches encounter impenetrable jargon and confusing infighting between rival theoretical schools. This article provides an accessible, jargon free, nonpartizan introduction to psychoanalytic thinking and therapy for students, clinicians trained in other approaches, and the public. It may be helpful to psychoanalytic colleagues who struggle to communicate to others just what it is that we do.”

In the illuminating discussion that follows, Shedler argues that the legitimacy of contemporary psychoanalysis does not depend on ideas about id, ego and superego, or fixations, repressed memories, etc., but on core ideas that are clinically sensible and have broad empirical support. I strongly recommend reading the entire article, but for the benefit of readers, I’ll list the core ideas of psychoanalysis from the article using Shedler’s own words:

Unconscious mental life. “We do not fully know our hearts and minds, and many important things take place outside awareness. This observation is no longer controversial to anyone, even the most hard-nosed empiricist. Research in cognitive science has shown repeatedly that much thinking and feeling goes on outside conscious awareness… Psychoanalytic discussions of unconscious mental life do, however, emphasize something cognitive scientists tend not to emphasize: It is not just that we do not fully know our own minds, but there are things we seem not to want to know.”

The mind in conflict. “humans can be of two (or more) minds about things. We can have loving feelings and hateful feelings toward the same person, we can desire something and also fear it, and we can desire things that are mutually contradictory.”

The past lives on in the present. “Through our earliest experiences, we learn certain templates or scripts about how the world works… We continue to apply these templates or scripts to new situations as we proceed through life, often when they no longer apply. We view the present through the lens of past experience—and therefore tend to repeat and recreate aspects of the past.”

Transference. “A person starting therapy is entering an unfamiliar situation and a new relationship and necessarily applies their previously formed templates, scripts, or schemas to organize their perceptions of this new person—the therapist—and make sense of the new situation.”

Defense. “Once we recognize there are things we prefer not to know, we find ourselves thinking about how it is that we avoid knowing. Anything a person does that serves to distract their attention from something unsettling or dissonant can be said to serve a defensive function.”

Psychological causation. “it is our working assumption that symptoms have meaning, serve a psychological purpose, and occur in a psychological context in which they are understandable.”

What’s good for the goose. “the concepts and insights we apply to our patients apply equally to ourselves. The psychoanalytic sensibility draws no distinctions between the psychological principles that apply to patients and those that apply to psychotherapists.”

Let’s take another look at this using a different author. In the 2018 article, “The scientific standing of psychoanalysis,” Mark Solms summarizes the core scientific claims of psychoanalysis as follows.

Three core claims:

“The human infant is not a blank slate; like all other species, we are born with innate needs.”

“The main task of mental development is to learn how to meet our needs in the world.”

“Most of our action plans (i.e. ways of meeting our needs) are executed unconsciously.”

Clinical implications:

“Emotional disorders entail unsuccessful attempts to satisfy needs.”

“The main purpose of psychological treatment, then, is to help patients learn better (more effective) ways of meeting their needs.”

“Psychoanalytical therapy differs from other forms of psychotherapy in that it aims to change deeply automatized action plans.”

Outcomes:

Psychotherapy in general is an effective form of treatment.

“Psychoanalytic psychotherapy is equally effective as other forms of evidence-based psychotherapy.”

“The therapeutic techniques that predict the best treatment outcomes, regardless of the form of psychotherapy, make good sense in relation to the psychodynamic mechanisms outlined above.”

I want to say something about the falsifiability part of Bloom’s discussion. What Bloom misses is that psychoanalysis takes place in a clinical context. The core claims of psychoanalysis, as expressed above by Shedler and Solms, are well-supported by a large body of evidence in psychology and cognitive science, and although they can in principle be falsified, they aren’t easy to refute. In the setting of a psychotherapeutic relationship, the core claims provide a basis for developing idiographic hypotheses that apply to the person sitting in front of the psychotherapist, taking into account the psychological development and dynamics of that particular patient. It is also the case that hypotheses vary in the confidence we assign to them: hypotheses can, in the beginning, be mere suggestions, offered with very little conviction in them, and the confidence in them increases or decreases as a function of how well or poorly they explain clinical data in psychotherapy. In the clinical context, this testing and falsifiability takes place not via formal experiments but by considerations such as how well the hypothesis explains the person’s past psychological development, what other competing explanations exist and what their merits are, to what degree the explanation resonates with the patient, and how well the hypothesis explains subsequent observations that come up in the course of psychotherapy.

To go back to Bloom’s example, why would a competent psychoanalyst assert to a patient with conviction (based on a priori or random, on-the-go speculation), “the root of your problems is hatred of your father”? A hypothesis of this sort would require evidence to support it from clinical history and clinical observation. It would likely be endorsed in the beginning with a low degree of confidence. And the psychotherapist would ideally be receptive to verification or falsification based on what the patient says in response and what is observed subsequently in psychotherapy.

Psychotherapists can certainly be dogmatic about hypotheses,1 and they can hold on to them even when there is very little in the patient’s statements or behaviors to support them. But scientists can be dogmatic about hypotheses in research contexts just as easily. In research, such dogmatism comes to light relatively quickly, since science progresses through open scrutiny of the evidence and attempts at replication. Psychotherapy is a deeply private endeavor. Dogmatism in the psychotherapy context is not easy to discover and scrutinize. But this is also why the discipline encourages practices by which such detection and correction can take place: an insistence on the need for rigorous training, on-going forms of peer supervision even during independent practice, avenues for presenting and discussing cases, and scholarly avenues to scrutinize and develop the theoretical foundations of the discipline. It is through this form of error-correction that the discipline of psychoanalysis has evolved. Generations of psychoanalysts have criticized the psychoanalytic ideas proposed by Freud and his colleagues as inadequate explanations of patient experiences and clinician observations in psychotherapy.

Kristian Kemtrup writes in a Psychology Today blogpost:

“Imagine all of psychoanalysis, a field with over 100 years of history, as a very big tree with Freud as the very bottom of the trunk and recent books and papers as the outermost branches. Jung's work, for example, branches out so early and grows so far away that we can think of Jungian psychoanalysis as being a separate tree. The center of this psychoanalytic tree has a few big solid branches with many many smaller branches stemming out and intertwining. Those central branches are the work of psychoanalysts such as Melanie Klein, Donald Winnicott, Wilfred Bion, Anna Freud, Salvador Ferenczi, and many more. Their ideas are what is taught at present, more often than Freud's, at psychoanalytic institutes, often in a pluralistic way, focused on pragmatic ways to use psychoanalytic theory to improve clinical practice.”

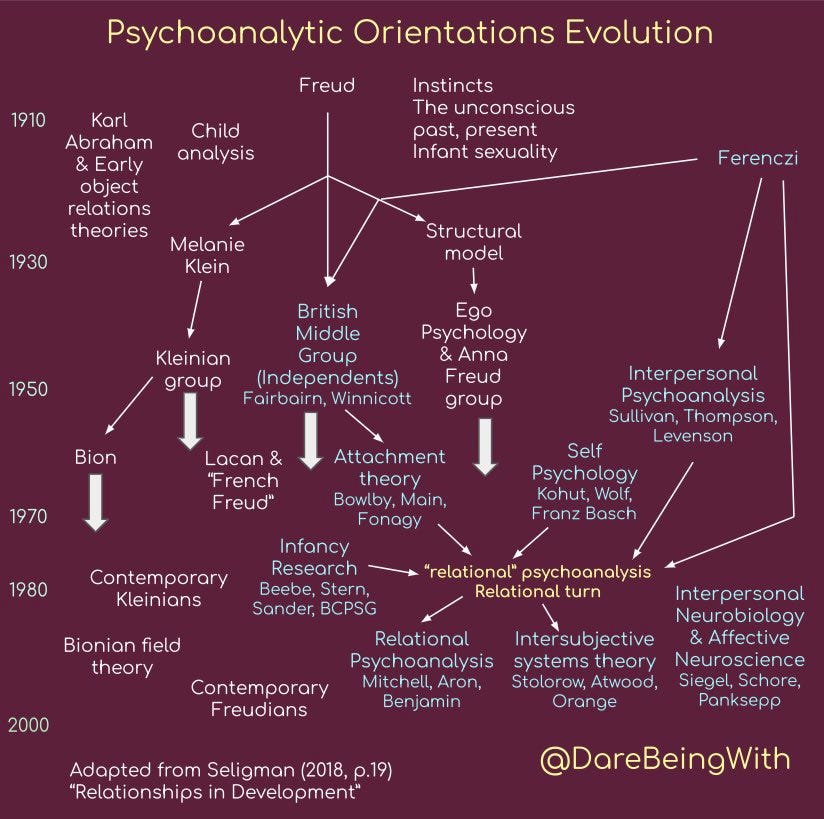

Jayce Long illustrates the evolution of psychoanalysis efficiently in this figure:

If we want to do justice to Freud’s legacy, we have to go beyond the man himself and explore this blossoming disciplinary tree that continues to intrigue and enchant psychiatrists, psychologists, and psy-clinicians, and that continues to be a source of insight and relief to countless people across the world, despite the fact that courses in psychology continue to portray all this as outdated and discredited. The fact that our scientific methods have not yet advanced enough for us to subject idiographic hypotheses to rigorous empirical testing is a shortcoming of our scientific methods, but it is not a sufficient reason for clinicians to abandon the endeavor.

See also:

Jonathan Shedler writes in the 2022 article:

“In the hands of a dogmatic, authoritarian, or unreflective therapist (attitudes that have no place in any form of psychotherapy), the concept of transference can be misused. In the worst-case scenario, it can become a way of blaming the patient for the therapist’s failings. For example, if a therapist treats a patient callously, it would be a travesty of psychoanalytic practice to interpret the patient’s hurt and anger as a pathological “transference” distortion. Contemporary psychoanalysts who advocate relational and intersubjective approaches remind us that our patient’s responses do not occur in a vacuum.”

“… there was a time in the history of psychanalysis when some practitioners adopted a distant stance and spoke as authorities on patients’ inner experience. I can, in good conscience, say nothing could be more antithetical to the spirit of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic therapy is not something done to or practiced on another person. It is something done with another person.”

You write a lovely summary of the good ideas that Freud popularized, but don’t mention the profoundly damaging ideas that he also popularized. The most famous was replacing his seduction theory with the Oedipal theory as written about by Jeffrey Masson in his book Assault on Truth and his 1984 Atlantic article: Freud and the Seduction Theory.

So I feel that your article is unbalanced—whitewashing even—and as someone who has been harmed by Freud’s ideas I feel a need to say something. He influenced therapists to deny incest, and more generally he deflected patients from focusing on any of the abuse inflicted on them by their families.

Consider the example you mention of the psychoanalyst saying to their patient “the root of your problems is hatred of your father.” This is the kind of psychic conflict that psychoanalysts are still focused on. They are not nearly so interested in what the father did to provoke the hatred.

They say they believe in repression, but they prefer to focus on the emotions and desires that are repressed rather than the memories of the abuse so many of us have suffered from fathers and other family members.

A fair and insightful piece. In my view, Freud’s great innovation was not to propose that there are mental processes outside of our waking knowledge and control (the early modern hierarchy of mental faculties, for example, is a similar concept), but to posit that these different versions of the self could be brought into dialogue in a therapeutic process. One simply can’t get around the immensity of this simple shift in thinking, whether in mental health or the broader culture.