Antipsychotic tapering appears to help long-term in a new trial but not for the obvious reason

And considerable uncertainty remains

Last year I published a review in Psychological Medicine (open access) examining what we know about antipsychotic medications and long-term functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. While antipsychotic medications clearly help with acute symptoms and preventing relapses in the first 1-2 years, the relationship between continuous medication use and long-term recovery is somewhat murky and subject to controversies. I argued that to make sense of the confusing literature and use it to guide clinical practice, we need to take two things seriously: natural history (the fact that psychotic disorders follow different trajectories in different people, with some recovering fully and others facing chronic illness) and personalization (the possibility that medication strategies that help one person may harm another).

The key point was that when we start with a heterogenous clinical cohort of psychotic patients, especially first-episode psychosis, the longer we follow them under non-randomized conditions, the more likely it is that differences in outcomes are attributable to differences in clinical course and selective retention of study subjects rather than the direct effect of medications. The evidence suggests that some people, perhaps around 20-30% of people with first-episode psychosis, do well with medication tapering and discontinuation over the long term, while the rest seem to benefit from continued treatment, but we do not know at the outset how things will turn out.

The HAMLETT study by Sommer et al., published in October 2025 in JAMA Psychiatry, was designed to provide us with more information regarding the long-term effects of early medication tapering in first-episode psychosis. The Dutch researchers recruited 347 people who had just recovered from their first episode of psychosis and randomly assigned them to either stop medication early (within the first year) or continue it for at least 12 months. They followed these patients for four years, measuring relapses as well as functioning and quality of life. Their sample included people with different diagnoses: chronic conditions like schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder alongside briefer conditions like schizophreniform disorder and brief psychotic disorder.

The authors concluded that while stopping medication early increases relapse risk in the first year, it leads to better long-term functioning. The use of antipsychotic medications was not significantly different between the two groups after the first year, after the randomization ended, suggesting that the continued use of antipsychotic medication itself cannot explain the difference, and the authors hypothesized that perhaps the “learning experience” of attempting discontinuation ultimately helps people manage their illness better.

This is a plausible conclusion, one I am quite tempted to accept, because I already believe in the importance of supporting patients with psychotic disorders who want to reduce or stop medications, and I’d like to think that collaborative opportunities to work together on careful dose reduction and discontinuation can indeed be valuable in enhancing patient agency and their comfort with medications. But, in terms of the study itself, there is some uncertainty in my mind about how to best interpret the reported results, and the clinical implications are certainly up for debate.

The Study Setup

The HAMLETT study recruited 347 people across 26 mental health centers in the Netherlands between 2017 and 2023. All participants had experienced their first episode of psychosis and had been stable on medication for 3-6 months.

The participants were split into two groups:

Dose Reduction/Discontinuation (DRD) group (168 people): Gradually reduced medication over about 3 months with the goal of stopping completely or reducing by at least 25%

Maintenance group (179 people): Continued their medication at the same dose, or reduced equal to or less than 25%, for at least one year.

Both groups were followed for four years, with assessments every few months initially, then annually.

The main outcome was something called the WHO-DAS-II score—a questionnaire where patients rate their own functioning in daily life.

They also measured:

Researcher-rated functioning (called the GAF score, where a clinician rates how well you’re doing)

Quality of life

Symptom severity

Relapse rates (return of psychosis)

Side effects like weight gain

How much medication people were actually taking

Participants had different specific diagnoses within the broad category of “first-episode psychosis”

45% had schizophrenia (typically a chronic condition)

23% had schizoaffective disorder (psychosis plus substantial mood symptoms)

27% had schizophreniform disorder (like schizophrenia but shorter, often less severe)

4% had brief psychotic disorder (very short episode, usually good prognosis)

The study was single-blinded. All the raters were blinded; participants and treating physician weren’t.

Study Results

In the first year, at the end of randomization phase of the study,

The DRD group had 2.84 times higher risk of relapse of psychosis

They reported worse quality of life

Three people in the DRD group died by suicide, compared to one in the maintenance group

In the long term, at the 3rd and 4th year marks:

The DRD group scored 6 points higher on the GAF (researcher-rated functioning)

Symptoms were non-significantly lower (lower PANSS score) in the DRD group

Medication doses were similar in both groups by this point

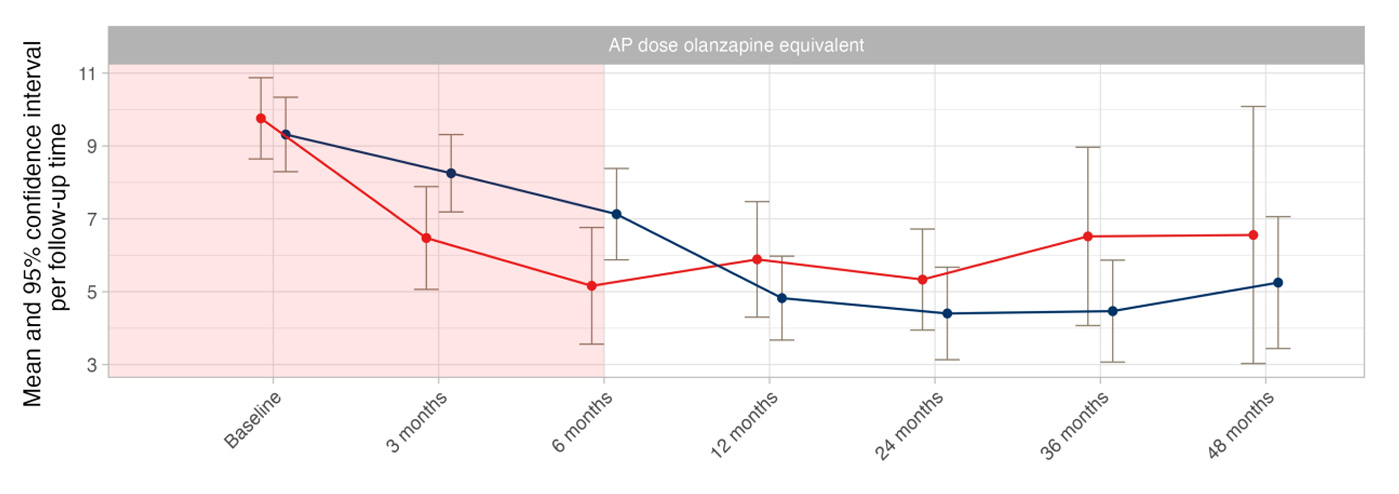

By 12 months, both groups were taking similar amounts of medication. You can see this in Figure G of the main article (above) and in Table 2 (page 4).

From 12 months to 48 months, there is no difference between those who were assigned to dose reduction/discontinuation and those who were assigned to maintenance. I agree with the authors that this makes it very unlikely that functional status at 48 months is due to the direct pharmacological effects of the medication dose reduction and discontinuation.

The authors propose that working with collaborative clinicians and experiencing the consequences teaches people to appreciate medication as a tool they can use to manage their mental health:

“Beneficial longer-term effects for the DRD condition cannot be attributed to direct effects of antipsychotic medication because doses were similar from 12 months onwards. Rather, a guided tapering attempt may strengthen therapeutic alliance and disease insight. Symptom return after guided DRD can help patients accept antipsychotic medication as a resource supporting mental stability, a crucial step in coping with psychotic vulnerability.”

Other Considerations

Primary Outcome: Patient-Rated Functioning

Remember how the primary outcome was the WHO-DAS-II score, where patients rate their own functioning? That measure showed no difference between the groups. Not at year 1, not at year 3, not at year 4. On the measure that patients themselves filled out about their own functioning, there was no long-term benefit.

The “better functioning” finding that the authors emphasize comes from the GAF, a score that is assigned by researchers to patients, not something patients reported themselves. The discrepancy between WHO-DAS and GAF suggests we need to be more cautious. Especially because the researchers weren’t blind to which group patients were in. (Edit: raters were blinded, but patients and physicians weren’t.)

Update: I’ve learned from the study team that the WHO-DAS-II outcome was chosen based on feedback from individuals with lived experience, as they regarded this as the most important outcome. However, some researchers on the team are of the view that it may possibly be less sensitive to change.

The Dropout Problem

Let’s look at how many people were actually assessed at each time point (from the CONSORT diagram in eAppendix 4, page 8 of Supplement 2):

DRD group (started with 168 people):

12 months: 134 assessed (80%)

36 months: 82 assessed (49%)

48 months: 44 assessed (26%)

Maintenance group (started with 179 people):

12 months: 128 assessed (72%)

36 months: 78 assessed (44%)

48 months: 54 assessed (30%)

At year 4, overall, only 98 out of 347 people (28%) were still being assessed. 72% of people dropped out before reaching the four-year mark.

The study’s main conclusion, that stopping medication early leads to better functioning at years 3-4, is based on roughly one-quarter of the people who started the study. Would these results still hold if there had been minimal dropouts?

[Update: I’ve been informed by a member of the study team that the 4-year follow-up numbers are low not only due to dropout, but also because the study is ongoing. HAMLETT has been increased to a 10-year follow-up, and at the time of this analysis not all participants had reached their 4th year within the study.]

The Two Analyses

The study analyzed the data in two different ways.

Intention-to-Treat (ITT) analysis: This analyzes people based on which group they were randomly assigned to, regardless of whether they actually followed the plan. If you were supposed to stop medication but decided to continue it, you’re still counted in the “stop medication” group.

Per-Protocol (PP) analysis: This analyzes people based on what they actually did. If you were supposed to stop medication but continued it, you get moved to the “continue medication” group for this analysis.

Usually, ITT is considered the “gold standard” because it preserves the benefits of randomization and reflects real-world practice (where people don’t always do what they’re supposed to).

40% of the maintenance group reduced their medication (from eAppendix 1, page 3 of Supplement 2). This massive crossover rate creates a problem: The “maintenance” group in the ITT analysis actually includes many people who stopped taking medication. This makes the maintenance group look worse than true maintenance would be.

To account for this, the researchers also did a per-protocol analysis, looking at people based on what they actually did (verified through pharmacy records).

From ITT (Table 2):

12 months: DRD had 2.84 times higher relapse risk (p = 0.04, statistically significant)

From Per-Protocol (Table 8A, page 15 of Supplement 2):

12 months: DRD had 1.62 times higher relapse risk (p = 0.34, NOT statistically significant)

From ITT:

Better functioning shows up at 36 and 48 months

From Per-Protocol:

Better functioning shows up at 6 months (much earlier)

The effect is stronger

There’s also improvement in symptoms (PANSS scores) from 6 months onward

So in the per-protocol analysis, stopping medication looks much better. Benefits appear earlier, are stronger, and there’s no relapse penalty.

There are two possible explanations:

Explanation 1 (which the authors favor): The per-protocol analysis shows the “true” effect of actually stopping vs. continuing medication. The ITT analysis is distorted by all those people in the maintenance group who stopped anyway.

Explanation 2 (which is also plausible): The per-protocol analysis is biased by selection effects. Who successfully stopped medication in the DRD group? Probably people whose illness and psychosocial characteristics allowed them to do so. Who violated the protocol and stopped medication in the maintenance group? Probably people who felt they didn’t need it and whose illness and psychosocial characteristics allowed them to do so.

The divergence between these analyses creates fundamental uncertainty. We don’t know:

If stopping medication actually helps (per-protocol suggests yes)

Or, if a subset of people with first-episode psychosis are simply more successful at stopping (selection bias), regardless of which group they are assigned to.

I lean toward the latter explanation.

Diagnostic Subgroups

The researchers did what they call a “sensitivity analysis,” looking just at the people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, the more chronic, severe conditions. This is in eAppendix 10 (pages 20-22 of Supplement 2).

Let’s compare the full sample to just the schizophrenia/schizoaffective patients:

Relapses:

Full sample (Table 2)

12 months: 2.84 times higher risk in DRD (p = 0.04)

24 months: 2.56 times higher risk (p = 0.06, just above the threshold for significance)

Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective only (Table 10B, page 21)

12 months: 3.24 times higher risk in DRD (p = 0.037)

24 months: 3.23 times higher risk (p = 0.035, still significant)

For people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, we can say with more confidence that the increased relapse risk lasted up to 24 months.

Functioning Benefits:

The GAF benefit is slightly smaller at 48 months but overall comparable for people with chronic psychosis (5.62 points better on GAF for schizophrenia/schizoaffective vs 6.13 points in the full sample)

Medication Dose:

The DRD group started with a dose of 9.76 mg, successfully reduced antipsychotic dose (in mg of olanzapine-equivalent) to 5.16 mg at 6 months and 5.89 mg at 12 months, but was on 6.56 mg. This is a total reduction from baseline of 33%. The maintenance group started similarly at 9.32 mg, experienced a major dose reduction, even more than the DRD group (indicating that people were discontinuing even without clinical support), reaching 4.82 mg at 12 months, and was at 5.11 mg at 48 months. A total reduction from baseline of 45%. (Table 10A, page 20)

The maintenance group ended up on lower doses than the DRD group! The difference is not statistically significant, but still…

Relapses

The study reports that stopping medication early increased the risk of relapse. This is the main short-term harm. But we know almost nothing about what happened to the people who relapsed. What happened after the ~40 people who relapsed? Did they recover fully? Did they get back to their previous level of functioning? What medication dose was needed to restabilize? Where are they in year 4?

What Can We Actually Conclude?

We can say with high confidence that under randomized conditions, dose reduction and discontinuation increase the risk of relapse, with worse quality of life, and a signal for an increase in suicides. When patients are followed over 3-4 years, beyond the period of randomization, the patients who attempted dose reduction and discontinuation went back on antipsychotics with dosages that are similar to or slightly higher than their counterparts.

We see better researcher-rated functioning compared to people in the maintenance arm, but no difference in patient-rated functioning. The superiority on the GAF scale at year 4 is based on only 28% of the original sample (massive dropout). This reduces our confidence in the validity of the long-term functioning benefit finding. Possible explanations of the GAF difference could be:

A real benefit from the “learning experience” (authors’ interpretation)

Benefit from direct but delayed pharmacological effect of reduced exposure to antipsychotics (possible, but unlikely)

Researcher bias (unblinded assessors expected to find benefits)(edit: raters were blinded)Selection effects

Statistical fluke (massive dropouts, multiple comparisons)

Diagnostic heterogeneity (finding may be more applicable to mild cases or a diagnostic subset)

My Takeaway

I previously wrote in my discussion of the RADAR trial, “RADAR Trial: A Reality Check for Critics of Antipsychotics” (2023)

“… it is possible that early dose reduction may confer benefits many years later, but given the observational nature of the second phase of follow-up and the methodological problems that exist in such studies, it is difficult to say with high confidence. The RADAR team is planning for a follow-up observational phase similar to Wunderink et al. However, even if they replicate the finding by Wunderink et al. (and replication is not guaranteed), it is not likely to have much clinical force. We have solid evidence from randomized data that over a 2-year period, antipsychotic dose reduction or discontinuation nearly doubles the risk of relapse without improving functioning (for the average patient); clinicians will reasonably give this finding more weight compared to a finding that non-conclusively suggests possible benefits in functioning 7 years later.”

“… findings from the RADAR trial still leave a lot of room for personalization of care. There are many situations where antipsychotic dose reduction and discontinuation are clinically appropriate, and patients should be empowered to make these decisions whenever possible. For those maintained on medications, the goal should be a medication and dose that they tolerate well. Qualitative data from some subjects in the RADAR trial showed that many patients found the collaborative process to be helpful and “developed novel perspectives on medication, dose optimisation, and how to manage their mental health. Others were more ambivalent about reduction or experienced less overall impact.”

I had also pointed out in my discussion of the RADAR trial in the Psychological Medicine paper:

“34 (27%) of those randomized to reduction stopped their antipsychotic medication completely at some time during the 24-month follow-up period. By 24 months, only 13 people (10%) in the reduction group were not taking antipsychotics. That is, out of the 34 who stopped their antipsychotics completely at some point, 62% had to resume taking antipsychotics. This illustrates the difficulty posed by antipsychotic discontinuation in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Even in a trial where discontinuation was permitted and encouraged as a goal, only a fraction was able to stop their antipsychotics and stay off them. Successful dose reduction is often a more realistic outcome in the clinic than successful discontinuation.”

I think HAMLETT demonstrates that same thing. Even when a trial was designed to provide people a supportive environment to reduce or discontinue their antipsychotic medications, people who were assigned to reducing or stopping their medications subsequently had to resume antipsychotics or increase doses, such that over 3-4 years they were on comparable doses (if not higher) to people who had been assigned to the maintenance group.

Successful, sustained antipsychotic discontinuation is difficult. A minority achieves it, no doubt, but it is not a realistic goal we can set for most people with schizophrenia.

I believe that antipsychotic medications genuinely reduce the risk of relapse of psychosis in schizophrenia spectrum disorders over both the short term and the long term. We see it robustly under randomized conditions, and the effects begin to wear off, tellingly, only after randomization has ended. A subset of patients with psychotic disorders successfully discontinue antipsychotics and do well without them. I am also of the view that for some people antipsychotics generally cause so many side effects that it is better for them to manage psychotic symptoms via psychosocial interventions. I am also willing to accept that dose reduction/discontinuation may confer functional benefits down the road for some people, whether through improved learning/insight or through some other mechanism, but I remain uncertain at the moment about whether this is truly the case (and even if it is true, it has to be balanced against the risk of increased relapse).

The sensible conclusion in light of all this is that treatment should be collaborative and personalized. Currently, many clinicians err on the side of keeping everyone on medication long-term to prevent relapse, or resist reducing their dose substantially, even when patients experience significant side effects like feeling mentally dull, sedated, or feel that medications are reducing their quality of life. This approach, while well-intentioned, can harm patients who would do better with lower doses or no medication. At the same time, the idea that we should encourage everyone to taper and stop antipsychotic medications is even more misguided. In the end, there is no substitute for individualized, collaborative care that takes into account each person’s symptomatology, illness course, side-effect burden, preferences, and support system, and allows people “the dignity of risk taking.”

[Comments are open]

I agree with your measured thoughts. My anecdote from the last couple years: I have been the psychiatric provider for an intensive outpatient dual diagnosis program where all of the patients have significant substance use disorders and most of the patients have thought disorders and were recently discharged from the Oregon State Hospital (OSH). I find (especially compared to the population I work with at a secured residential treatment facility that treats mostly patients with schizophrenia who lack the SUD component) that this dual diagnosis population has a lot more success coming off medication than the average patient with schizophrenia. This level of diagnostic nuance will probably never be captured well by these kinds of studies, so I am fully with you on the clinical decision-making and collaboration that goes into this kind of individualized/personalized care.

A sizable number of people leaving the study group is perhaps unavoidable, but only having a quarter of the original group in the final analysis seems enough, to me, to throw all of the conclusions immediately into question.

However, as a layman, I’m obviously underequipped to be confident in that interpretation.

Are these sort of dropout rates typical? Has reliance on studies with similar dropout rates led to (in the main) better clinical outcomes over time? Especially in the case of psychotic disorders, are these rates just something you have to live with, given the decreasing number of long-term care facilities that could ensure more continuous monitoring over an extended period of time?