Can We Please Stop Bullshitting Patients With Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction?

This post is a follow-up to:

I often think that the way we approach rare and disabling but poorly understood adverse effects of medical interventions tells us a lot about the priorities of the medical community and who it really serves. If you have the misfortune of experiencing such iatrogenic harm, you are likely to have the further misfortune of being dismissed or disbelieved by medical providers.

Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction (PSSD) is one such condition. A 2019 study by Healy et al. on patient experiences of engagement with healthcare professionals about PSSD reported:

“While some had received support and validation of their condition, many described a number of difficulties including a lack of awareness or knowledge about PSSD, not being listened to, receiving unsympathetic or inappropriate responses, and a refusal to engage with the published medical literature.”

Healy writes in another article, “… in addition to the direct treatment harms, many patients [experiencing PSSD] are harmed by the response of their doctors. They are ridiculed for thinking a drug could cause a problem after it leaves the body.”

I was reminded of all this by a story on PSSD from November 2023 in the New York Times. The story features these jarring comments from Dr. Anita Clayton:

“I think it’s depression recurring. Until proven otherwise, that’s what it is,” said Dr. Anita Clayton, the chief of psychiatry at the University of Virginia School of Medicine and a leader of an expert group that will meet in Spain next year to formally define the condition.

Dr. Clayton published some of the earliest research showing that S.S.R.I.s come with widespread sexual side effects. She said patients with these problems should talk to their doctors about switching to a different antidepressant or a combination of drugs.

She worries that too much attention on seemingly rare cases of sexual dysfunction after S.S.R.I.s are stopped could dissuade suicidal patients from trying the medications. “I have a really big fear about this,” she said.

To say that persisting sexual dysfunction after SSRI use is “depression recurring until proven otherwise” is a thinly veiled denial of the existence of the very condition. It is obvious to anyone clinically and scientifically interested in this issue that depression is an important possibility for differential diagnosis to consider and exclude. Depression does negatively influence sexual functioning and shares some symptoms with PSSD, but the cases that have been reported as PSSD in the published literature are cases where depression has been considered and has been found wanting as the explanation.

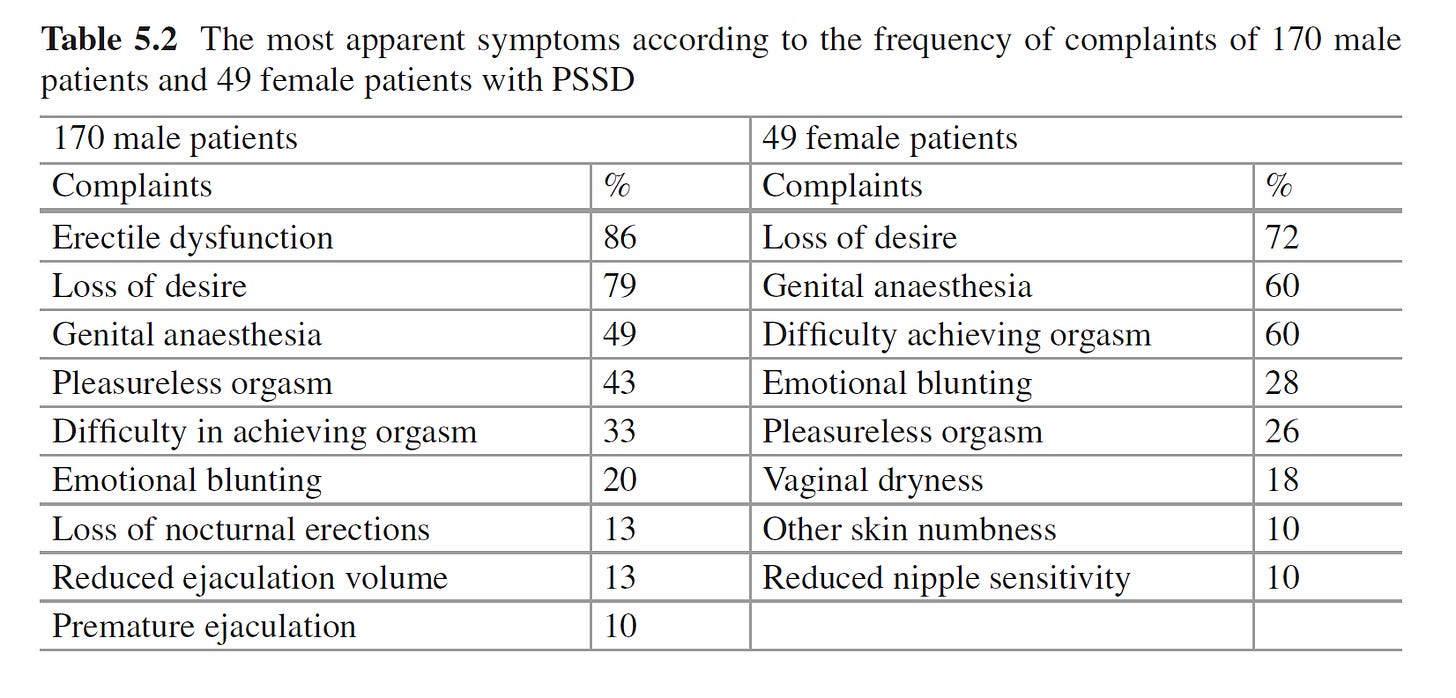

Consider sexual adverse effects during SSRI treatment. They are common, they can often be quite severe, and their existence is firmly established. As the New York Times notes, Dr. Clayton’s own research helped establish this. Her 2002 paper reported that SSRIs and SNRIs were associated with high rates of sexual dysfunction, 36-43% among overall users, with a range of 7-30% among those who didn’t have predisposing factors for sexual dysfunction. The medical resource UpToDate says that “the best estimate is that sexual impairment occurs in roughly 50 percent of patients treated with SSRIs.” The most common symptoms are low libido (low sexual desire), difficulty achieving orgasm (anorgasmia), and erectile dysfunction. All three symptoms can also be experienced in untreated depression. So how can we be sure that these symptoms are caused by SSRIs? Well, we have randomized placebo-controlled trials that show that these adverse effects are experienced by depressed patients receiving SSRIs at a much higher rate than those receiving placebo. But in the clinic, in the case of any particular patient, we cannot rely on RCTs. We have to rely on old-fashioned clinical detective work. Did the person experience sexual dysfunction when they were depressed and untreated, or did the dysfunction start only after treatment was started? Is the severity of dysfunction dose-related? If the patient did have depressed-related sexual dysfunction prior to treatment, have they now experienced a change in the quality of the dysfunction that is different from before? Are they experiencing symptoms (e.g., genital anesthesia) that are unusual manifestations of depression? Are there other concomitant factors that could explain this better? Etc.

Imagine that these are the early days of our knowledge of these issues, and patients experiencing sexual adverse effects of SSRIs are trying to raise awareness and attract medical attention. A prominent psychiatrist confidently makes a public statement in response to these efforts: “Any sexual dysfunction arising during SSRI treatment is a symptom of depression until proven otherwise. I am really worried that depressed patients are not going to start antidepressants out of fear of sexual dysfunction.” We would be correct to infer that this psychiatrist is skeptical that SSRIs cause sexual dysfunction during treatment and seems to think that depression-related sexual dysfunction is being misdiagnosed as SSRI-related sexual dysfunction, and that this psychiatrist prioritizes getting patients to take a treatment over considerations of iatrogenic harm. This is precisely the same dynamic when the patients suffering from PSSD are told, “This is depression recurring unless proven otherwise.” Is it so hard to believe that sexual dysfunction that occurs with treatment can persist after discontinuation under uncommon circumstances?

Alright, how can we prove otherwise? It depends on what standard of evidence we insist on. RCTs cannot settle the issue of rare adverse effects. For example, RCTs cannot be used to determine whether antipsychotics cause torsade de pointes because it is incredibly rare. I do know that the medical community at times responds even to common adverse effects with denial or minimization. (In 2006, the maker of Zyprexa, Eli Lilly, told the New York Times: “In summary, there is no scientific evidence establishing that Zyprexa causes diabetes.”)

We have to apply reasonable standards of causal inference. Genital anesthesia, for example, is exceedingly unlikely to be due to depression. And it would be highly unusual for genital anesthesia to emerge shortly after an SSRI was initiated if it were due to depression. Let’s consider the most straightforward PSSD scenario: A depressed person starts treatment with SSRI and experiences genital anesthesia, anorgasmia, and low libido. There is little doubt at this point, while they are still receiving the SSRI, that this is because of the SSRI. Now let’s say that the person discontinues the SSRI, but the sexual dysfunction persists. It’s been 6 months since discontinuation, but the dysfunction has not gone away. The person’s depressive symptoms have waxed and waned in intensity, but there has been no change in sexual dysfunction. The person has never experienced anything like this with depression in the past. There is no other obvious explanation, and a medical workup for sexual dysfunction reveals no other causes. The clinician recommends trying Wellbutrin, which the patient reluctantly tries. The mood improves, but sexual dysfunction continues. Any clinician applying reasonable standards of inference would not attribute this sexual dysfunction to depression and would consider the SSRI to be a likely culprit. Someone more skeptically minded might say, “I don’t know what is causing this. I am uncertain if the SSRI caused this. It has not been scientifically established that SSRIs can cause persistent sexual dysfunction, so I can’t say for sure.” I respect that. I do. There is also room for some degree of skepticism because there are cases that are atypical even by standards of medication-induced sexual dysfunction; these are cases where permanent genital anesthesia happens with just one or two doses, or cases where sexual dysfunction happens after discontinuation rather than during treatment. I respect an open-minded critical approach, especially when it comes to atypical cases, but what I do not respect is a dogmatic “This is depression until proven otherwise” stance that closes off possibilities before they are even properly explored. Such a stance approaches an uncertain situation full of unknowns with a prior belief to which extremely high confidence has been assigned.

I respect an open-minded critical approach, especially when it comes to atypical cases, but what I do not respect is a dogmatic “This is depression until proven otherwise” stance that closes off possibilities before they are even properly explored. Such a stance approaches an uncertain situation full of unknowns with a prior belief to which extremely high confidence has been assigned.

I previously said about medically unexplained symptoms during my discussion with Diane O’Leary:

The problem in the case of “medically unexplained symptoms” is that clinicians end up offering bad explanations of psychosocial causes (“it’s stress”) or they misdiagnose the problem as a psychiatric disorder (as depressive disorder or as anxiety disorder, which may very well be comorbid but are not the correct diagnosis for the complaint). And this basically conveys the implicit message that the problem is “all in one’s head” and becomes a powerful form of dismissal, invalidation, and neglect.

This is all compounded by the inability of current healthcare professionals and systems to patiently work with unexplained symptoms and provide adequate care. Brian Teare has written about the experience of remaining undiagnosed after a series of medical tests: “I was betrayed by my own GP. She didn’t say the phrase It’s all in your head, but she might as well have... I keep imagining what it would have meant to have encountered a doctor who said, I’m at the end of the care I can give you, and though I couldn’t diagnose your illness, I believe you are ill and you need more comprehensive testing than public health can provide.”

I implore my fellow clinicians to approach cases such as PSSD with more sensitivity and to stop saying things that are the equivalent of “it’s all in your head.” The very least we should offer is an honest acknowledgment:

“Although I do not know what the cause is or what the nature of the relationship between your sexual dysfunction and SSRI use is, I believe your sexual dysfunction is real, that you are deserving of care, that from your perspective it is reasonable to believe that the medication is responsible, and I am open to the possibility that the medication may have caused this, perhaps in combination with other risk factors we haven’t yet identified. Let’s work together to figure out what we can about this problem until I am at the end of the care I can give you. And when I am at the end of the care I can give you, I will not abandon you. I will still advocate for you so that this condition can be studied and better understood by us all, and so that others in the future do not have to suffer as you are suffering.”

It's bizarre how mental health professionals can, simultaneously, hold these two beliefs:

1. Psych patients tend to be a suspicious lot

2. We shouldn't be too honest with psych patients. It's better to sugarcoat things or just not mention inconvenient truths, otherwise we might scare them away.

#notallclinicians, and obviously not you, but it's common enough. Better not talk to patients about potential bad side effects of their meds. Better not tell suicidal people that "reaching out" might land them in coercive care. Better not say this, better not say that, because it might scare people away from treatment.

Guess what OFTEN scares people away from treatment? This precise attitude! Psych patients aren't isolated islands. We talk to each other, both afk and online (you know the internet? It's a thing! It's been a thing for a long time now!) It's impossible to conceal inconvenient truths from psych patients by refusing to talk about them. But it IS possible to spread the view that psych docs are unreliable bastards who will lie and deceive and say anything to trick you into treatment.

Sure, people can be paranoid of psych docs regardless - I had some serious psych doc paranoia myself, way back in the distant time of 1993, before I had even touched the internet OR become friends with any other psych patients. But the above attitude does nothing but INCREASE the problem of patients not trusting clinicians.

Excellent piece. Thank you.