Do all roads lead to mitochondria?

Palmer's "Brain Energy" makes a compelling case for the importance of metabolism in psychiatry but falls short of a unifying theory

If you are active on social media or listen to podcasts, you’ve likely come across the latest “hot take” that mental disorders are metabolic disorders of the brain. The passionate advocate of this position is the psychiatrist Christopher Palmer, who is Director of the Department of Postgraduate and Continuing Education at McLean Hospital, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, and author of the 2022 book “Brain Energy: A Revolutionary Breakthrough in Understanding Mental Health—and Improving Treatment for Anxiety, Depression, OCD, PTSD, and More.” The book makes numerous bold claims, and promises the readers a “revolutionary new understanding that for the first time unites our existing knowledge about mental illness within a single framework.” It starts with Palmer describing the case of a person with chronic, treatment-resistant psychosis who unexpectedly shows tremendous symptomatic and functional improvement with the keto diet, leading Palmer onto a journey culminating in this book.

Although I have many issues with the book, I enjoyed reading it. I learned a lot about research around metabolism and mitochondria that I wasn’t quite familiar with, and I gained a new appreciation of the metabolic dimension of psychiatry. Palmer is clearly knowledgeable, has devoted considerable effort to the project, and if the anecdotes in the book are anything to go by, is a very caring and skilled clinician. I found something of value in how Palmer conceptualized the problems and approached the treatment of his patients. I also thought that Palmer’s critique of DSM-style categorical thinking in psychiatry was articulated quite well. The book inspired me to look at some of the scientific literature on mitochondrial dysfunction in psychiatry myself. For interested readers, I’ll suggest this exchange in JAMA Psychiatry (here, here, here) and a special issue of Biological Psychiatry on “Mitochondrial Dynamics and Bioenergetics in Psychiatry” as starting points.

So what’s my beef with Brain Energy? My grievances are fundamentally around the conceptualization of mental disorders as metabolic disorders and the explanatory reduction of psychopathology to mitochondrial dysregulation. I’m sensitive to assertions that take the form “mental disorders are XYZ,” having devoted considerable time and energy to the “mental disorders are brain disorders” debate and to issues around explanatory reductionism. So I approach the assertion, “mental disorders are metabolic disorders” with insights that I have gleaned from my prior theoretical work. Furthermore, I am in the Kendlerian camp of multi-factorial, multi-level complexity that generally rejects the idea of a single common pathway onto which all the causal factors relevant to psychopathology converge. In other words, I hold the sort of view that Palmer wishes to disprove, and I do not find his case to be persuasive.

It is important for me to acknowledge that I do generally accept the following:

Mitochondrial dysfunction appears to be an important risk factor for psychopathology

Metabolic pathways appear to be important mechanisms involved in psychopathology

Interventions that seek to modify metabolism — such as dietary changes — appear to be effective strategies for a subset of patients with psychiatric disorders.

Metabolism appears to be an important pathway that explains the comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and various other medical disorders.

OK, now let’s take a look at some of the things I disagree with. In case anyone thinks I am criticizing a hyperbolic strawman, I’ll quote directly from Brain Energy to make my points!

The central claim of the book:

“Mental disorders— all of them— are metabolic disorders of the brain.”

Palmer sees his theory as a unifying explanation for etiology and treatment:

“When I finally put all the pieces together, I realized that I had stumbled upon something beyond my wildest dreams. I had developed a unifying theory for the cause of all mental illnesses. I call it the theory of brain energy.”

“I’ll show you that all the known contributing factors to mental illness, including things like genetics, inflammation, neurotransmitters, hormones, sleep, alcohol and drugs, love, heartbreak, meaning and purpose in life, trauma, and loneliness, can be tied directly to effects on metabolism and mitochondria.”

“All the symptoms of mental disorders can be tied directly to metabolism, or more specifically, mitochondria, which are the master regulators of metabolism.”

“All current treatments in the mental health field, including biological, psychological, and social interventions, likely work by affecting metabolism.”

Anyone attuned to the cognitive and psychodynamic complexities involved in psychotherapy will understandably bristle at the reductive suggestion that it is not simply the case that psychotherapies affect metabolism, but that it is by affecting metabolism that they work!

As Palmer elaborates on his ideas, it becomes clear that he takes a very broad approach to characterizing problems as metabolic problems. For instance, seizures, heart attacks, and strokes all become metabolic problems.

“Sometimes metabolic problems are acute, meaning that they are abrupt and dramatic. These can take the form of a heart attack, a stroke, or even death. A heart attack, for example, is usually due to a blood clot in one of the arteries feeding the heart. Some of the heart cells stop getting enough blood and oxygen. This prevents them from producing enough energy. If blood flow isn’t restored quickly, the heart cells die. This is a metabolic crisis in the heart. A stroke is an acute metabolic crisis in the brain. The ultimate metabolic crisis is death itself…”

This, to me, suggests a problematic conflation of disorders of metabolism — where aberrations of metabolic pathways are the primary problem — with disorders that involve or impact metabolism in some form or fashion (I struggle to think of a disorder that wouldn’t fall in this latter category!).

There are points at which Palmer himself seems aware of the worry, but he is quick to brush it away with claims of explanatory unification:

“In a way, of course mental disorders are related to metabolism. In essence, everything is! So what? What I’ll show in the coming chapters is that metabolism is, in fact, the only way to connect the dots of mental illness. It is the lowest common denominator for all mental disorders, all of the risk factors for mental disorders, and even all of the treatments that are currently used. And, perhaps most significantly, although metabolism is complex, solving metabolic problems is usually possible, oftentimes through straightforward interventions.”

“At first glance, they may think that the theory of brain energy offers nothing new. “Obviously mental disorders are related to metabolism! We’ve known that all along! Metabolism is everything in biology. What’s new here?” As I hope you’ll come to understand, there is something new here. And not just new, but revolutionary. While these researchers have been lost in the overwhelming complexity of metabolism and how the brain works, trying to figure out what is making some brain regions overactive and other brain regions underactive, they have failed to see the big picture of metabolism. Most importantly, they have failed to see the role of mitochondria in all of it. By stepping back and looking at the bigger picture (even if that bigger picture is playing out on a microscopic level), we can find new ways to understand what’s happening with metabolism and mental health and see new ways to address these problems.”

But the promise of explanatory unification is never delivered. Associations of various sorts are assumed to be causal without justification. The fact that individuals with mitochondrial diseases can exhibit a wide range of psychiatric symptoms is taken to erroneously imply that mitochondrial dysfunction must thereby be implicated in psychiatric disorders as well. For example:

“What these researchers failed to consider is how many other roles mitochondria play in cells apart from the production of energy. They also failed to recognize just how many different factors affect the function and health of mitochondria. When mitochondria don’t function properly, neither does the brain. When brain metabolism is not properly controlled, the brain doesn’t work properly. Symptoms can be highly variable, but mitochondrial dysfunction is both necessary and sufficient to explain all the symptoms of mental illness.”

Sure, when mitochondria don’t function properly, likely neither will the brain, but that doesn’t mean that when the brain doesn’t function properly, it must be because of mitochondrial dysfunction.

Since scientific studies show associations between psychiatric disorders and mitochondrial dysfunction, but do not demonstrate mitochondrial dysfunction (e.g. mutations of mitochondrial DNA, reduced numbers of mitochondria, or structural aberrations) in every instance of mental illness, Palmer has to invoke a broader concept of “mitochondrial dysregulation” to justify his claim that all mental illness is a metabolic problem.

“The more important cause of mitochondrial impairment is one that I’ll call mitochondrial dysregulation. Many of the factors that affect mitochondrial function come from outside the cell. They include neurotransmitters, hormones, peptides, inflammatory signals, and even something like alcohol. Yep! Alcohol affects the function of mitochondria. I refer to this as dysregulation, as opposed to dysfunction, because in some cases, the mitochondria were functioning just fine, but their environment became hostile quickly and caused impairment— similar to people doing the best they can when they are highly stressed.”

The notion of mitochondrial dysregulation ensures that even in the absence of demonstrable mitochondrial abnormalities, Palmer can keep his explanatory focus on mitochondria. The reliance on mitochondrial dysregulation is taken to absurd lengths. For example, consider psychedelics. If a person hallucinates because they have ingested LSD, in what sense is this fundamentally a metabolic problem? According to Palmer, the hallucinogen causes mitochondrial dysregulation, and this metabolic dysregulation is then responsible for the hallucinations.

“To give an easy example, a woman could be metabolically healthy, but if she takes a hallucinogen, she might begin to hallucinate right away. The drug dysregulates her metabolism and mitochondria, causing symptoms…”

I’m sure there are changes in brain metabolism taking place during substance-induced hallucinations, but the idea that we should give mitochondrial changes explanatory precedence over other hypothesized mechanisms by which psychedelics produce their effects (as just one example, “psychedelics work to relax the precision of high-level priors or beliefs, thereby liberating bottom-up information flow”) strikes me as problematically reductive. This privileging of the metabolic also runs counter to my own sympathies towards understanding psychopharmacology through the lens of explanatory pluralism.

Palmer does acknowledge that there is room for complexity, that there isn’t a simple, linear mediation via metabolic dysregulation:

“When it comes to metabolism and mitochondria, almost all things are regulated in a feedback loop.”

But this typically only serves as a basis for more speculative involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction in the etiology of various disorders:

“We know the more beta-amyloid that is present, the more likely it is that someone will develop Alzheimer’s disease. We also know it is toxic to mitochondria and causes mitochondrial dysfunction… What they have missed, however, is that mitochondrial dysfunction might very well be the cause of the accumulation of beta-amyloid itself.”

To illustrate the leaps of inference sprinkled throughout the book, consider:

“If a neuron has defects in its myelin coating, it will require more energy to work. An extreme example of this is multiple sclerosis, in which myelin is destroyed by an autoimmune process. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been associated with problems in myelin production and maintenance. Consistent with the brain energy theory, defects in myelin have been identified in the brains of people with schizophrenia, major depression, bipolar disorder, alcoholism, epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and even obesity.”

The argument is basically: Myelin defects interfere with metabolism, and mitochondrial dysfunction can also cause myelin defects, therefore, the association of myelin defects with various neuropsychiatric disorders is indirect evidence that these are also metabolic disorders! Such logical leaps are the glue holding the theory of brain energy together.

Another example:

“In some cases, people will describe “leaden paralysis,” a situation in which they feel like their arms and legs are made of lead and it’s difficult to even move them. Mitochondrial dysfunction in their muscles might explain this. If their muscles don’t have enough energy, people will have difficulty moving them. Catatonia is an extreme version of metabolic failure— people can appear paralyzed from their illness and have severe difficulty moving or speaking.”

In a particularly odd section of the book, Palmer argues that since every psychiatric symptom can be seen in delirium, we should conceptualize all mental illnesses as forms of delirium, and we should conceptualize delirium as mitochondrial dysfunction.

In a particularly odd section of the book, Palmer argues that since every psychiatric symptom can be seen in delirium, we should conceptualize all mental illnesses as forms of delirium, and we should conceptualize delirium as mitochondrial dysfunction. I kid you not! Read for yourself:

“One simple model would be to call all mental disorders delirium. Maybe we separate transient delirium and chronic delirium. The transient type resolves within two to three months, and the chronic type lasts longer. This label would remind all clinicians that they need to keep looking for the cause or causes of the metabolic brain dysfunction instead of simply administering symptomatic treatments. This would largely follow current treatment protocols for delirium already in place, but it would expand these protocols to all who are currently labeled “mentally ill.”

As some will resist the use of “delirium” for all mental disorders, we could, alternatively, call all mental disorders “metabolic brain dysfunction” and add specifiers for the different symptoms that people are experiencing. For example, someone with prominent anxiety symptoms might receive the diagnosis of “metabolic brain dysfunction with anxiety symptoms.” A person with schizophrenia might receive the diagnosis of “metabolic brain dysfunction with psychotic, depressive, and cognitive symptoms.” In all cases, the primary diagnosis would remain the same, “metabolic brain dysfunction,” but the symptoms would change as treatments work or as the illness progresses or remits.”

Eiko Fried and Donald Robinaugh write in an editorial about embracing complexity in mental health research:

“if we are to make genuine progress in explaining, predicting, and treating mental illness, we must study the systems from which psychopathology emerges… the systems that give rise to psychopathology encompass a host of components across biological, psychological, and social levels of analysis, intertwined in a web of complex interactions.”

In the article “How not to think about biomarkers in psychiatry” (co-authored with Manu Sharma), I use the example of chronic stress to make a broader point about biomarkers being embedded in complex causal webs:

“Chronic stress is another example where no explanatory reduction to the biological level alone is possible. This is because chronic stress emerges from the complex interaction between psychological agency, social task demands and social resources, and biological fight-flight-fright arousal systems. As Bolton and Gillett put it, “chronic stress as the key hypothesized mechanism linking psychosocial factors with poor physical and mental health outcomes is—as to be expected—a mechanism that explicitly addresses criss-crossing biological, psychological and social processes” [8]. Any biomarker of chronic stress would necessarily exist in the web of top-down and bottom-up causal influences.”

Mitochondrial function in psychopathology necessarily exists in a complex web of top-down and bottom-up causal interactions. When mitochondrial dysfunction is present (for instance, in mitochondrial diseases), it can indeed influence this causal web to such a degree that states of psychopathology can emerge. In many instances of psychopathology (as well as many other neuropsychiatric and metabolic disorders generally), we can zoom in on mitochondria and see some form of “mitochondrial dysregulation,” but it would be a mistake to think that mitochondrial function is necessarily the best way to explain the etiology and approach the treatment. In some conditions, in some stages of illness, in some individuals, and with some interventions, focusing on mitochondrial function may very well be the best approach, and it is a worthwhile research agenda to figure out what those situations may be, but focusing on mitochondrial function as a fundamental mechanism of psychopathology across the board will not be meaningful, either clinically or scientifically.

Mitochondrial function in psychopathology necessarily exists in a complex web of top-down and bottom-up causal interactions… we can zoom in on mitochondria and see some form of “mitochondrial dysregulation,” but it would be a mistake to think that mitochondrial function is the best way to explain the etiology and approach the treatment of the condition. In some conditions, in some stages of illness, in some individuals, and with some interventions, focusing on mitochondrial function may very well be the best approach, and it is a worthwhile research agenda to figure out what those situations may be, but focusing on mitochondrial function as a fundamental mechanism of psychopathology across the board will not be meaningful, either clinically or scientifically.

Here’s how Palmer seems to understand the relationship between causal risk factors and mitochondrial function:

Here’s how I think it is likely to be:

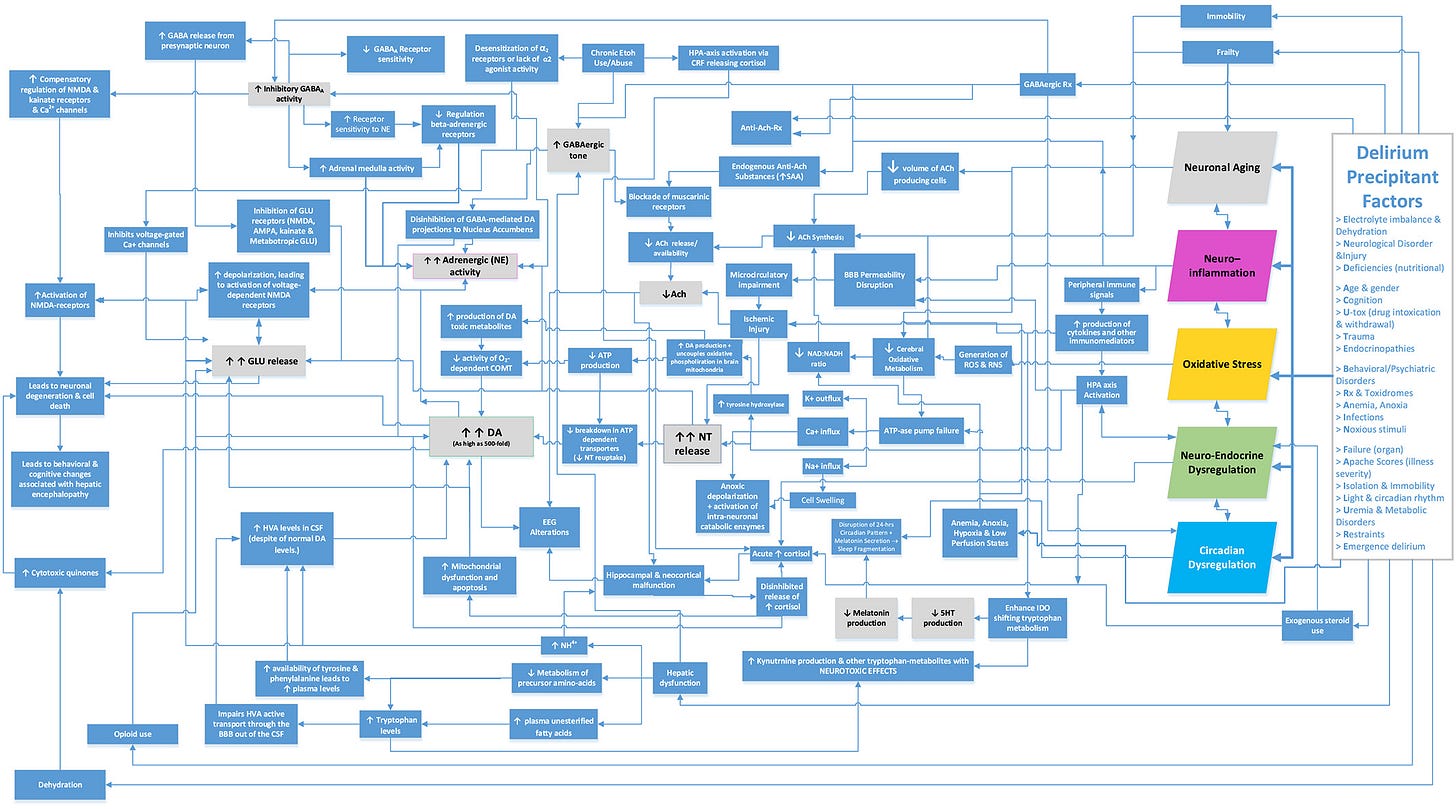

Since Palmer uses the example of delirium, we can take a look at delirium. This is how José R. Maldonado, one of the world’s leading experts on the subject, understands the pathophysiology of delirium:

If you are wondering whether mitochondria are in there somewhere in the figure, yes, they are, but in a very unprivileged position in the causal web, as we would expect:

Metabolic pathways and psychological processes have an organizational relationship. Mitochondrial function exists within multiple “layers” of regulatory control mechanisms. Mechanisms that, for instance, control the distribution of glucose and hence its availability at the cellular level. Or, mechanisms that coordinate the activity of organs, such as the heart and the gut, and determine their hyper or hypo activity. Or, mechanisms that control the interaction of the organism with the environment, recognize potential threats, and activate fight or flight behaviors. Etc. Humans are embedded in even more complex forms of social regulation, where social and political forms of organization determine what sort of nutritional resources an individual has access to, what sort of environmental threats they are subject to, and ultimately, how much glucose is available to the mitochondria within the cells of an individual. Every regulatory control mechanism comes with its own form of dysregulation, and the regulatory control mechanisms exist in a complex web of interactions with both upward and downward causation. There is no way to bypass this complexity by focusing on mitochondria as the lowest common denominator.

There is yet another factor that drives my criticism. I see psychiatry as having stumbled from one “single message mythology” to another over the course of its history. The way forward for developing better explanatory accounts, in my opinion, has to be a robust form of scientific pluralism. There are powerful forces at play urging us to adopt one preferred paradigm to the exclusion of others. We have seen that in the critical space with frameworks such as PTMF. The theory of brain energy is to me yet another single message mythology. While I truly support further scientific research on the links between metabolism and psychopathology, I do not want us to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Imagine if someone came out with a 'there is just one cause of all physical illness' theory today. They'd be laughed off the stage. ... This is an excellent review. I too found the brain energy idea intriguing, exciting really, when I first encountered it. Causal reductionism is very alluring indeed, even to those of us who might be expected to know better. It would be so awesome WERE it to be true, since it gets rids of complexity and is very encouraging re treatments. But, well, yes, we've seen it all before!

Superb essay. Kendler would approve. Wouldn't it be nice if it were all about my mitochondria, and yet and yet and yet, I still seem to feel like I'm damned if I do and damned if I don't. . . .Do you happen to know anyone I can talk to about that?