From Here to Humility

At every stage, a clinician must be willing to acknowledge that they do not have all the answers

Stephanie Foster is a Registered Psychologist in Calgary, Alberta. She is in private practice and has provided short and long-term psychotherapy in a variety of treatment settings.

One day I asked myself, “Is humility the most important quality in a therapist?” I answered in the affirmative, gave myself a premature pat on the back, and set forth to pen an article. As research progressed, it quickly became apparent that I had miscalculated the breadth of the topic. Humility is a concept with a rich history in spiritual, religious, and cultural traditions (Akhtar, 2018; Kravis, 2013). Too proud to admit being in over my head and too impatient in general, I pivoted to the idea that a therapist’s most important quality is restraint. A perceptive colleague pointed out that therapeutic restraint is rooted in humility, as the virtue rests on the recognition that the world does not revolve around one’s own needs. Emboldened by the support and mortified by the size of the project, I started again. To explore a particular virtue might imply that one is a spokesperson for it, so I will declare that my humility is under construction and scheduled for completion in 2099. In discussing humility and clinical practice, Arnold Richards (2003) noted, “…we are imperfect messengers of the causes we espouse…” (p. 79).

A therapist should be humble: this is not breaking news. In the abstract, nearly everyone recognizes humility as an important clinical virtue. It is this very abstraction that renders the topic challenging because everyone seems to have their own definition of humility. In the film When Harry Met Sally, Carrie Fisher’s character remarks, “Everyone thinks they have good taste and sense of humor, but they couldn’t possibly all have it.” By the same token, most clinicians think they are humble (by their own definition) and we may not agree (based on ours). Contrary to popular opinion, humility is not a meek or aw-shucks disposition. Humility means having enough confidence in one’s strengths to acknowledge limits. It is not thinking oneself unimportant but inviting others to feel equally important. The humble person strives to maintain a view of themselves that is neither inflated nor depreciated; it is a self appraisal that mirrors reality. Realistically, clinical work will be an ongoing education in humility (McWilliams, 2004).

The German word besserwisser translates to “better-knower.” Far from a term of endearment, it describes a smart aleck or know-it-all. In contrast to humility, a better-knower is someone we might label as arrogant. In the mental health professions, those who have yet to be humbled often reveal know-it-all leanings. A better-knower might assert that they know the single cause of every problem or present rigid ideas about treatment duration. The clinician who confidently asserts that all treatments should last not more than six sessions is as much of a know-it-all as one who insists that it must last six hundred; arrogance is versatile. A better-knower, overtly or covertly, makes claims of specialness; an air of self-appointed superiority is the better-knower’s calling card. The exaltation of one’s own point of view and importance is antithetical to humility and deeply problematic in the practice of psychotherapy. Without proper attention to mutuality, the power differential all but ensures that the therapist will occupy the position of better-knower. This position can be quite gratifying for a therapist’s ego, so one must be cautious about overindulging in it. While the therapist occupies the expert role, this can be managed respectfully and humbly. A skilled practitioner is appreciated, the arrogant one usually is not.

In the collegial sphere, the majority of eye-rolling events can be traced back to the nearest better-knower. This is the person who travels with a portable lectern so that they can speechify on-the-go. The better-knower operates on the assumption that everyone wants their opinion as much as they wish to give it, often treating colleagues like pupils. The supervisory tone is unwelcome in most situations yet it makes more appearances than Ryan Seacrest. The better-knower position is easy to slip into because it feels good (to us) but tends to be a drag for everyone else. A humble stance requires endless recalibration, as the desire to put “me first” is part of the human condition. Reality will always be humbling and the question is whether or not we can integrate the lessons. The exploration of clinical humility in our field, how it appears and when it goes missing, helps us to reflect on our own behavior and that of our colleagues. We may think we recognize clinical humility, but do we? We may think we are humble, but are we? The willingness to ask ourselves these questions is a humble beginning.

Listening is in itself an act of humility – Salman Akhtar

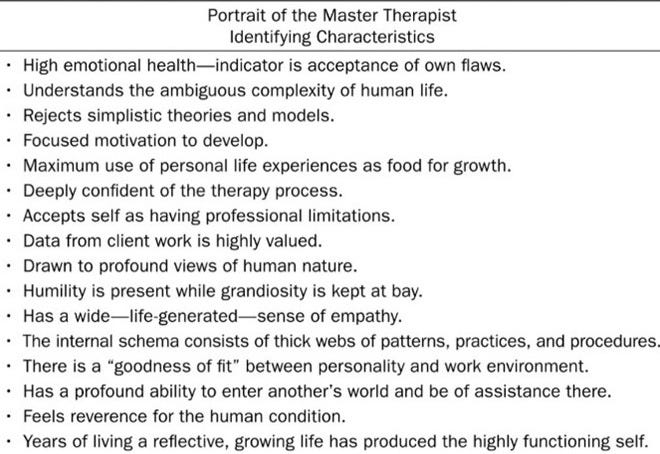

A psychotherapeutic treatment is, above all else, focused on the best interests of the patient. The psychotherapist offers a unique devotion that “… is at root one of professional responsibility in the service of another person’s mental freeing up and growing” (Poland, 2018, p. 46). How might a professional embody this unique form of dedication? The study of skilled clinicians reveals a bundle of laudable qualities, including a commitment to personal growth, a respect for the complexity of human experience, and empathy (Skovholt & Jennings, 2016). I argue that these qualities, while undoubtedly multifaceted, tend to flow to or from humility. Akhtar (2018) offers an overview of humility as a “silent virtue”:

Pooling together the various features attributed to ‘humility’, one finds that the attitude is comprised of (i) a self-view of being ‘nothing special’ without masochistic disavowal of one’s assets, (ii) an emotional state of gratitude and tenderness, (iii) a cognitive attitude of openness to learning and considering one’s state of knowledge as non-exhaustive, (iv) a behavioural style of interacting with others with attention, respect, and politeness, and (v) an experiential capacity for surrender and awe (p. 120).

Akhtar’s overview of humility bears a strong resemblance to the portrait of a master therapist. In the consulting room, it is the ability to balance caution and confidence, a collaborative spirit, and a capacity for self-reflection. Humility is often mentioned as an important quality in a therapist, but given its impact on the other virtues, it may be the important quality in a therapist. The humble clinician is capable of unselving (Marcus, 2012), which is characterized by the lack of self-preoccupation. It is understanding that the world does not revolve around me. Humility has been described as not thinking less of oneself but the freedom from thinking of oneself at all. This is more poetic than pragmatic as no one is ever completely free from thinking about themselves. To conduct psychotherapy effectively, the clinician must be committed to unselving to the extent that it facilitates clinical work. Professional boundaries help to create the conditions required for appropriate unselving and the treatment frame is designed to evoke this from the clinician. The ingeniousness of the treatment frame is that it allows the clinician to put the patient first without putting themselves last. In this way, the frame might be considered a technical expression of humility.

Humility can and does coexist with genuine confidence, vital in the helping role. A clinician’s stock-in-trade is knowing what to say, how and when to say it, and when to say nothing at all. Far from shooting the breeze, skillful therapeutic work requires expertise. This expertise is not a gift from the heavens; clinicians who examine and question their own work tend to be the best performers (Nissen-Lie et al., 2017). Healthy self-scrutiny, which is rooted in humility, allows the professional to seek and find room for improvement (Hook, Watkins, Davis, & Owens, 2015). The humble clinician is willing to face their shortcomings in the service of growth which, paradoxically, requires confidence: “Being able to not-know is not the same as having no knowledge. It is being humble about the limits of our knowledge. Humility is the child of self-assuredness” (Peebles, 2022, p.81). This looks like the professional who seeks feedback from their patients and colleagues, honoring the contribution of others rather than assuming that one’s own knowledge is the be-all and end-all: “The expert psychotherapist is foremost a humble psychotherapist” (Hook et al).

Humility might be the load-bearing wall of effective clinical practice. A clinician must know their value while not overinflating it. This struggle is nowhere more evident than in the consulting room, as the balance between the self and other is the highwire act of clinical practice. A clinician walks this tightrope every session, subordinating many parts of themselves in service of clinical work. Given the therapist’s professional dedication to the lives of others, good therapeutic work has been described as narcissistically depriving (Kravis, 2013). The hoped-for gratifications may be long in the making, if they come at all. The therapist is not the center of attention; psychotherapy is the patient’s show (Poland, 2018). As the professional deprivations accumulate and restorations are underway, humility holds up the clinical house.

In addition to the necessary sacrifices of the role, there is the not-so-small matter of uncertainty. When therapists are being honest about the work, they will tell you that they are often wondering what to say or do next. For most, being in the dark is not a self-esteem enhancer and therapists a good bit of time fumbling around in it. If you enjoy a life of self-doubt, welcome to the practice of psychotherapy:

The neat theories that can feel reassuringly definitive when encountered in classes or textbooks give way to a messy human reality that is much more enigmatic… Any therapist who claims that he or she confidently knows what to do most of the time probably isn’t paying close enough attention to what is actually transpiring in the room (Wachtel, 2011, p. 3).

Psychotherapy is a high-stakes, high-ambiguity enterprise. This ambiguity can be disquieting, especially when we are being paid with the expectation of having answers. It is easy to overvalue our ideas because in times of doubt, we tend to cling to them. The overidentification with theories and ideas tends to be on full display in collegial forums, where clinicians get into their lanes and race each other to the last word. The humility required in the consulting room may result in a fair amount of pent up energy for collegial showboating:

… the work of therapy is so difficult, and its strains on our normal self-esteem and exhibitionism so great, that [therapists] need narcissistic stabilization more than other people do and therefore seek out-of-the-office opportunities to be bigshots (McWilliams & Lependorf, 1990, p. 438).

While the vicissitudes of practice make it difficult to routinely impress our patients, or even ourselves, it can be gratifying to dazzle our colleagues. It is much easier to talk about psychotherapy than it is to do it. While patients see the therapist that we really are, we can elect to show colleagues the therapist that we hope to be.

Vanity, thy name is everyone – Warren Poland

In a career where one is primarily the listener, being the speaker often comes as a welcome relief. Clinicians find teaching, supervising, writing, speaking, and creative expression to be vital outlets for the energies clinical work holds in reserve. A hybrid of professional and social engagement, our collegial forums are something of a professional stage. In this spotlight, the clinician gets to show off a little, receive recognition, and release some exhibitionistic steam. As self-involved as this sounds, it is actually pretty healthy. It is a means of meeting personal needs outside of the consulting room, connecting with colleagues, and distributing knowledge. Professionals want to share all that they know and we need them to—this is how we learn. When all goes well, colleagues are our resources, mentors, and comrades.

The seeds of humble collegiality can be planted or uprooted in the earliest stages of one’s career, beginning with supervision. Here, it is up to supervisors to set the example. A supervisor is in a position of power and often idealized by the supervisee, making supervision something of a litmus test for humility. A better-knower with a me, me, me disposition often takes full advantage of the power differential that supervision sets up. When the supervisor treats the process as a personal showcase rather than a staging ground for someone’s career, the essence of mentorship evaporates. In hushed tones, several colleagues have shared that arrogant supervisors harmed their development and, in some cases, nearly turned them off the profession. They described feeling put down by supervisors who would talk at them instead of with them. As arrogance has many faces, supervisors who treat the supervisee as an afterthought are also revealing their self-involvement. I have heard many diplomatically describe their supervisory experience as “hands off”; I suspect this is code for “My supervisor didn’t give a damn about me.” The imperious and inattentive supervisor sends a similar message to their trainees: I am important, you are not. If these supervisors are remembered, it is usually in the form of a cautionary tale. A humble supervisor allows trainees to feel valued, even when they struggle. Humble supervision is knowing but not all-knowing. A humble commitment to the trainee’s professional growth is a true contribution to the discipline.

For supervisees, receptivity to learning requires one to humbly acknowledge that they are beginners. Naturally, most trainees want the approval of their superiors and while critical feedback always stings, most are eager to improve their skills. Although the vast majority are receptive learners, teachers and supervisors will regularly encounter better-knowers in a pool of trainees. As a colleague recently shared with me, “There is at least one in every classroom.” These individuals are typically convinced that they are smarter than their professors, supervisors, and cohort. They tend to present more like the resident expert than the humble beginner. Nancy McWilliams describes the frustration of working with these types of supervisees, whose attitude she describes as, “‘I can show you how it’s done’ rather than ‘I could use your help’” (2021, p.175). The better-knower stance in training is more of a red flag than a green light, as one who is unwilling to learn from a supervisor is displaying a troubling tendency towards unearned confidence: “I’ve trained scores of therapists only to find that the self-doubting ones worry me a lot less than those that are overly certain” (Balick, 2025). The importance of humility in clinical work shows up early. Humility is vital for professional growth, but it also serves to protect patients from the dangers of clinical hubris. At every stage, a clinician must be willing to acknowledge that they do not have all the answers.

The willingness to accept feedback from our colleagues is not only a mark of humility but a cornerstone of collegiality: “Treating each other as if we can learn from the other cultivates an ambience of respect and hospitality in our professional homes” (Orange, 2015, p. 258). Alas, respect and hospitality are routinely edged out by infighting, backbiting, and condescension. Professional societies have a long history of discord, the tales of which are beyond the scope of this article. Suffice to say, collegial strife has always been there and does not appear to be leaving anytime soon. In the modern era, professional battles often play out in online forums, leading to interactions more evocative of Jerry Springer than of scholarly discourse. Be it online or offline, we all want to be admired by our colleagues and some achieve this by drowning everyone else out. There is a difference between sharing knowledge and being a know-it-all; the first is a bid for connection, the second is a barrier to it. Humility matters in the collegial sphere for the same reason as in the clinical one: it permits genuine connection. These connections are vital because psychotherapy can be a daunting profession. The work can deplete, test, and unsteady the most stalwart clinician. Collegial connections serve to rejuvenate and protect us:

A profound “yes” to our limitations constitutes the most important advantage of humility, both personal and professional. Knowing this and working with colleagues and supervisors at every stage of our work, protects us from ethical transgressions and from various failures. Humility keeps our courage from being brash, hubristic, and overconfident (Orange, 2015, p. 246).

Quite simply, therapists need other therapists. I have no idea how anyone makes it in this profession in isolation. Clinical work is never short on complexity and I am thrilled to have colleagues willing to offer their perspective. When colleagues seek me out, I am humbled that they have sought my counsel. Despite the fact that we talk with people all day, the practice of psychotherapy is marked by a certain solitude. Good colleagues keep us company outside of the consulting room and we hold them in mind inside of it, so as to never feel alone in our office. In my view, humility and collegial rapport go hand in hand. The capacity to love requires humility and gratitude (Kernberg, 2011), and the capacity to work well with our colleagues asks very much the same. Arrogance tends to fracture community while humility adheres it.

Morris Eagle (2012) tells the story of a colleague that he would choose as his own therapist based on his sense of someone as a “real person,” despite disagreeing with the bulk of his theoretical comments. He contrasted this with a colleague whose perceived insincerity made him feel as though he wanted to throw up. I can think of dozens of similar examples that I have personally experienced, some involving nausea. These anecdotes underscore the well-established fact that the person of the therapist is critical to the treatment (Norcross, 2011; Skovholt & Jennings, 2016). If we are humble enough to acknowledge that our strengths and weaknesses show up in clinical work, we are realistic enough to know that the same is true of our colleagues. We can talk about theory, techniques, and resumes all day long but, in the end, our profession is a personal one: “… we don’t refer to people based on their theoretical allegiances. We refer to people based on our sense of their character” (Grossman, 2023). Humility is a professional plus and it cannot be faked just to get more referrals (although I have seen a few give it a try). We are all more human than otherwise and, in the consulting room, we are probably more ourselves than otherwise. Our colleagues know this very well.

Our colleagues often know us pretty well, too. To riff on the phrase, “it takes two people to understand and help one,” it similarly takes two colleagues to improve one. If you have not had a supervisor offer critical feedback, you have not had the benefit of a good supervisor. If a colleague has never asked you to look in the mirror, you are probably surrounded by sycophants. If you only have an ear for praise, you are tone-deaf to reality. A good colleague will humble you now and then. This is how professional growth happens. Painful? Yes. Necessary? Yes. When we are not learning about our mistakes through our patients, we are learning about them through our colleagues. This comes in many forms, from direct feedback to simply realizing that a colleague is much better at the work than we might be. A humble person treats an encounter with a more skilled person as a gift, the better-knower treats it as a threat. When envy predominates, it leads to stagnation that is both professional and personal.

Our true professional allies are friend enough to be steadfast and colleague enough to be forthright. If we have the humility to bear about the truth our shortcomings, we may also have the privilege of being genuinely applauded for our strengths. For a humble person, reality is not an aggression but an anchor. Humility allows us to take in appreciation without surrendering to the temptations of idealization. In the event of disagreement, humility allows us respectfully to hold a position while acknowledging our limits; the humble person is open to persuasion without being a pushover. We can be exceptionally good without thinking that we are better than everyone else. Humility is a high psychic bar and, ultimately, it is those around us who will decide if we have cleared it. In this professional life, we will encounter champions and critics. We strive to listen to both, for it is a long road from here to humility.

See also by Stephanie Foster:

References

Akhtar, S. (2018). Silent Virtues: Patience, Curiosity, Privacy, Intimacy, Humility, and Dignity. Routledge.

Aron, L., & Starr, K. (2013). A psychotherapy for the people: Toward a progressive psychoanalysis. Routledge.

Balick, A. (2025, October 25). Why the world needs more imposter syndrome, not less. https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/why-you-have-imposter-syndrome-and-what-its-for

Ehrlich L. T. (2013). Analysis begins in the analyst’s mind: conceptual and technical considerations on recommending analysis. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 61(6), 1077–1107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065113511988

Falender, C. A., & Shafranske, E. P. (2014). Clinical Supervision: The State of the Art. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(11), 1030–1041. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22124

Friedman, L. (1988). The anatomy of psychotherapy. Analytic Press, Inc.

Gabbard, G. O. (2007). “Bound in a nutshell”: Thoughts on complexity, reductionism, and “infinite space.” International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 88(3), 559–574. https://doi.org/10.1516/E8U0-G516-98G4-11P7

Gabbard, G. O. (2010). Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy : a basic text (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Pub.

The Psychoanalytic Consultant with Glen Gabbard. Host: Harvey Schwartz. IPA Off the Couch Podcast. May 22, 2022.

Hook, J. N., Watkins Jr., C. E., Davis, D. E., & Owen, J. (2015). Humility: The paradoxical foundation for psychotherapy expertise. Psychotherapy Bulletin, 50(2), 11-13. https://societyforpsychotherapy.org/humility-the-paradoxical-foundation-for-psychotherapy-expertise/

Junkers, G. (Ed.). (2023). Living and containing psychoanalysis in institutions : psychoanalysts working together. Routledge.

Karson, M. (2018, October). On being the instrument of change. [Web article]. Retrieved from https://societyforpsychotherapy.org/on-being-the-instrument-of-change

Kernberg, O. F. (2011). Limitations to the capacity to love. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 92(6), 1501–1515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-8315.2011.00456.x

Kravis, N. (2013). The Analyst’s Hatred of Analysis. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 82(1), 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2167-4086.2013.00010.x

Technique is Character Rationalized with Lee Grossman, MD – Episode 135 (Lee Grossman). Host: Harvey Schwartz. IPA Off the Couch Podcast. May 23, 2023. https://ipaoffthecouch.org/2023/05/28/episode-135-technique-is-character-rationalized-with-lee-grossman-md-oakland-ca/

Marcus, P. (2013). On the quiet virtue of humility. In In Search of the Spiritual (1st ed., pp. 89–110). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429475801-5

McWilliams, N., & Lependorf, S. (1990). Narcissistic Pathology of Everyday Life:—The Denial of Remorse and Gratitude. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 26(3), 430–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107530.1990.10746671

McWilliams, N. (2004). Psychoanalytic psychotherapy : a practitioner’s guide. Guilford Press.

Nissen‐Lie, H. A., Rønnestad, M. H., Høglend, P. A., Havik, O. E., Solbakken, O. A., Stiles, T. C., & Monsen, J. T. (2017). Love Yourself as a Person, Doubt Yourself as a Therapist? Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 24(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1977

Norcross, J. C. (2011). Psychotherapy relationships that work : evidence-based responsiveness (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Orange, D. M. (2015). Nourishing the Inner Life of Clinicians and Humanitarians: The Ethical Turn in Psychoanalysis (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315676814

Paine, D. R., Sandage, S. J., Rupert, D., Devor, N. G., & Bronstein, M. (2015). Humility as a Psychotherapeutic Virtue: Spiritual, Philosophical, and Psychological Foundations. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 17(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/19349637.2015.957611

Peebles, M. J. (2022). When psychotherapy feels stuck. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315449043

Poland, W. S. (2018). Intimacy and separateness in psychoanalysis. Routledge.

Richards, A. (2003). Psychoanalytic Discourse at the Turn of Our Century: A Plea for a Measure of Humility. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 51, 73–89.

Safran, J., Shaker, A., Boutwell, C., & Cavalca, E. (2012). Interview with Morris Eagle. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 29(2), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027897

Skovholt, Thomas M., and Len Jennings (eds), Master Therapists: Exploring Expertise in Therapy and Counseling, 10th Anniversary Edition (New York, 2016) https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780190496586.001.0001

Tangney, J. P. (2000). Humility: Theoretical Perspectives, Empirical Findings and Directions for Future Research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.70

Wachtel, P. L. (2011). Inside the session : what really happens in psychotherapy (1st ed.). American Psychological Association.

Thank you for this article. Your respect for practice is captured and expressed poignantly. I resonate so much with your description of the solitude of practice and importance of colleagues. I agree that there’s no question the therapist’s personality is in the room, which follows given how integral one’s humility is to the work.

Your portrait checklist is spot on. In essence, treatment excels in the context of trust in the clinical relationship- and is fertilized by the therapist's ability to be fully present (putting ego aside), natural (self possessed, embracing personal stories vs blinded) and comfortable with personal charter traits (all of them).... certainly humility is a cornerstone this process