Is ketamine as good as placebo or as good as ECT?

Two recent RCTs investigating the use of ketamine in the treatment of depression raise interesting questions for us to reflect on.

The first RCT is currently available as a preprint, Trial of Ketamine Masked by Surgical Anesthesia in Depressed Patients, by Theresa Lii, et al on medRxiv (it has not yet undergone peer-review, so usual limitations apply). It generated an excited debate on twitter when the senior author, Boris D. Heifets, posted the results in a twitter thread.

Ketamine, a dissociative anesthetic, has demonstrated rapid antidepressant effects in multiple clinical trials. A 2019 paper in Neuron by Krystal et al., summarized clinical efficacy as follows:

“These replications found that a single dose of ketamine produced antidepressant effects that began within hours, peaked within 24 to 72 h, and then dissipated typically within 2 weeks if ketamine was not repeated. Also, the subsequent studies showed that ketamine was effective in antidepressant non-responders, including patients with bipolar disorder. Further, the antidepressant effects of ketamine were meaningful clinically, with one-third of patients with treatment-resistant symptoms achieving remission and ∼50%–75% of patients demonstrating clinical response from a single dose, with higher rates of response and remission with repeated administrations.”

McIntyre et al. agreed with this assessment of efficacy in a 2021 paper for the American Journal of Psychiatry: “Replicated short-term randomized controlled studies have unequivocally established the rapid and significant efficacy of both formulations (ketamine and esketamine) and routes of delivery in adults with TRD [Treatment Resistant Depression].” They, however, note in the paper:

“A legitimate criticism, as it relates to interpreting the effect sizes reported with single or repeat-dose ketamine in TRD, is the possibility that nonspecific effects such as functional unblinding (e.g., by patients experiencing dissociation or euphoric responses) and expectancy may inadvertently inflate the efficacy of ketamine.”

Prior studies have used midazolam (a short-acting benzodiazepine used in anesthesia) as an active control, which, while better than normal saline, is generally considered inadequate as the psychoactive effects of ketamine are fairly distinct from midazolam. Inflated efficacy is not the only worry; some critics have maintained that the antidepressant effects of ketamine may be entirely explainable by unblinding and expectancy. In this context, Lii et al. study is important because it uses a creative trial design to ensure successful blinding of ketamine.

Here are the methods and results as described in the abstract:

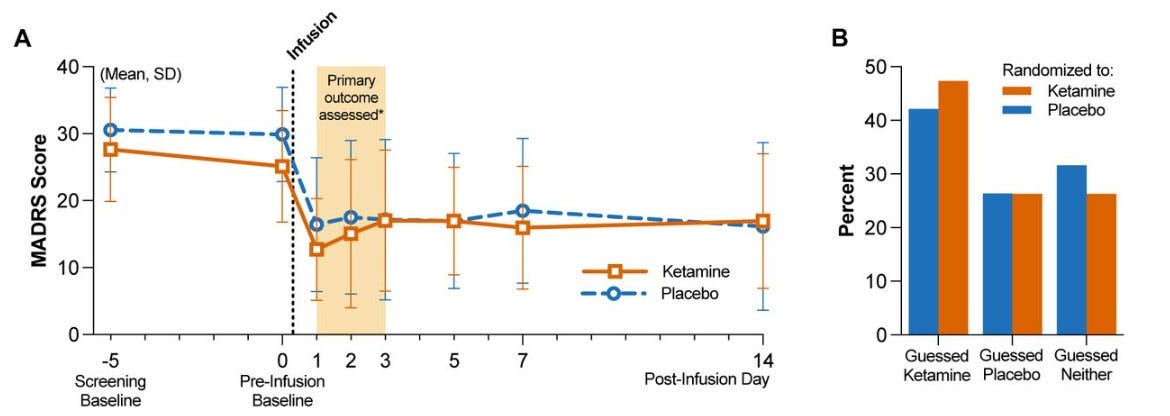

METHODS In a triple-masked, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, 40 adult patients with major depressive disorder were randomized to a single infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or placebo (saline) during anesthesia for routine surgery. The primary outcome was depression severity measured by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) at 1, 2, and 3 days post-infusion. The secondary outcome was the proportion of participants with clinical response (≥50% reduction in MADRS scores) at 1, 2, and 3 days post-infusion. After all follow-up visits, participants were asked to guess which intervention they received.

RESULTS Mean MADRS scores did not differ between groups at screening or pre-infusion baseline. The mixed-effects model showed no evidence of effect of group assignment on post-infusion MADRS scores at 1 to 3 days post-infusion (-5.82, 95% CI -13.3 to 1.64, p=0.13). Clinical response rates were similar between groups (60% versus 50% on day 1) and comparable to previous studies of ketamine in depressed populations. Secondary and exploratory outcomes found no evidence of benefit for ketamine. 36.8% of participants guessed their treatment assignment correctly; both groups allocated their guesses in similar proportions.

Here are some additional considerations:

The trial had a small sample size, but it was rigorously designed and conducted.

Observed improvement in depression at day 1 with ketamine and placebo was similar to the improvement reported in previous ketamine trials in awake patients. That is, improvement seen in ketamine group in this RCT was within the expected range, but the improvement seen in the placebo was much higher than expected.

Propofol infusions and inhaled isoflurane have shown antidepressant properties in trials when given at doses that suppress EEG activity over multiple administrations, but this was not the case for the standard general anesthesia used in this study. N2O has also demonstrated antidepressant effects in clinical trials, however, only 3/40 participants in the current study were exposed to N2O at relevant concentrations.

Ketamine group had a longer median depressive episode duration (38 months) compared to the placebo group (17 months).

“a major limitation of our study is that we did not measure treatment expectancies prior to randomization. Therefore, we cannot definitively conclude that subject-expectancy bias mediates the causal relationship between effective masking and smaller treatment effect sizes.”

What does this all mean? What are we to make of this?

One possibility is that the skeptics have been correct all along, and ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effects are nothing but expectancy effects and “placebo.” This possibility remains in play, but it is not the only possibility.

Since the magnitude of ketamine effects in this RCT are comparable to existing trials, the more surprising result is the high response in the placebo group, far higher than what has been seen in prior ketamine trials. High expectancy appears to be the likely driver. (A less likely explanation is that general anesthesia itself has an antidepressant effect. People generally don’t respond to surgery under general anesthesia with a rapid improvement in mood.) Perhaps in previous ketamine trials with inadequate blinding, subjects in placebo group started off with high expectancy but then quickly realized that they had received placebo, which led to lower improvement in depression in the placebo group. But in this trial effects of high expectancy were maintained due to effective blinding. It is crucial to note that expectancy was not directly measured in this RCT, so hypothesis about its role is somewhat speculative. (People were asked to guess their treatment assignment after all follow-up data had been collected, but their predictions at that point were likely influenced by whether they felt their mood had improved. That is, if they felt better, they would predict they received ketamine.)

It is also possible, we can speculate, that general anesthesia reduces the benefits of ketamine. Perhaps optimal improvement with ketamine requires being conscious. Perhaps the conscious experience of psychoactive effects with ketamine is important, and taking it away reduces the response (existing analyses examining whether dissociative effects are linked to antidepressant effects have produced mixed results; the general opinion is that they are not linked). While the response to ketamine was comparable to existing trials, the elevated placebo response allows for the possibility that response with ketamine could’ve been even higher had the subjects been awake during administration.

Another possibility is that under certain circumstances, expectancy effects can be as large as active treatment effects with ketamine. That is, it’s not the case that ketamine antidepressant effects are nothing more than expectancy effects, but rather that in certain situations expectancy effects can be as large as active treatment, such that no superiority is demonstrated. The only way to distinguish between these possibilities is by better understanding, measurement, and differentiation of the mechanisms by which expectancy and ketamine (and other psychiatric interventions) produce their effects. Qualitative and phenomenological investigations may also reveal important differences. RCT designs that are agnostic about mechanisms and only care about separation from placebo are ill-equipped to distinguish between ‘as effective as placebo’ and ‘nothing more than placebo.’ Nonetheless, since the default assumption in RCTs is usually the skeptical assumption, this trial raises serious questions about the efficacy of ketamine in the treatment of depression.

The second RCT is a ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine. It is relatively straightforward compared to the trial we just discussed, and the basic facts are as follows:

It was an open-label, randomized, noninferiority trial involving patients referred to ECT clinics for treatment-resistant major depression without psychosis.

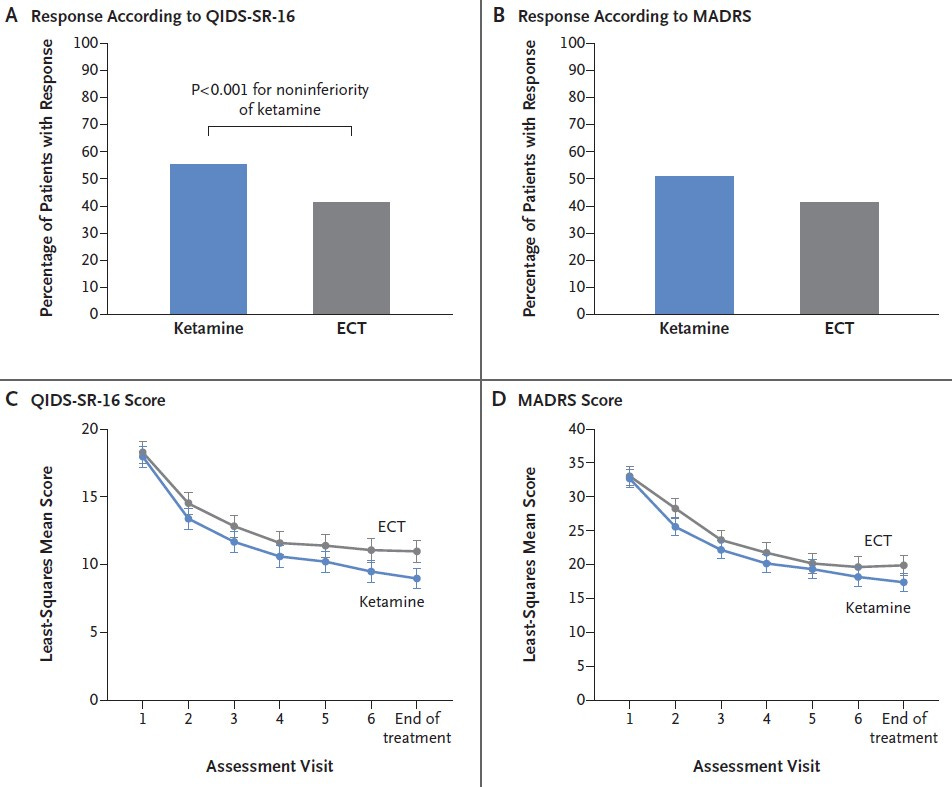

During an initial 3-week treatment phase, patients received either ECT three times per week or ketamine (0.5 mg per kilogram of body weight over 40 minutes) twice per week.

The primary outcome was response to treatment (i.e., a decrease of ≥50% from baseline in self-reported depressive symptoms)

After the initial treatment phase, patients who had a response were followed over a 6-month period, receiving further treatment guided by their clinicians.

Ketamine was administered to 195 patients and ECT to 170 patients.

At the end of 3 weeks, 41% of the patients in the ECT group and 55% of those in the ketamine group had demonstrated a response to treatment.

By the end of the 6-month follow-up period, relapse had occurred in 56% of the patients in the ECT group and in 34% of those in the ketamine group.

Ketamine was noninferior to ECT for treatment-resistant major depression without psychosis.

Robert Freedman in an accompanying commentary noted that “these patients represent a severely affected, chronically ill group of men and women with depression in midlife. All had had multiple episodes of depression with onset in adolescence or early adulthood. Most had family histories of depression, and many had made suicide attempts. Most patients had coexisting severe anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder, and some had coexisting alcohol use disorder. All the patients had been treated with a wide range of psychotropic medicines. Some had received previous treatment with either ECT or ketamine.”

Several aspects of the trial placed ECT at a relative disadvantage:

It appears that patient preference was skewed towards ketamine. The authors note, “The percentage of patients who withdrew from the trial after randomization but before treatment was started was higher in the ECT group than in the ketamine group, a finding that reflects patient preferences and logistic issues.”

ECT has been shown to be more effective for older adults, major depressive disorder with psychosis or catatonia, and in inpatients. This trial excluded subjects with psychosis and catatonia, and it was conducted in primarily outpatients with mid-life depression. Also, “ECT was started with right unilateral placement and was then switched to bilateral placement in the event of inadequate response. If ECT was started with bilateral placement, a higher percentage of patients with a response might have been observed.”

A large sample size, involvement of multiple centers, and reliance on patients referred to ECT clinics makes the ketamine vs ECT RCT a lot more ecologically valid than the ketamine-under-surgical-anesthesia RCT. However, from a trial methodology perspective, it is much less rigorous. It is open-label, while the other trial is perfectly blinded. When it comes to ketamine, this appears to be a serious dilemma: blinding may be achievable only at the cost of ecological validity.

A large sample size, involvement of multiple centers, and reliance on patients referred to ECT clinics makes the ketamine vs ECT RCT a lot more ecologically valid than the ketamine-under-surgical-anesthesia RCT. However, from a trial methodology perspective, it is much less rigorous. It is open-label, while the other trial is perfectly blinded. When it comes to ketamine, this appears to be a serious dilemma: blinding may be achievable only at the cost of ecological validity.

If the skeptical takeaway from the anesthesia-blinding trial is that the antidepressant effects of ketamine are all driven by expectancy or placebo, then the ketamine vs ECT trial presents some interpretative challenges. Can ketamine’s non-inferiority to ECT be explained entirely by expectancy? If so, what prevents us from extending our skepticism to ECT itself, widely regarded as the most effective treatment for depression? ECT does outperform sham ECT in RCTs (although trials are old and low-quality) and we do see differences in RCTs between unilateral vs bilateral ECT and low-dose vs high-dose ECT, so the case for skepticism about ECT’s efficacy is weak. But accepting ECT as effective while dismissing ketamine as placebo nonetheless leads to the troubling conclusion that placebo can be as good as ECT.

If we can take a group of patients with chronic, serious, and treatment-resistant depression, and we can get results that equal, or even exceed, those of ECT, results that maintain some degree of benefit over 6 months of follow-up, simply by virtue of expectancy and unblinding, then this is a state of affairs that does not make much clinical sense! If that is indeed the case, and if expectancy is such a powerful cure, why even bother with ECT? Why not offer increasingly intricate sham medical rituals with none of the serious side effects?

If we can take a group of patients with chronic, serious, and treatment-resistant depression, and we can get results that equal, or even exceed, those of ECT, results that maintain some degree of benefit over 6 months of follow-up, simply by virtue of expectancy and unblinding, then this is a state of affairs that does not make much clinical sense! If that is indeed the case, and if expectancy is such a powerful cure, why even bother with ECT? Why not offer increasingly intricate sham medical rituals with none of the serious side effects?

If ketamine works just as well as ECT in the outpatient treatment of treatment-resistant, non-psychotic, major depression, then either ketamine truly is an effective psychotropic or we have been fooling ourselves for decades with ever more complex psychotropic effects, embedded in ever more elaborate rituals, fueled entirely by expectancy, regression to the mean, behavioral reactivity in response to observation, natural recovery, and whatever else goes in “placebo.” This latter conclusion is one that I find very difficult to accept. Based on what I know — from clinical trials, clinical experience, patient experience, basic neuroscience — I do not think it is plausible. But for a skeptic for whom the randomized and perfectly blinded placebo-comparison is the only arbiter of truth, it appears as if this is not only plausible but perhaps the only conclusion worth accepting.

[Comments are open to all subscribers for this post.]

Were they on oxygen under anesthesia? Oxygen at somewhat higher than RA % has shown antidepressant effects. So has nitrous oxide.

If I recall correctly there's some (early) evidence for antidepressant effects from anaesthetics like propofol or sevflurane? Which could explain the unusually high "placebo" response - "Agents used for anesthetic maintenance included intravenous propofol and inhaled sevoflurane or isoflurane" in the "Trial of Ketamine Masked by Surgical Anesthesia in Depressed Patients" paper.

Possibly it's just that the other anaesthetics were also effective antidepressants!