Mental Causation and Metaphysical Gloss

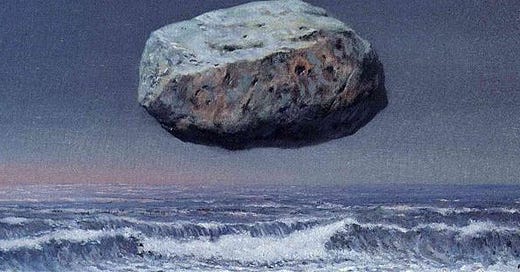

“to call upon the complex interactive nature all at once”

This is a follow-up to:

With my last post on mental causation, in which I took mental causation to be a form of “downward causation” and discussed it in organizational terms, I entered some turbulent philosophical waters. The philosophical literature on topics such as emergence, downward causation, and levels is quite extensive. Some philosopher friends pointed out that it came across as if I was taking a strong philosophical position on the existence of downward causation, but that was not my intention. So this post is an attempt at some clarification.

“Downward causation” is strictly speaking neither “downward” nor “causation.”

It is not downward, because there is no literal downward action; downward is a metaphor about part-whole relationships and the impact of actions of entities described at one scale of organization (e.g., economic policy) on entities described at a different scale (e.g., bodily organs). It is not “causation,” because there is no direct action, no direct force, no inducement to change, no efficient cause, in the modern sense of the word “cause.”

“Downward causation” is causation in the same sense as the centrifugal force and the force of gravity are forces. They aren’t forces in the technical sense, but they appear to be forces, and can be treated as forces as long as we are aware of their true physical nature. We don’t have to call them “forces,” but they refer to actual phenomena that cannot be wished away. We cannot be in a centrifuge and be content with saying “centrifugal force can’t hurt us because it’s not a real force.” In a similar sense, whether we use the words “downward causation” or not, the phenomena it refers to are real and cannot be wished away.

I am grateful to Kristian Kemtrup for introducing me to John Heil’s 2023 excellent article “The Last Word on Emergence” in Res Philosophica. Heil challenges the “metaphysical gloss” that is applied to discussions of hierarchical ontologies, emergence, and downward causation. From what I can tell, I am broadly in agreement with Heil, although I emphasize things a bit differently.

Heil writes:

“Discussions of emergence are tailored to pluralistic ontologies and hierarchical cosmologies. There is, first and foremost, a fundamental level. This yields a hierarchy of successively less-than-fundamental levels, the nature of which requires considerable fancy metaphysical footwork to articulate. But why imagine that the cosmos is a hierarchical affair? You can have levels of organization, mechanistic levels, levels of composition, levels of description, levels of explanation, but ontological levels are another matter.” (my emphasis)

I completely agree with that. I don’t think that the idea of ontological levels makes sense. There is no reason to think that there are levels built into nature in some fundamental sense. I am merely committed to view that we can legitimately talk about levels of description, levels of organization, and levels of explanation. “The world isn’t organized into levels that interact vertically… rather the ‘levels’ are different ways of describing the structure and behavior of a complex system.” (Philip Gerrans, personal communication – April 9, 2024).

Heil:

“What of robust top-down, whole-to-part explanations of the kind we find in the special sciences that Campbell’s examples are meant to illustrate? If the wholes in question are, as I am suggesting, highly interactive assemblages of parts, then, in invoking the wholes, this is what is being invoked. You have downward causal explanation, but not downward causation. To say that the particles making up a wheel moved as they did because the wheel rolled, is to call upon the wheel’s complex interactive nature all at once, not to invoke an exciting new—downward, whole-to-part—species of causation.”

“to call upon the wheel’s complex interactive nature all at once”… The way I see it, Heil is saying almost exactly what Deacon is saying, except that Deacon refers to the influence of the entire interactive complex as a variety of Aristotelian “formal cause.” There is no actual downward, whole-to-part efficient cause being posited or proposed.

Heil:

“Wheels and eddies have the macro-characteristics they have owing to the highly interactive natures of the parts that make them up. To say that wheels and eddies are nothing over and above their parts is not to say that wheels and eddies are Legolike collections of molecules. That would be to sell the collections short. Molecules making up the collections are massively interactive, and, in the course of interacting, can inflict changes on one another. Molecules in a collection behave differently behave in new ways—ways they would not behave outside of collections. This is not because they are subject to downward, whole-to-part causal forces, however, it is because they are individually empowered as they are.”

“Molecules in a collection behave differently behave in new ways—ways they would not behave outside of collections.” This is precisely what I was trying to convey as well. The fact that being in a collection changes how molecules behave is what I referred to as “the causal reality of configurations and constraints” and what Deacon refers to as “an alteration in causal probabilities” (by virtue of being a part of a particular configuration of physical processes).

The point is to emphasize that the organization of physical processes matters. New configurations of matter produce new behavior that is not demonstrated outside of these configurations, and to refer to these configurations as causes/explanations is to call upon their complex, interactive nature all at once.

The reason this is important is because in breaking things down into components to look for scientific explanations, we can end up missing the fact that it was the configuration that held the explanation we were looking for.

Terrence Deacon writes in Incomplete Nature:

“All the material and energetic features of a given system are subject to mereological analysis without residue. There is nothing left out… If the constraints rather than the properties of parts are what determine the causal power of a given phenomenon, then a reductive analysis that decomposes a complexly constrained phenomenon into its observable parts and relationships can end up dropping out what may be the critical feature… all trace of these constraints will be “erased” by simple decomposition, unless the history of this higher-order constraint generation is already assumed.” (p 204)