Mental Disorders Both Are and Are Not Brain Diseases

In a new JAMA Psychiatry paper, Kenneth Kendler discusses the question, “Are Psychiatric Disorders Brain Diseases?” Similar to Anneli Jefferson in her recent book, Kendler begins by recognizing that the two traditions positions on this issue are problematic.

The first position is a metaphysical one about the emergence of mind and its instantiation within the brain: since psychiatric disorders are instantiated in the brain, they must be brain disorders. Kendler rightly recognizes that this argument is “not helpful”:

“All mental experiences—normal and psychopathological—are equally brained. Declaring disorder X to be a brain disease is uninformative.”

The second position depends on a concept of brain disease that looks for detectable pathology in brain tissue, such as tumors, strokes, traumatic injuries, and neurodegeneration. Kendler finds this concept to be “outmoded,” one that has failed to keep up with the complexity of neuroscientific mechanisms.

Kendler suggests that we focus on a more modest question: “Can we show that critical causal pathways to psychiatric illness occur in the brain?” and he focuses on psychiatric genetics to answer it. In the context of genetics, the question then becomes: is the link between risk genes and psychiatric disorders mediated by the brain?

He uses the example of schizophrenia to elaborate:

“Our paradigmatic example is the 2022 report of a Genome Wide Association Study of schizophrenia from the Psychiatric Genomic Consortium Schizophrenia Workgroup. In that article, they examine the association between many discovered schizophrenia risk variants and the expression of the relevant genes in 37 human tissues. Significant elevations are seen in 11 tissues, all reflecting different brain regions and specifically neurons. That is, no statistical elevation in expression of schizophrenia-risk genes was seen in any other part of the human body except the brain. These results provide strong support for the hypothesis that a substantial proportion of the genetic risk for schizophrenia results from the expression of these genes in brain, that is: schizophrenia risk genes → brain → schizophrenia. Does this mean that we can now declare that schizophrenia is a brain disease? Not in the old 19th century sense. But we can make the more modest claim that the effect of the strongest known risk factor for schizophrenia—genetics—largely occurs in brain tissue. Other results pointing in this direction are emerging from related methods applied to major depression and bipolar disorder.”

He notes that it cannot simply be taken for granted that the gene expression would be in brain tissue.

“For example, a meaningful proportion of the genetic risk variants for alcohol use disorder are not expressed in brain, but rather in liver and gastrointestinal tissues and evidence is emerging that genetic risk for eating disorders may be partly mediated by metabolic processes.”

In doing so, Kendler transforms “are mental disorders brain disorders?” from a question that is fundamentally about making sense of psychopathology across the mind-body divide to a question of “in which bodily tissue are risk genes for psychiatric disorders expressed?”

Genes, if they are expressed, have to be expressed somewhere in bodily tissues. Genes cannot be directly expressed in the mind because the mind isn’t a substance. Genes influence behavior only by influencing physiology. There’s simply no other way for genes to do that. To what extent are genes expressed in the brain is an open question, and certainly an important one, but it doesn’t address the reasons that drive people to ask, “Are mental disorders brain disorders?” People are not worried about whether genes are expressed in the brain or in the liver; they are worried about something else entirely.

Neo-Kraepelinian assumptions about the existence of undiscovered psychiatric disease entities were dominant in psychiatry in the decades following DSM-III, and implicitly guided the manner in which psychiatric research, psychiatric training, and public education campaigns were conducted. The assertion that mental disorders are brain disorders was an expression of the neo-Kraepelinian worldview, one that is dying for sure but not quite dead yet. Any contemporary proponent of “mental disorders are brain disorders” has to confront the likely possibility that brain mechanisms and processes of psychopathology are heterogenous through and through, and do not coverage onto categorical disease entities (except in isolated cases, such as psychosis caused by autoimmune encephalitis).

Here’s how the dynamic has often worked:

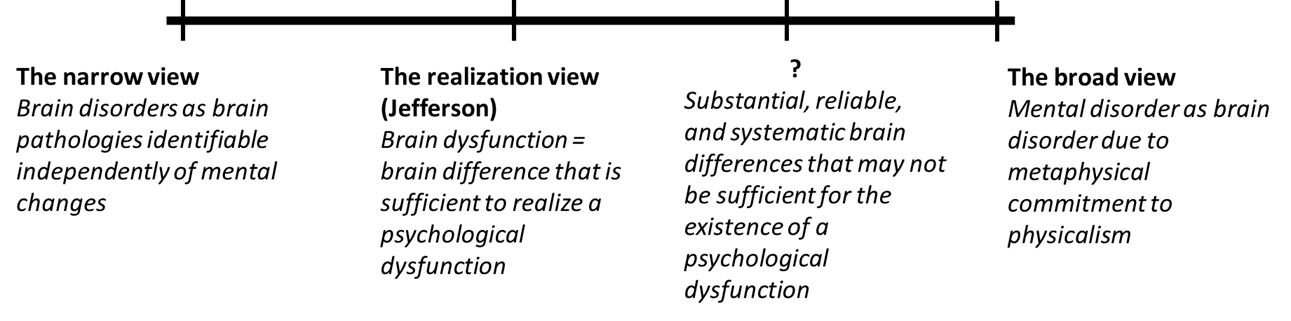

People would assert that mental disorders are brain disorders in the metaphysical sense – mental states are realized by the brain in some form or fashion, therefore, mental disorders are also realized by the brain, and therefore they are brain disorders. However, this broad view would then be conflated with the narrow view in which mental disorders are understood to be expressions of pathological changes in the brain, similar to Parkinson’s disease. This conflation has led to etiological research programs devoted to finding the pathological changes in the brain that were simply assumed to exist. It was assumed that physiological, psychological, and social risk factors would converge on this pathological process in the brain, and understanding and addressing this pathological process would be the key to addressing mental disorders.

Psychiatrists, psychologists, and social scientists have resisted the assertion that mental disorders are brain disorders because of the ease with which the narrow view is conflated with the broad view (in a motte-and-bailey style fallacy), and because of the manner in which it suggests (inadvertently or advertently) that brain processes are more fundamental to a scientific understanding of psychopathology than, say, cognitive and psychodynamic processes. (There are anti-psychiatrists and critical psychiatrists as well who resist the assertion that mental disorders are brain disorders, but their resistance is based on an unscientific worldview, a devotion to unfounded dichotomies, and a denial of the existence of brain mechanisms of behavior.)

It is imperative for us to ask what the relevant contrast for “brain disorder” is. “Condition X is a brain disorder”… versus what other kind of disorder?

From the perspective of gene expression, the contrast becomes that of a disorder of the brain vs a disorder of some other physiological system. This is an interesting question to ask and expands the scope of the bodily processes we assume to be involved in psychopathology, but as I mentioned earlier, this isn’t usually the contrast that motivates the question of whether psychopathology is neuropathology. For psychiatrists and psychologists, the contrast is usually a disorder of the mind vs a disorder of the brain.

Psychiatric disorders are disorders of the brain in the general metaphysical sense – but as Kendler recognizes, saying so is uninformative and vacuous. As Jefferson points out, it is simply an expression of one’s commitment to naturalism. Paradigmatic psychiatric disorders are not disorders of the brain in the narrow sense – they are not expressions of a brain process that is identifiable as dysfunctional in an individual without reference to the psychological symptoms and where the dysfunction causally precedes mental symptoms.

In between these two positions is a broad and ambiguous zone where the brain processes associated with psychiatric disorders can be empirically identified with varying degrees of coherence, tractability, explanatory power, and clinical utility. On this spectrum, we can set different empirical thresholds for when we are justified in calling a mental disorder a brain disorder. E.g., I have previously proposed that we can be justified in calling a psychological dysfunction a brain dysfunction if there are substantial, reliable, and systematic brain differences associated with the psychological dysfunction (provided we contextualize these associations within a scientifically robust theoretical understanding of the relationship between brain and behavior, that psychiatric categories involve many areas of the brain, there is no one-to-one mapping, and emotions emerge from a process that involves complex dynamic interactions in a highly context-dependent manner). Kendler uses a different approach to provide an empirical justification: for a condition such as schizophrenia, where genetic vulnerability is a major risk factor, the genes are primarily expressed in the brain. It is a valid strategy, although it applies poorly to psychiatric disorders where genetics isn’t that relevant. (Major depression has a SNP-based heritability of 9% and current polygenic risk score explains approximately 3% of the variance... that is not enough, in my view, to call major depression a brain disease based on gene expression.)

However, perhaps the truth is that in this grey zone, it doesn’t really matter whether we call psychiatric disorders brain disorders or not. What matters is the recognition that:

Mental disorders are disorders because the psychological features are characterized as dysfunctional using behavioral norms (irrationality, disproportionality, severity, etc.)

Mental disorders are mental disorders because they are defined with reference to psychological and behavioral characteristics.

Mental disorders are embodied; they are instantiated by (or mediated by, or emerge from) brain and bodily processes. However, these bodily processes cannot necessarily be characterized as dysfunctional, except in the indirect sense that they mediate psychological dysfunction.

Experiential and psychological processes play a key role in mental disorders; that is, crucial mechanisms and processes of psychopathology require a description in psychological terms.

Mental disorders are multi-level disorders; causal risk factors and processes exist at multiple levels of explanation, and these risk factors and processes interact in complex webs of causation.

Mechanisms and processes involved in psychiatric illness do occur in the brain; the embodiment of mind necessitates that this will be so. However, these pathways will relate to the psychiatric phenomenon in question with varying degrees of coherence, ranging from utterly incoherent (like marital status) to highly coherent (like aphasias). [1]

Once we accept the above, what more do we gain by insisting that mental disorders are brain disorders? It makes some sense for neuroscientists and neuroscientifically-minded psychiatrists/psychologists. “Mental disorders are brain disorders” is an assertion that mental disorders are firmly and legitimately within the neuroscientific domain of inquiry; it is an expression of the hope that brain mechanisms involved in psychopathology will be found to be coherent and can be made tractable. But why should psychiatrists, psychologists, and social scientists—otherwise committed to the embodiment of mind and the existence of multi-level causality—prioritize the framing of mental disorders as brain disorders? We can argue in theory, as I have argued before, that one can be justified in calling a psychiatric condition a brain disorder provided we cross some empirical threshold of evidence and provided we contextualize that within a scientifically accurate view of the brain-behavior relationship, but that justification only allows people to call mental disorders brain disorders if they want to. The justification doesn’t allow us to say that everyone should prioritize calling mental disorders brain disorders; it doesn’t allow us to say that neuroscientific methods of inquiry are more scientifically privileged, more important, or more fundamental than higher-order methods of inquiry.

Language isn’t innocent. Conflicts over language are often reflections of ideological conflicts. “Brain disorder” indicates a commitment to a scientific program that privileges brain-based explanations over explanations couched in psychological and behavioral terms. This commitment can be virtuous when it exists as part of a pluralistic scientific program that makes adequate space for other approaches (the Kendlerian variety), but it can also be non-virtuous and reductionistic. And it is this latter variety that arguably has dominated psychiatric discourse, and it is this latter variety that we should guard against, and it is this latter variety that ensures that well-intentioned scientists and clinicians will continue to resist the view that we should prioritize the characterization of mental disorders as brain diseases.

[1] This point is expressed very well by Eric Turkheimer in a 1998 paper, Heritability and Biological Explanation:

“Complex human behaviors of the kind that have interested psychologists—beliefs, intentions, emotions, personalities—do not have localized biological or genetic causes in the sense that stroke lesions cause aphasia or a single gene causes phenylketonuria. What troubles social scientists opposed to biological reductionism in psychology is not simply that biogenetic theories associate behavior with genotypic or neurological variation, but rather that the biological explanations are oversimplified in that they try to explain complex behaviors as if they were aphasias. Divorce per se is unlikely to yield to neurological or genetic analysis. The difficulty is not that divorced individuals are not constituted by neurological or genetic processes, because obviously they are; the problem is that too many levels are being skipped between marital behavior and neurons or genes. Divorce is a coherent process at a social level of analysis, but it is utterly incoherent neurologically and furthermore depends for its definition on relationships with other people and institutions that do not reside in the brain at all.”

Once again, you've provided an excellent analysis. I share your concerns regarding Kendler's approach. While it represents an advancement from the metaphysical perspective, it appears to be applicable only (partially) to disorders with a high genetic risk such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, ADHD, and autism, excluding others.

Even within the high-risk categories, I'm skeptical that the known genetic variables can account for the majority of cases falling under these diagnoses. From my perspective, the genetic risk doesn't necessarily validate these categories as brain diseases but rather suggests that many diagnosed patients within these categories have psychiatric conditions where genetic variables significantly contribute to the causation process.

I think that the conceptual synthesis that you make about mental disorders is very valuable, but I do think that the categories of schizophrenia, bipolar, ADHD and autism will lead to some medical, neurobiological discoveries explaining a % of the cases, not all of them, and that those discoveries will lead to new categories, instead of validating the current ones. Think of brain imaging: it only captures macroscopic patterns, whereas the microscopic complexity of the nervous system is amazing. On the other hand, the autopsy studies are limited in terms of sample size and many confounding variables

I don't think that we should think of our current phenotypes as the end of the clinical story; instead we need to advance the clinical research to explore more precise phenotypes