Mixed Bag #13: Jonathan N. Stea on Pseudoscience and Psychology

“Mixed Bag” is a series where I ask an expert to select 5 items to explore a particular topic: a book, a concept, a person, an article, and a surprise item (at the expert’s discretion). For each item, they have to explain why they selected it and what it signifies. — Awais Aftab

Jonathan N. Stea, PhD, RPsych, is a practicing clinical psychologist and adjunct assistant professor at the University of Calgary in Canada. Clinically, he specializes in the assessment and treatment of concurrent addictive and psychiatric disorders. He’s a two-time winner of the University of Calgary’s Award for Excellence in Clinical Supervision and the 2022 recipient of the Psychologists’ Association of Alberta’s media and science communication award. He is the primary co-editor of Investigating Clinical Psychology: Pseudoscience, Fringe Science, and Controversies. His forthcoming book about mental health misinformation and pseudoscience will be published in 2025 by Penguin Random House Canada and Oxford University Press. You can follow him on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and on Substack: Mind the Science Newsletter.

Book—Scott Lilienfeld, Steven J. Lynn, and Jeffrey M. Lohr (2003). Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology. The Guilford Press.

Stea: The Preface begins, “This book is likely to make a number of readers angry.” Indeed, while threatening cherished beliefs and destabilizing worldviews are certainly not primary goals of the book, they can be a by-product. That’s because, as the Preface continues, “This book is the first major volume devoted exclusively to distinguishing scientifically unsupported from scientifically supported practices in modern clinical psychology.” Despite its potentially unsettling spotlight on clinician practices and its intimidating nature, this book was a desperately needed game-changer that sounded the alarm bells in the world of mental health services, both within and outside the discipline of clinical psychology.

Or, at least, it should have been. It was published by the Guilford Press and was popular in academic circles. It shook my perceptions of the scientific foundations of my own field and motivated my career trajectory, as I’ve been on a mission in part to further popularize and make accessible the ideas contained within to help people protect against mental health-related pseudoscience.

The book is divided into 5 broad sections that focus on discussing pseudoscientific and controversial practices in the areas of i) assessment and diagnosis, ii) psychotherapy, iii) treatment of specific adult disorders, iv) treatment of specific child disorders, and v) self-help and the media. The authors expose the widespread use of scientifically unsupported practices in these areas and plea for a tightening of our scientific reins.

Concept—The Demarcation Problem

Stea: When writing and speaking about pseudoscience, it’s important to define what it means. The question of how to draw the line between science and pseudoscience is known in the history and philosophy of science as the demarcation problem. Of course, there’s no universally agreed upon way to solve the problem, though scholars such as Sir Karl Popper and Imre Lakatos have given it one hell of a shot with their ideas of falsifiability and degenerating research programs, respectively. Other scholars, such as Larry Laudan, have even argued for “the demise of the demarcation problem” given irreconcilable differences. Progress in the philosophy of science, however, has been made.

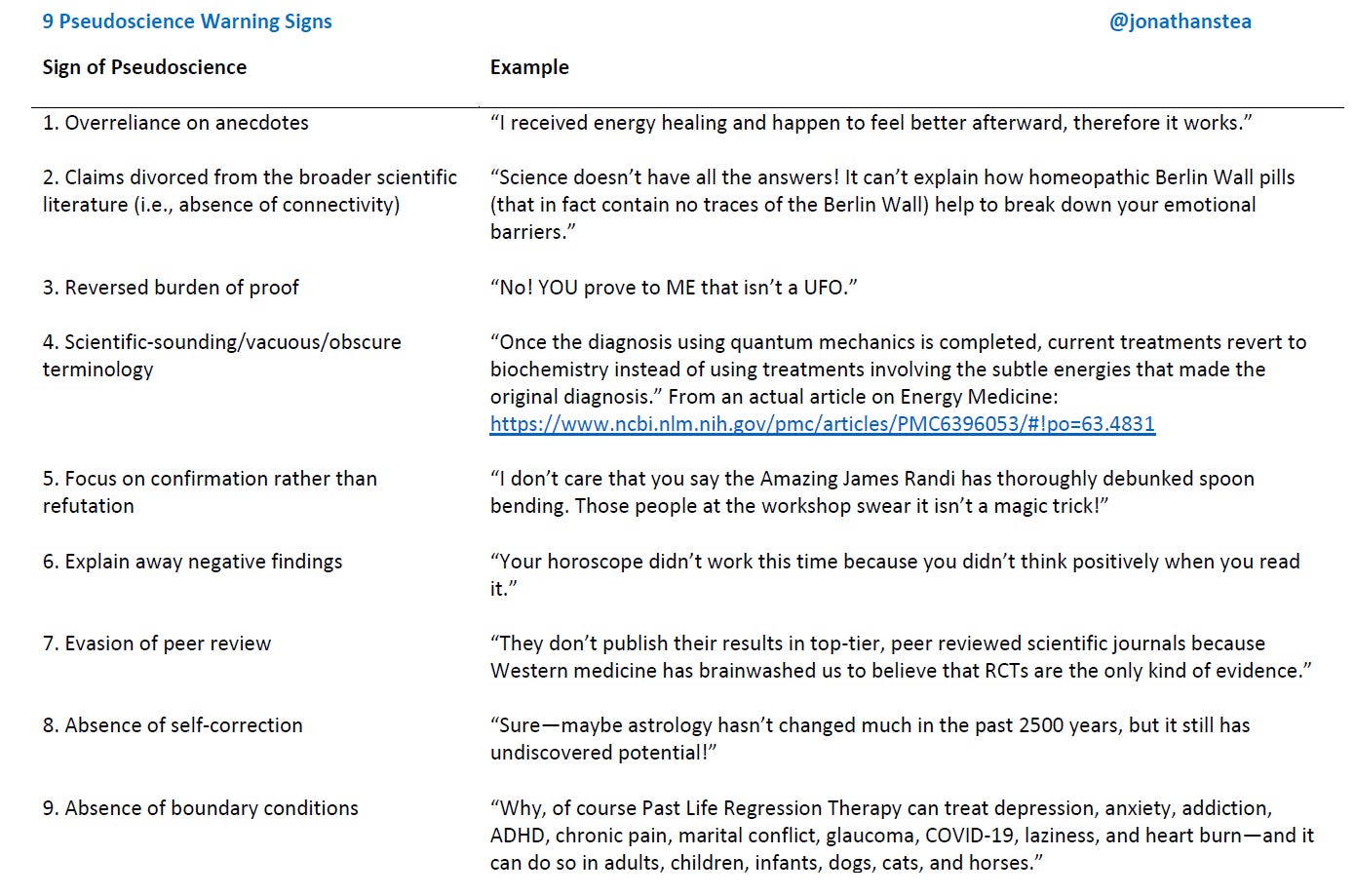

Drawing from the ideas of Massimo Pigliucci as well as Arthur Pap, Scott O. Lilienfeld and his colleagues have argued for a family resemblance perspective on pseudoscience, viewing it as an open concept with a set of useful, though fallible, indicators that can be thought of as warning signs. In this way, there’s no single criterion that draws the line between science and pseudoscience—rather, identifying pseudoscience becomes a probabilistic endeavor: the more warning signs that are present, the greater the likelihood that pseudoscience beckons our attention and skepticism when evaluating scientific health claims.

Scott O. Lilienfeld and his colleagues have argued for a family resemblance perspective on pseudoscience, viewing it as an open concept with a set of useful, though fallible, indicators that can be thought of as warning signs. In this way, there’s no single criterion that draws the line between science and pseudoscience—rather, identifying pseudoscience becomes a probabilistic endeavor…

Here are some examples:

Person—Scott O. Lilienfeld

Stea: As evidenced by now, Scott O. Lilienfeld was a giant in the field of clinical psychology and was a pioneer when it came to articulating the nature and harms associated with pseudoscience. Since the 1980s, he was outspoken about the lack of scientific rigor in psychology. A 2004 New York Times article noted that he and his colleagues have been called “assassins and parasites,” who “receive hate mail from the proponents of a variety of popular psychotherapies,” and who the president-elect of the American Psychological Association at the time had accused of “being overly devoted to the scientific method.”

Sadly, Lilienfeld died of pancreatic cancer at age 59 in 2020. His expertise expanded beyond the topic of pseudoscience to include forensic psychology and psychopathy. He authored over 350 publications, co-wrote the 2009 book 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions About Human Behavior, served as editor and chief of Clinical Psychological Science, and also served as president both of the Society for a Science of Clinical Psychology and the Society for the Scientific Study of Psychopathy. Most notably, he was renowned for his kindness and intellectual humility.

On a personal level, perhaps my biggest professional regret is that I never reached out to him to express my appreciation for his work and its impact on my development. In the context of writing my forthcoming book about mental health pseudoscience and misinformation aimed at a wide, general audience, I did reach out to his widow, Candice Basterfield, to learn more about him as a person and his legacy. In part, she described his passion for teaching scientific thinking and his hope that it would become an essential component in psychology courses.

Article—Pennycook, et al. (2015). On the reception and detection of pseudo-profound bullshit. Judgment and Decision Making.

Stea: When perusing unequivocal instances of pseudoscience, one is bound to encounter claims that are cloaked in scientific-sounding and impressive language, but that are ultimately meaningless. In other words, the claims consist of pseudo-profound bullshit, which is the term famously used by cognitive psychologist Gordon Pennycook and his colleagues in their 2015 article.

Across multiple studies, Pennycook and colleagues presented participants with bullshit statements consisting of buzzwords randomly organized into statements with syntactic structure but no discernible meaning (e.g., “Wholeness quiets infinite phenomena”). Among several findings, they notably showed that some people are more receptive to this type of bullshit than others…

Across multiple studies, Pennycook and colleagues presented participants with bullshit statements consisting of buzzwords randomly organized into statements with syntactic structure but no discernible meaning (e.g., “Wholeness quiets infinite phenomena”). Among several findings, they notably showed that some people are more receptive to this type of bullshit than others, and that those who relied more on an impulsive, intuitive style of thinking (as opposed to an analytical style) were more likely to consider bullshit statements as profound. They even showed that participants had difficulty distinguishing between pseudo-profound bullshit statements and the Twitter feed of Deepak Chopra. For their efforts, they were awarded an Ig Nobel Prize in 2016. In his acceptance speech, Pennycook thanked Chopra and Dr. Oz, along with other personalities, politicians, tobacco lobbyists, climate-change deniers, and creationists, noting, “Your quantum vibrations permeate the transcendent essence of true experience that coalesced into our bullshit … paper.”

Facetiousness aside, the article is emblematic of the current misinformation crisis in which we currently find ourselves and speaks to the importance of protecting ourselves against pseudoscience in part by cultivating analytical thinking.

Surprise Item—The Wellness Industry

Stea: I’ve chosen the wellness industry as my surprise item because, perhaps unsurprisingly, it is home to the biggest purveyor of mental health pseudoscience in our culture. The modern wellness industry itself is largely unregulated and valued at $4.5 trillion globally. It includes some legitimate sources of health (e.g., sports and exercise classes), but also the alternative medicine industry, which is estimated to be worth $200 billion globally by 2025.

Alternative medicine captures crystal clear pseudoscientific approaches, such as homeopathy, energy medicine, naturopathy, chiropractic, Ayurveda, and guru-led self-help, among so much more. Sometimes these approaches are delivered without any accountability to patient care under legally unprotected titles (depending on particular countries and jurisdictions), such as “therapists,” “counsellors,” and “coaches.” Other times, these approaches are paraded under the marketing brands of “complementary and alternative medicine (CAM),” “integrative medicine,” and “functional medicine.”

Psychologists have an ethical duty and responsibility to society to promote and practice evidence-based patient care. Part of that mission involves the converse, which is teaching people how to identify and protect themselves against pseudoscientific misinformation and practices. This ethical duty is the inspiration for my science advocacy work, and it necessarily involves shining a light on the harms of the wellness industry. I plan to continue these efforts and hope that you’ll join me.

See previous posts in the “Mixed Bag” series.

What a surprisingly pleasant read, and a wonderful tribute to Scott Lilienfeld.