Mixed Bag #18: Courtney Thompson on Phrenology

“Mixed Bag” is a series where I ask an expert to select 5 items to explore a particular topic: a book, a concept, a person, an article, and a surprise item (at the expert’s discretion). For each item, they have to explain why they selected it and what it signifies. — Awais Aftab

Courtney E. Thompson, PhD is Associate Professor of History at Mississippi State University. She is the author of An Organ of Murder: Crime, Violence, and Phrenology in Nineteenth-Century America (Rutgers University Press, 2021). Her current research focuses on emotion in the doctor-patient relationship in the late nineteenth century.

For a quick primer on phrenology, see her essay on phrenology here in the Encyclopedia of the History of Science.

Concept—Pseudoscience

I want to start with a concept because I think this is key to understanding my point of view on phrenology and its history, especially how I hope to disrupt common conceptions of this practice. Specifically, I want to address my enduring bugbear, which is the concept of “pseudoscience,” a term which I argue, here and elsewhere, should not be applied to phrenology. “Pseudoscience”—a term which is used to refer to practices of knowledge production understood to be nonscientific—is not a useful term, in general, for thinking about the history of science. With regard to phrenology, its association with this concept has two pitfalls that can lead both historians and laypeople astray, contributing to large misconceptions about phrenology.

First, thinking of phrenology as a pseudoscience is ahistorical, as phrenology has its roots in scientific theories and practices that were widely accepted as science in the period in which it was developed. Its earliest theories and proponents, German physician-anatomists Franz Joseph Gall and Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, were traditionally trained and credentialed, recognized as legitimate (and respected) practitioners by their scientific peers. While phrenology’s precepts were controversial, the early debates of the 1810s and 1820s around this science were, as noted historians of science (including Steven Shapin, Roger Cooter, and Geoffrey Cantor), often staged as commentaries on the standards of science itself. In effect, debates about phrenology were debates about science, which enables phrenology to serve as a key example for how scientific communities and consensus were built (and broken) at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Moreover, the early adopters of phrenology, in addition to scientists and physicians, tended to be members of the intellectual and political elite, both in Europe and in the United States, who flocked to the science because of its perceived value as elite science. To refer to phrenology as “pseudoscience” erases these origins and this history. Just because the practice was eventually discarded by scientists does not mean that it was never considered to be a “real” science.

Second, framing phrenology—or any discarded scientific practice—as “pseudoscience” allows people in the present to distance themselves from the past, contributing not only to teleological understandings of science, but also a kind of willful blindness to the long tail of such theories. As I explore in my book (An Organ of Murder), phrenology, among other things, contributed to nineteenth-century theories about criminal minds and types, which continue to shape how we expect criminals to look and the language we use to explain criminal behaviors. Phrenology was used throughout the nineteenth century to validate social inequities, to justify practices like slavery and imperialism, and to naturalize qualities of mind and behavior. Many of the premises of phrenology are still with us—or are constantly being “rediscovered,” often by AI enthusiasts trying to use machine learning to judge and categorize people based on facial shapes. Referring to phrenology (or eugenics, to take another example) as “pseudoscience” makes it easy to dismiss these scientific practices as nonsense, which thereby paradoxically enables them to perpetuate (and cause harm) in the present.

Framing phrenology—or any discarded scientific practice—as “pseudoscience” allows people in the present to distance themselves from the past, contributing not only to teleological understandings of science, but also a kind of willful blindness to the long tail of such theories.

Book—Roger Cooter, The Cultural Meaning of Popular Science: Phrenology and the Organization of Consent in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge University Press, 1985).

To a large extent, my arguments about phrenology’s impact are not new. Phrenology has been very well studied by historians of science and medicine. Indeed, key texts and debates occurred among historians in the 1970s and 1980s about the nature of phrenological theories, practices, and especially the structures of phrenological debates and communities. One notable work that set the stage for taking phrenology seriously as science was Roger Cooter’s The Cultural Meaning of Popular Science (1985). Cooter’s book is an exercise in how to study science itself. Rather than treating phrenology like a joke or oddity, the way many other historians and commentators did before (and after) him, he instead made an elegant case for considering phrenology as science and thinking through its value as a case study for understanding the relationship between science, society, culture, and politics. Cooter’s book has its limitations—it is focused on Great Britain, and has little to say about gender or race, for example—but it is an essential starting point for entering both the history and the historiography of phrenology.

Articles—Carla Bittel, “Testing the Truth of Phrenology: Knowledge Experiments in Antebellum American Cultures of Science and Health,” Medical History. 2019.

&

James Poskett, “Phrenology, Correspondence, and the Global Politics of Reform, 1815-1848,” The Historical Journal. 2017.

If Cooter’s approach was significant for locating phrenology within the history of science, other scholars in the past four decades have attended to themes and questions that he neglected, especially around race, gender, and colonization. I’m going to suggest two articles (I’m cheating a little bit!) to suggest how far the field has come and how much broader our understanding of phrenology, its users, and its impact on science and society has become. First, Carla Bittel has written extensively on gender and phrenology, focusing on women as users of phrenology, as well as the complex relationship between the popular user and the science. In particular, I recommend her 2019 essay, “Testing the Truth of Phrenology,” which complicates our understanding of phrenology as a popular science, demonstrating how users experimented with phrenological practices and theories, testing phrenologists and themselves. This essay rethinks the “popular” aspects of this science and challenges the simplicity of narratives of popularization, demonstrating the active roles of users (considered with attention to class, race, and gender) in perpetuating and shaping phrenology in nineteenth-century America. Second, James Poskett’s work has paid close attention both to the material culture of phrenology and the global (and especially imperial) impacts of the science. In his essay, “Phrenology, Correspondence, and the Global Politics of Reform, 1815-1848,” he discusses phrenology as a “global political project,” returning to the question of phrenology as a reform science that animated 1970s debates. Here, he explores how phrenology was used as a tool of global reform movements, as he demonstrates through close reading of early nineteenth-century correspondence.

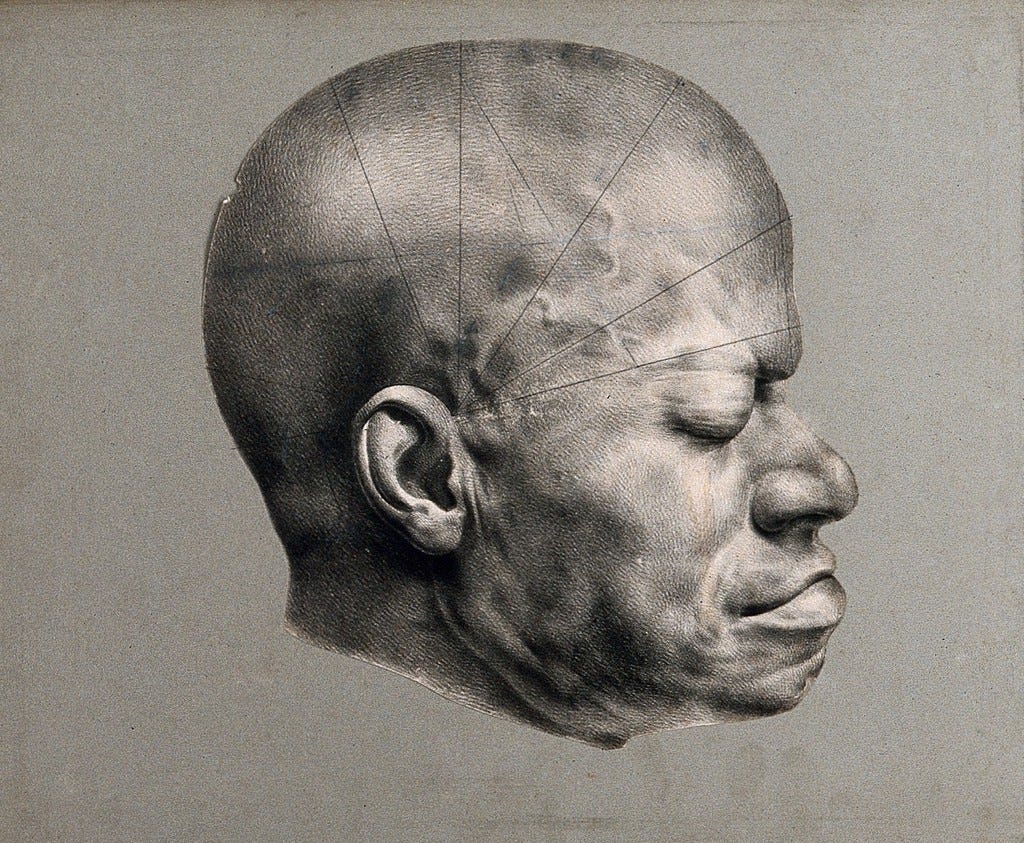

Person—Eustache

I do not want to fall into the “great man” trap by selecting one of the founders of the discipline, or one of the more famous phrenological popularizers. Instead, I want to highlight here a key phrenological subject, about whom much was written in the nineteenth century. Eustache was an enslaved Black man who purportedly saved his white enslaver during the Haitian revolution. Eustache was held up as a key exemplar by phrenological writers throughout the nineteenth century; specifically, his skull was used as an example of the organ of Benevolence, with illustrations emphasizing this portion of his skull. The use of this example, moreover, spoke to racialized expectations about skull shape as it related to behavior. Eustache’s act of saving his enslaver, as well as other discussions of his character, indicated that his nature was that of a perfect servant—or rather, a perfect slave. Eustache was used as an example of an exemplary Black individual by virtue of his devotion to his enslaver, and thus used as further justification for the “natural” status of people of African descent for slavery. While many phrenologists were abolitionists and spoke out in favor of abolition, phrenological theories and examples were nevertheless frequently mobilized in favor of slavery, or, at least, as evidence of the “natural” superiority of the white race over all other groups. Eustache is just one example of how the heads of Black (and non-white) individuals were used as evidence and justification for their own continued disenfranchisement and the naturalization of racial hierarchies.

While many phrenologists were abolitionists and spoke out in favor of abolition, phrenological theories and examples were nevertheless frequently mobilized in favor of slavery, or, at least, as evidence of the “natural” superiority of the white race over all other groups.

Surprise Item—The Skull

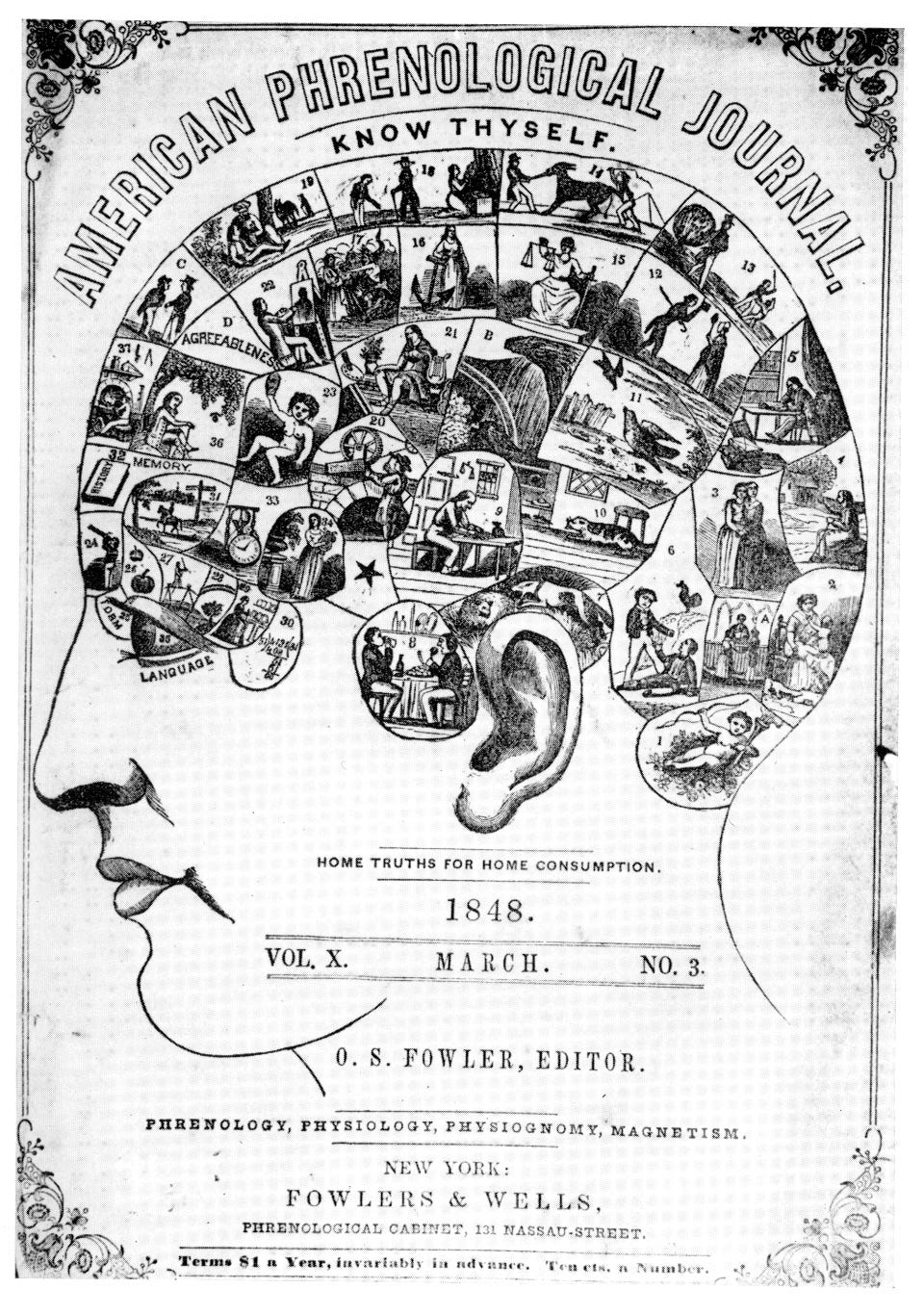

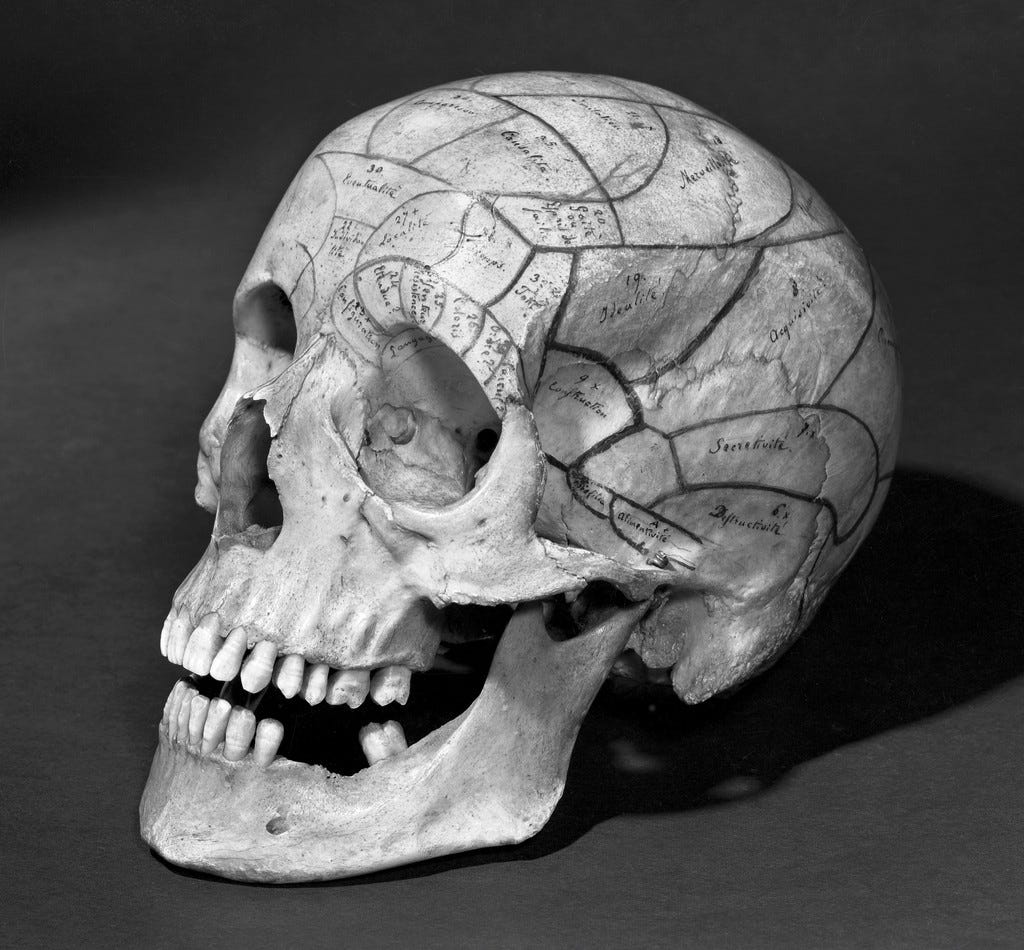

I thought quite a bit about this category, because phrenology is a science that is rich in material objects, both historical and postmodern (one can buy any number of phrenologically inspired décor on Etsy, for example). But I thought it made sense to focus on one of the classic objects of phrenology, the skull, especially since there is ongoing debate as to what to do with the many skulls that had originally been part of phrenological cabinets and are now in museums and archives.

Phrenologists collected many kinds of material evidence of the body—casts of the head, both before and after death, and, when they could get them, actual skulls of the dead. These objects were used in phrenological lectures for both elites and laypeople, and they were frequently displayed as part of a phrenologist’s cabinet. The image of the phrenologist (or physician, or anatomist, for that matter) with a skull is a common one in both visual culture and in our mental image of what phrenology looks like.

But where did these skulls come from? It should not surprise you to learn that most of those skulls that ended up in phrenological cabinets were those of executed criminals, the indigent poor, enslaved people, or Indigenous people. These skulls were often taken from graves or from the autopsy table without the consent of the individual, their family, or their descendent community (especially in the case of Indigenous skulls). The ways in which these skulls were acquired were marked by violence, empire, and white supremacy. And many of these ill-gotten remains are on display in the present.

This fact has animated recent debates about what to do with collections of human remains, including those acquired by nineteenth-century phrenologists and contemporaneous racial scientists. Nineteenth-century racial anthropologist Samuel George Morton’s collection of 1300 skulls, held by the Penn Museum, for example, has in recent years taken on a project of repatriating Indigenous skulls and burying those of Black Philadelphians (though controversy and debate is ongoing). Also in Philadelphia, the Mutter Museum is currently considering the display of the Hyrtl collection of 139 skulls, which remains on public display, though the institution is in the process of redeveloping its displays (which is also causing current controversy). Ultimately, as I have argued elsewhere, I believe that such human remains, which lack provenance and proof of informed consent for research and display, should not be displayed publicly and should be returned to descendant communities whenever possible. Moreover, we should also attend to the origins of skulls, skeletons, and other human remains held by individuals and institutions. Even if a skull was never part of a phrenological cabinet, the acquisition of skulls (and human remains more generally) should not be black boxed, but instead considered carefully as an ethical component to the stewardship and display of human remains.

See previous posts in the “Mixed Bag” series.

Great point about pseudoscience and the history of science. It's dangerous to think of ourselves as smart, unlike the stupid people of the past, or think there's always some clear and bright line between science and pseudoscience that smart present-day people can spot.