Notable Links & Miscellanea - April 20, 2024

Conceptual competence, psychoanalysis, origins of neurodiversity, and more

I have a new paper out in BJPsych Bulletin — Conceptual competence in psychiatric training: building a culture of conceptual inquiry — with John Sadler, Brent Kious, and G. Scott Waterman as co-authors. This is based on a symposium session we presented at 2023 Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, and builds on my earlier work with Waterman on conceptual competence. It’s open-access and will be of interest to psychiatric educators.

“Building a culture of conceptual inquiry in psychiatric training requires the development of conceptual competence: the ability to identify and examine assumptions that constitute the philosophical foundations of clinical care and scientific investigation in psychiatry. In this article, we argue for the importance of such competence and illustrate approaches to instilling it through examples drawn from our collective experiences as psychiatric educators.”

I was interviewed by the Carlat Psychotherapy Report on how philosophy of psychiatry can inform clinical practice. We touch on a number of different issues. Here are some quotes:

CPTR: A hotly debated topic these days is whether mental disorders constitute diseases, disorders, syndromes, or—to borrow a term from Szasz—problems in living. Can you tell us briefly where you stand on this issue?

Dr. Aftab: It’s a complicated debate. Philosophers of biology tend to think of disease/disorder in terms of a failure of (evolved) biological mechanisms. That is, different organs of the body have been naturally selected to carry out certain tasks, and if there is a breakdown or disruption in one’s ability to carry out that task, it is considered a dysfunction. This position gets murky in psychology and psychiatry because our scientific understanding of the evolution of mental functions is very primitive. It may also be the case that many psychiatric conditions don’t involve breakdowns of evolved functions; rather, they may represent extreme states on a continuum of intact functions (eg, high neuroticism). They may involve evolutionary design-environment mismatches (eg, hyperactivity in a modern school environment). They may even be products of maladaptive learning with otherwise intact learning mechanisms (eg, psychological sequelae of growing up with childhood neglect).

CPTR: Interesting. So, what are mental disorders then? Are they medical diseases?

Dr. Aftab: Mental and medical disorders do not have one unique feature that all conditions share and that differentiates them from nondisordered conditions. What they share is a cluster of overlapping characteristics, such as inflexibility, atypicality, irrationality, maladaptivity, chronicity, distress, disability, harm, and impediments to well-being. The question of whether a psychological problem is a disorder or a “problem in living” is inconsequential on its own; it doesn’t matter, as long as we recognize that the problems in question benefit from clinical care and require scientific study for a better understanding of their nature. If we agree that a problem requires a clinical solution, whether you call it a disorder or a problem in living is simply semantic. The view held by Szasz and his followers, however, is that if something is a “problem in living,” then it is outside the purview of medicine; medicine has no authority over it or no justification to treat it. It is this assumption that I disagree with. This is not how medicine and psychology work. The Szaszian view fundamentally misunderstands what justifies clinical care.

CPTR: Could you describe a real-world scenario where a therapist’s lack of philosophical clarity hampered the therapeutic process? How might a clearer philosophical stance have altered the outcome?

Dr. Aftab: Some therapists have an overly reductive understanding of psychiatric diagnosis. They seem to think a diagnosis of mental disorder necessarily implies there is some intrinsic brain abnormality. They think if someone’s symptoms can be explained with reference to a history of abuse or trauma, then a diagnosis doesn’t apply to them. The logic is so incoherent that it’s amazing that anyone believes it, but I’ve encountered many therapists who believe some version of it. They think you can’t diagnose depression, bipolar disorder, or a personality disorder, if their symptoms are “understandable” as a response to some sort of psychological injury. But psychiatric diagnoses are descriptive characterizations, compatible with a history of abuse or trauma, or the putative “understandability” of symptoms, and if we miss the appropriate descriptive characterization, we can deprive a patient of treatment options they can benefit from.

Paul Bloom ( Paul Bloom) has responded on his Substack to my discussion of two chapters from his book Psych: The Story of the Human Mind with his characteristic generosity (see here and here for my posts). He focuses in particular on the discussion of falsifiability in psychoanalysis. I am broadly in agreement with what Bloom says here, and in contrast to the book chapter, Bloom seems to recognize that psychoanalytic hypotheses in the clinical context can be tentative and receptive to counter-evidence, but the concern is:

Aftab writes about a psychotherapist’s views about a patient, saying that a hypothesis like father hatred “would likely be endorsed in the beginning with a low degree of confidence. And the psychotherapist would ideally be receptive to verification or falsification based on what the patient says in response and what is observed subsequently in psychotherapy.”

My worry is that a lot rests on the term “ideally.” I agree that this is ideal; my concern is that it isn’t what tends to really happen. To make things worse, certain core ideas of psychoanalytic theory, such as the notion that patients can be resistant to insight, make falsification especially difficult, though not impossible.

I share these worries as well. Perhaps I can state the matter as follows: It is not the case that psychodynamic hypotheses in the context of individual psychotherapy are unfalsifiable. It is rather that the prospect of falsifiability is extremely fragile, such that any amount of dogmatism on the part of the therapist can easily derail the process.

Kemtrup raises the point on X/Twitter that sometimes the purpose of psychoanalytic interpretations in psychotherapy contexts is not to demonstrate their absolute truth but to facilitate a pluralistic understanding of oneself:

“Sometimes the pt and analyst/therapist explore things similar to what gets described in science as “underdetermination of theory by evidence” wherein two or more explanations equally fit with the available case history, facts about the pt. And the pt can BENEFIT from understanding that he can be understood in more than one way, and humility is felt as a virtue, which opens up possibilities for new ways of thinking, acting, and feeling. Often, a sign of health in a patient is that they start to understand themselves pluralistically, through multiple lenses. “I suppose one way to think about what I did is this, but another is this. I don’t really know which is true at the moment.” That’s the equivalent of what Fonagy calls “mentalization,” the ability to have complex, epistemically humble, pluralistic understandings of what goes on in other people’s mind, instead of simple certain things like “she must hate me and for no reason.” It’s mentalization but of one’s OWN mind, which goes hand in hand with mentalizing others and forming better relationships, self reflection, self control, autonomy, an integrated view of one’s self and others, etc.”

A fitting complement to the discussion above: Michael Bacon wrote in Aeon about his “dismal years in psychoanalysis” with Edna O’Shaughnessy, a leading child psychoanalyst, and that reading what she wrote about him was even worse. He writes: “She could perceive me only as a device to play out already fixed ideas,”

“O’Shaughnessy insists that the objectivity of psychoanalysis is vouchsafed by the analyst undertaking ‘supervision and discussions with colleagues’. Those colleagues, however, already share the analyst’s doctrine, and what they discuss on any given day will consist entirely of what she chooses to tell them in the shared idiom. The whole company might as well be a circle of astrologers.”

Dan Williams ( Dan Williams ) has produced one excellent post after another on his Substack “Conspicuous Cognition.” I particularly enjoyed the following: Can democracy work?; People are persuaded by rational arguments. Is that a good thing?; and The media very rarely makes things up

An intriguing new paper in Lancet Psychiatry by Clara Humpston and Todd Woodward — Soundless voices, silenced selves: are auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia truly perceptual?

“A typical question during clinical assessment is asking whether the voices that a person hears sound identical to the way the clinician's voice is heard. In this Personal View, we argue that the most important factor in auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia spectrum psychoses is a loss of first-person authority, and that a perceptual quality is not required for it to be this kind of hallucination. We draw on evidence from cognitive neuroscience showing that the activation of brain networks retrieved during capture of auditory verbal hallucinations that were experienced when a patient was in a functional MRI scanner does not match activation of networks retrieved during auditory perception. We propose that, despite early writings by Esquirol and Schneider that defined auditory verbal hallucinations as beliefs in perception rather than true perception, cognitive neuroscience, psychiatric training and practice, and patients adopting clinical vocabulary have been strongly influenced by the progression of the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, which increasingly place emphasis on language, such as the “full force” of a true perception.”

“We, an international group of autistic scholars of autism and neurodiversity, discuss recent findings on the origins of the concept and theorising of neurodiversity. For some time, the coinage and theorising of the concept of ‘neurodiversity’ has been attributed to Judy Singer. Singer wrote an Honours thesis on the subject in 1998, focused on autistic activists and allies in the autistic community email list Independent Living (InLv). This was revised into a briefer book chapter, published in 1999. Despite the widespread attribution to Singer, the terms ‘neurological diversity’ and ‘neurodiversity’ were first printed in 1997 and 1998, respectively, in the work of the journalist Harvey Blume, who himself attributed them not to Singer but rather to the online community of autistic people, such as the ‘Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical’. Recently, Martijn Dekker reported a 1996 discussion in which one InLv poster, Tony Langdon, writes of the ‘neurological diversity of people. i.e. the atypical among a society provide the different perspectives needed to generate new ideas and advances, whether they be technological, cultural, artistic or otherwise’. Going forward, we should recognise the multiple, collective origins of the neurodiversity concept rather than attributing it to any single author.”

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has an updated entry on the Neuroscience of Consciousness.

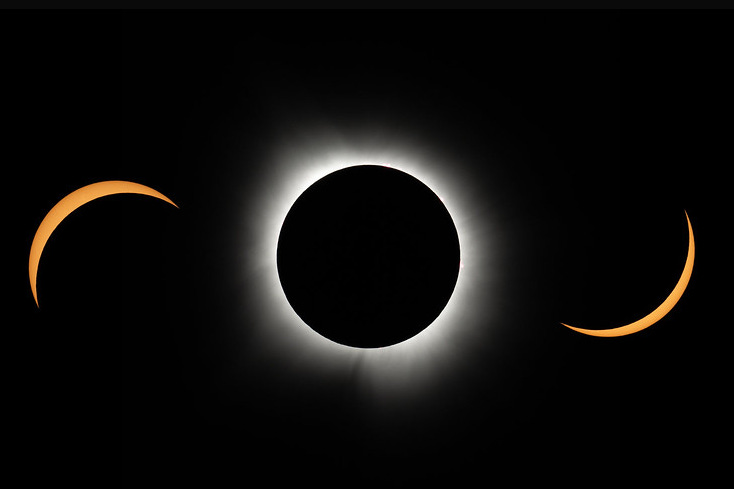

After watching the total solar eclipse on April 8, I really enjoyed reading Justin Smith-Ruiu’s post Fear the Eclipse: “… it’s damned hard to account for the religious sentiment that accompanies rare natural phenomena when we lack the conceptual frame and vocabulary of any religious tradition to put this sentiment into words.”

Too Mad to be True III - The Paradoxes of Madness conference will be held on October 30-31, 2024, in Ghent (Belgium) and online. Abstracts for presentation are being invited. (Josh Richardson reviewed ‘Too mad to be true II - The promises and perils of the first-person perspective’ for Psychiatry at the Margins last year.)

Sofia Jeppsson reviews John Sadler’s latest book, Vice and Psychiatric Diagnosis

“… an overarching theme of the forty final theses is to ditch the attempt to find a neat mad/bad divide. Psychiatry should admit and discuss more explicitly than has hitherto been the case how value-laden it is, and how value-laden it must be. An open discussion allows for scrutiny and criticism of underlying values, instead of implicit acceptance.”

A research letter in JAMA reports on Industry Payments to US Physicians by Specialty and Product Type from 2013 to 2022. Neurologists and psychiatrists (pooled together) are #2 after orthopedic surgeons in terms of total amount received (perhaps inflated due to combining the two specialties), but here’s the interesting part: the amount paid to the median neurologist/psychiatrist is a whopping $32, with bulk of the money going to the top 0.1% of physicians. Among the top 25 drugs related to industry payments, only 3 were psychiatric medications: Vraylar, Latuda, and Abilify.