Psychiatric Diagnosis and the Endgame of Validity

From Validators to Utilitators

“the events, procedures and results that constitute the sciences have no common structure; there are no elements that occur in every scientific investigation but are missing elsewhere… Successful research does not obey general standards; it relies now on one trick, now on another; the moves that advance it and the standards that define what counts as an advance are not always known to the movers.

… if scientific achievements can be judged only after the event and if there is no abstract way of ensuring success beforehand, then there exists no special way of weighing scientific promises either…” (italics in original)

Paul Feyerabend, Against Method. Introduction to the Chinese Edition

Two excellent philosophical papers trace the history of validity in psychiatric classification, examine the present landscape of validators and frameworks, and offer a glimpse of what may lie ahead:

Miriam Solomon’s (2022) “On Validators for Psychiatric Categories” in Philosophy of Medicine and Nicholas Zautra’s (2025) “Psychiatry’s New Validity Crisis: The Problem of Disparate Validation” in Philosophy of Science.

These articles are full of delightful nuances, historical as well as scientific, and I highly recommend them.

The idea of “validity,” as it exists in psychiatric classification, is about whether diagnostic categories latch onto real attributes of psychopathology. This is sometimes understood as correspondence to disease entities (or natural kinds), sometimes understood as the existence of real, distinct syndromes, or sometimes generally as evidence that symptom groupings are not arbitrary but provide clinically relevant predictive information. The field often slides between talk of “validated” (supported by evidence) and “valid” (true or real), and the latter is an idealization we should treat cautiously.

Utility, in contrast, is about usefulness. Does a category help with clinical care (communication, prognosis, treatment), research planning, prediction, education, billing, or policy? Because a diagnostic category cannot really be useful in many of these domains without capturing, at least, clinically relevant predictive information, there is an overlap between validity and utility, and because we talk about validity in rather confusing ways, sometimes folks talking about validity are actually talking about utility, and sometimes folks talking about utility are actually talking about validity.

A validator is a line of evidence used to judge a diagnostic category, e.g., family aggregation, course of illness, biomarkers, response to treatment, and so on. The classic logic is that if multiple validators point in the same direction (“converge”), the category is not just a bag of symptoms but a coherent syndrome that is supported by scientific evidence and that, in turn, supports clinical prediction.

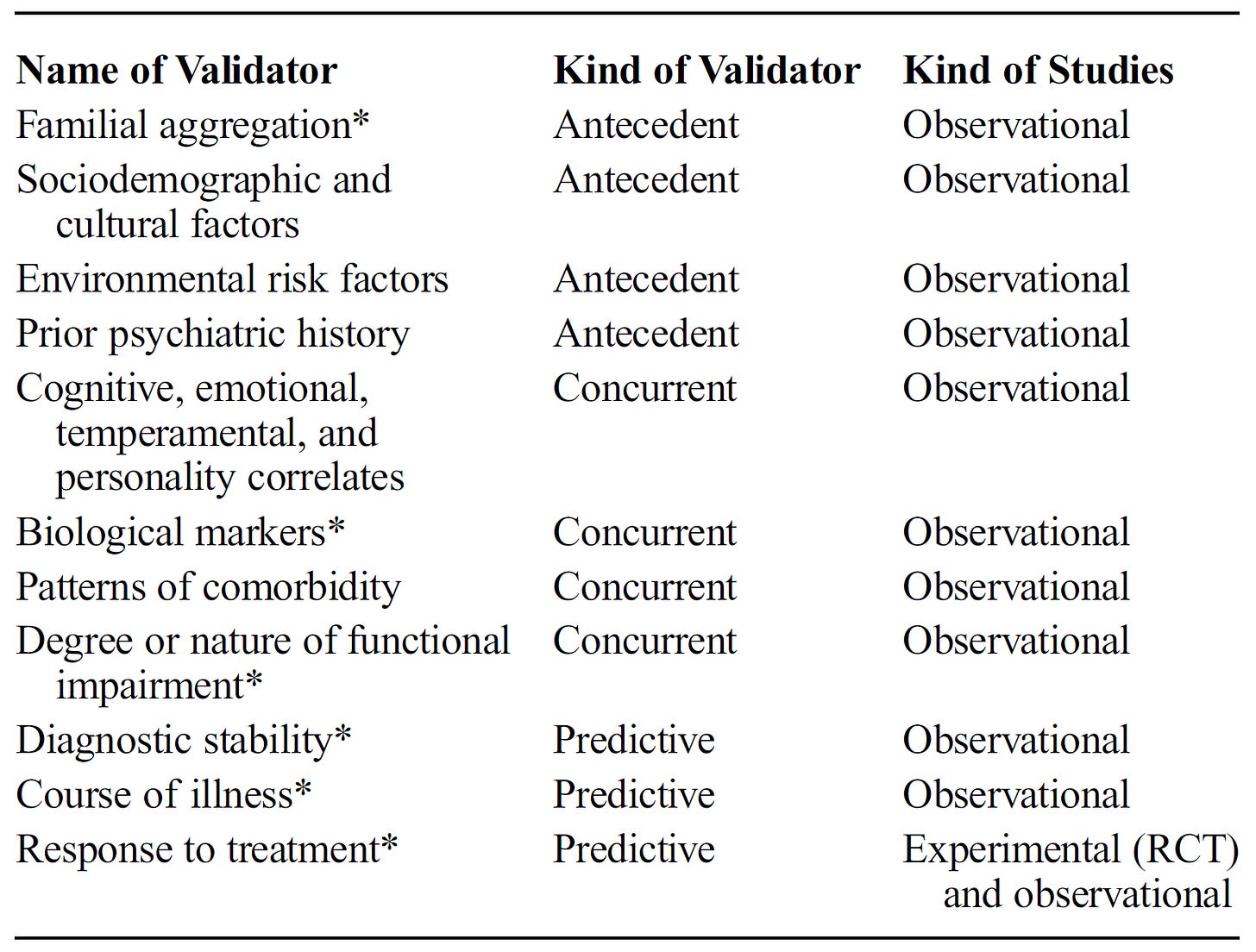

The DSM-5 Steering Committee lists 11 validators, with several labeled high priority:

These ideas about validity go back to Robins and Guze (1970) and the groups of neo-Kraepelinians at Washington University in St. Louis. The Washington University group introduced operational diagnostic criteria (Feighner criteria) and a five-part validating method: clinical description, lab studies, differentiation from other disorders, follow-up, and family studies. They used the term “phases.” Kenneth Kendler expanded the list to eight validators in the 1980s by adding precipitating factors, response to treatment, and diagnostic consistency over time, and was probably the first to use the term “validator” in this context. Kendler later recognized that validators may not align and that empirical evidence may point in different directions. He suggested openly using values to guide decision-making when evidence is not decisive.

Over time, genetics, neuroscience, and clinical data failed to converge on a single picture, fueling a crisis of validity by the time DSM-5 (2013) was published. Expected “zones of rarity” between disorders often aren’t found; “otherwise/unspecified” categories are heavily used; thresholds for crossing from variation to disorder are uncertain. Biomarkers and genetic associations are nonspecific. Heritability is common, but specific genes and biomarkers seldom map neatly to DSM categories. By and large, available treatments for mental disorders are nonspecific, and medications and psychotherapies work across many categories. People with the same diagnosis may share few symptoms; high comorbidity hints at deeper causal connections. All this undercuts the idea that categories track distinct causal mechanisms.

Different validators point in different directions, and there’s no standardized, defensible method for weighting them; some validators are designated “high priority” by the DSM steering committee without published justification. Most validator evidence is observational or basic-science style, not RCT-based, so standard meta-analytic tools don’t neatly apply, making principled aggregation difficult.

To be clear, DSM categories have non-trivial and meaningful validator evidence; DSM symptoms are not arbitrary, and they offer imperfect but non-zero predictive value and clinical guidance. However, DSM diagnoses do not correspond to distinct disease mechanisms, etiologies, essences, or natural kinds. This is what people generally mean when they say that DSM categories are not valid; this is also, unfortunately, easy to misunderstand (especially by polemical critics) as the assertion that DSM categories are not supported by validators or that they have no meaningful clinical utility.

What are alternatives to a central focus on validity? Solomon proposes giving more explicit weight to reliability, clinical utility, and harm avoidance when revising DSM categories, while maintaining institutional memory so that categories can be re-revised as new evidence appears.

Solomon also introduces the term “utilitators” as an analogue of “validators”:

“Utilitators would include the traditional validators (which are associated with predictive and research utility) but go beyond them to include all kinds of utility. Including all relevant utilitators complicates the practical task of aggregation of considerations relevant to classification. This is because rather than the two traditional goals of the DSM—reliability and validity— there are multiple kinds of utility, some of which are independent of others… Utility is a broader concept than validity, perhaps broad enough (when generously construed) to include all the reasons for or against a particular diagnostic category.” (Solomon, 2022)

The multiplication of new frameworks beyond the DSM, such as Research Domain Criteria, Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), network models, and predictive-processing approaches, etc., is portrayed by Solomon as a healthy response to the validity impasse, and I agree. These approaches question the DSM presumption that syndromic categories best individuate disorders, and they organize evidence differently. However, because of these developments, DSM’s crisis of validity is already old in a sense. Zautra argues that the new crisis is the problem of disparate validation. Alternative programs—Zautra focuses on HiTOP, symptom network models, and RDoC—have each developed their own standards for what counts as valid. Because they disagree about the phenomena being classified, what evidence counts, and what “validity” even is, attempts at a single, unified validation break down. It’s difficult to compare frameworks, to align or integrate them, and to define a common concept of validity across them.

As a minor aside here, I wasn’t quite clear on this issue, and I was glad to see Zautra clarify the matter: although some prominent writers have equated DSM “diagnostic validity” (based on Robins & Guze validators) with “construct validity” (used in psychological testing and psychometrics), Zautra shows they’re not the same. Historical proposals to import psychometric validity (content, criterion, convergent/divergent, etc.) into DSM were never adopted; influential figures (e.g., Kendell) explicitly tied diagnostic validity to predictive power and clinical utility rather than to psychometric theory.

In the context of the problem of disparate validation, Zautra advises the field to embrace interactive pluralism and not seek forced unification. Zautra says: stop chasing a single, merged notion of validity. Let distinct frameworks proceed in parallel, openly critique each other, and pressure-test their own standards. Each framework should make its terms, measurement conditions, and preferred paradigms explicit, build consistency, and outline the values shaping decisions.

Zautra suggests reconsidering the special epistemic status we give to validity and validators until the within-framework standards of evidence are fleshed out and steadier. As a provisional cross-framework comparator, the field can develop utility standards (e.g., predicting course and response to treatments), using Solomon’s “utilitators” such that utility becomes a shared, pragmatic yardstick.

“Lastly, I recommend psychiatry strongly reconsider the high epistemic value its frameworks currently place on the concept of validity. Only once we’ve begun to stabilize validity within each framework—allowing psychiatry to get a hold on its disparate validation procedures—may validity have its special status returned. As a provisional attempt to integrate across disparate concepts of validity, I recommend developing and utilizing standards of utility. Utility is collectively thought of as a “graded characteristic that is partly context specific” (Kendell and Jablensky 2003, 9) and more broadly applicable as the degree to which a psychiatric classification may predict “course, outcome, and likely response to available treatments, even if their inner biological and psychological structure is not fully understood” (Jablensky 2016, 26). As it turns out, just as the concept of utility was all-important for diagnostic validity within the original Kraepelinian formulation and in that of the DSM, each of the other conceptions of validity across HiTOP, the Network Approach, and RDoC also align with the Kraepelinian tradition of treating utility as a primary validator. To this end, I recommend a moderate convergentist approach, which implies we may partially reduce utility to a shared conception that focuses on shared similarities between frameworks.” (Zautra, 2025)

I started this post with some quotes from Feyerabend. Feyerabend’s point is that there’s no context-free recipe for scientific progress. Success arrives through methods that fit a particular problem, tradition, and stage of inquiry, not through a universal checklist that guarantees good science ahead of time. Psychiatry’s validity debates echo this on several fronts.

The field has tried to treat “validators” as if a convergent set would certify a diagnosis as real. Fifty years in, the evidence is mixed and conflicting. There is no procedure of validity, detached from specific questions and contexts, that ensures success.

It is curious that general medicine does not struggle with the issue of validity in the same way. Medicine, of course, employs all the validators currently used by the DSM, but they are not really described in these terms, and as far as I know, “validator” talk is rather unique to psychiatry among medical specialties. In most of medicine, physiology provides a stable anchor that psychiatry lacks. Our diagnoses are built from elusive things, from patterns of reported experiences and observed behavior. “Do our symptom configurations track other information of interest to us?” is an important and legitimate question, and points of evidence such as family history, course, treatment response, physiological associations, etc. are reasonable answers, but I think we got confused along the way.

It was worth considering whether disease entities or biological essences are lurking behind psychiatric syndromes; we searched and came up empty-handed. The science of psychopathology now faces the same challenge confronted by any other science: developing good explanations of the phenomena of interest, hopefully ones that allow for improved prediction and control. There exists no special recipe to accomplish that, except the creative, grueling work of science. The Robins-Guze-Kendler validators, or utilitators if you prefer, are fine. Good enough. I don’t have any objection to their use. But I do wonder if this wish to characterize transitory, descriptive constructs as valid (instead of useful) in the absence of an adequate causal-mechanistic-theoretical understanding is naïve, if not impossible.

See also:

In my view the set of mechanisms that cause most mental illness are already well-established, but for some reason aren’t commonly all put together or popular. I’m very curious for people’s thoughts, especially on what fraction of mental illness this model describes.

Most cases of mental illness are individually unique complex adaptive system attractor states whose reinforcing elements are something like:

1. Learned (predictive processing) bayesian priors (e.g. a belief like “I am bad” associated with a fear response that drives thought and behavior) that emerged as an adaptive response to a different context than the individual is currently in. The different context is often an emotionally dangerous childhood, which often result in sets of priors that we call things like “attachment disorders.”

2. Attention (predictive processing) and its lack (avoidance). Incoming sensory evidence is typically sufficient to update (called reconsolidation in memory research) priors that are no longer adaptive, but that only works when the strength (how much attention is payed to it) of the sensory evidence is within some range of the strength of the prior. So it fails when there isn’t sufficient attention to the sensory evidence or when the strength of the prior is too high.

3. Priors predicting certain levels of threat and powerlessness activate the set of autonomic nervous system functions called the defense cascade, i.e. sympathetic/parasympathetic hypo- and hyper-activation. This is fight or flight, freeze, arousal, tonic immobility, and collapsed immobility.

4. A bunch of other stuff whose role is harder to understand, like medical history, medication, environment, genes, sleep quality, mental illness symptoms, and a variety of low-level neurobiological dynamics from which priors and attention emerge.

Together, certain sets of priors and avoidance create stable and maladaptive attractor states. The priors involved often erroneously predict threat and powerlessness and therefore activate defense cascade states.

You can permanently destabilize these maladaptive attractor states (and associated defense cascade activation) by updating/reconsolidating the reinforcing priors by activating them and juxtaposing them with strong contradictory evidence that the person may otherwise be avoiding, e.g. the best examples of psychotherapy. This juxtaposition creates prediction error, which updates the priors reinforcing the maladaptive attractor state. Of course this is easier said than done; it’s hard to pay attention to contradictory evidence when you’re in flight or flight or tonic immobility, you feel that feeling emotions is a threat itself, you don't even know what the relevant prior is, etc. I personally think MDMA therapy is particularly helpful here because it seems to facilitate prediction error for most or all maladaptive priors that are activated/triggered during a session and often works during fight or flight or tonic immobility.

Maybe there’s some use in categorizing most mental illness into boxes, but in this model you would still cure it contradictory evidence specific to each case (or possibly through practices that facilitate universally applicable prediction error), so why bother other than for legal reasons.

To be clear, this model doesn’t fully describe disorders involving certain clear biological issues like psychosis (aberrant salience), a swath of neurological disorders, brain damage, etc. This model also doesn't explain anything about how, when, and why a lot of psychiatric drugs work and don't work.

I flesh this out in much more, fully-cited, detail in Chapter 2 of https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394097304_Open_MDMA_An_Evidence-Based_Mixed-Methods_Review_Theoretical_Framework_and_Manual_for_MDMA_Therapy.

Thank you, Awais, for a thorough and thoughtful survey of this fraught topic--one I have been grappling with for four decades! I would like to suggest another way of looking at the concept of "validity" in psychiatry--one that shifts the discussion from etiological considerations to pragmatic, instrumental and ethical issues. I discuss this under the rubric of "instrumental validity" in this article:

https://scispace.com/pdf/toward-a-concept-of-instrumental-validity-implications-for-4j3yc4xt2d.pdf

The core of my thesis is as follows:

"Following the pragmatic tradition of William James and John Dewey, I define “instrumental

validity” as that property of a diagnostic criteria set which bears on how fully it achieves a par-

ticular aim or goal. Now - to hyper-condense along argument - I believe that the fundamental

goal of general medicine and psychiatry is to reduce certain kinds of human suffering and inca-

pacity..."

With respect to general medicine, I think that the issue of "validity" does arise fairly frequently, albeit (usually) without the polemical flourishes that typically accompany discussions in psychiatry. For example, there is intense interest and discussion regarding the validity of the entity commonly called "Long Covid" See:

https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/what-long-covid-can-teach-psychiatry-and-its-critics

There are other debates that border on the "validity" question in general medicine and neurology, such as whether Persistent Idiopathic Facial Pain is a valid diagnosis (this was formerly known as "atypical facial pain")

Best regards,

Ron

Ronald W. Pies MD