RDoC more than a decade later: humbler and wiser?

It has always seemed to me that the popular understanding of the principles and implications of NIMH’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) was shaped by the words of Thomas Insel, former NIMH director, to the detriment of the framework. In the early days of my psychiatric training, the version of RDoC that I encountered was the version put forth by Insel, and as far as I can tell, it still shapes how clinicians and the public understand it.

A good example of what I’m talking about comes from the 2010 paper in American Journal of Psychiatry by Thomas Insel, Bruce Cuthbert, and others. I presume it was primarily written by Insel, because he is the lead author, the language matches what Insel said elsewhere in blogs and interviews, and because articles with Cuthbert as the lead author (e.g. Cuthbert & Insel, 2013) seem to be more careful in what is asserted.

The 2010 article introduced RDoC to many in the psychiatric community, and this is the language they encountered:

“the RDoC framework conceptualizes mental illnesses as brain disorders. In contrast to neurological disorders with identifiable lesions, mental disorders can be addressed as disorders of brain circuits.”

“RDoC are intended to ultimately provide a framework for classification based on empirical data from genetics and neuroscience.”

“The primary focus for RDoC is on neural circuitry, with levels of analysis progressing in one of two directions: upwards from measures of circuitry function to clinically relevant variation, or downwards to the genetic and molecular/cellular factors that ultimately influence such function.” (my emphasis)

To make matters worse, for many clinicians and many outside psychiatry, their first introduction to RDoC was in 2013, a few weeks before the release of the DSM-5, when Insel announced in a post on the NIMH’s Director’s Blog that “NIMH will be re-orienting its research away from DSM categories.” As noted by a 2013 letter in American Psychological Association’s Monitor on Psychology, “The press and bloggers quickly labeled the announcement an “abandonment” of the DSM.”

Much of the initial scientific and philosophical critique of RDoC was directed at the version articulated by Insel, with criticisms often highlighting the implicit neuro-reductionism, the problems with conceptualizing mental illnesses as disorders of brain circuity, assuming that answers will come from genetics and neuroscience, and implying that clinical diagnostic categories could be given up so easily.

It took me years to realize the discrepancy between what Insel had promoted as RDoC and what the framework itself had to offer.

Joshua Gordon in his blog posts as NIMH director has been much clearer about the nature, scope, and limitations of the RDoC project. Writings from Gordon, Cuthbert, Sanislow, and others have clarified that RDoC is not a diagnostic system and is not intended to be; it is not intended for practical clinical use in the near future; it doesn’t define mental disorder; and that it is an experimental framework with uncertain prospects of success.

In this context, a 2022 article Revisiting the seven pillars of RDoC in BMC Medicine by RDoC leadership offers a good reminder of what RDoC is about and where it stands now.

The article notes: “The relationships between RDoC and diagnostic manuals and the role of RDoC in NIMH research funding have both become clearer since RDoC was launched. Specifically, existing diagnostic criteria remain the standard for clinical use, while research that informs clinical decision-making and may inform future changes to diagnostic practice and criteria (including research that adopts RDoC principles) carries on concurrently. NIMH never stopped funding research focused on existing diagnostic categories but encouraged investigators to critically examine their assumptions about diagnosis-based classification and to consider alternative approaches.”

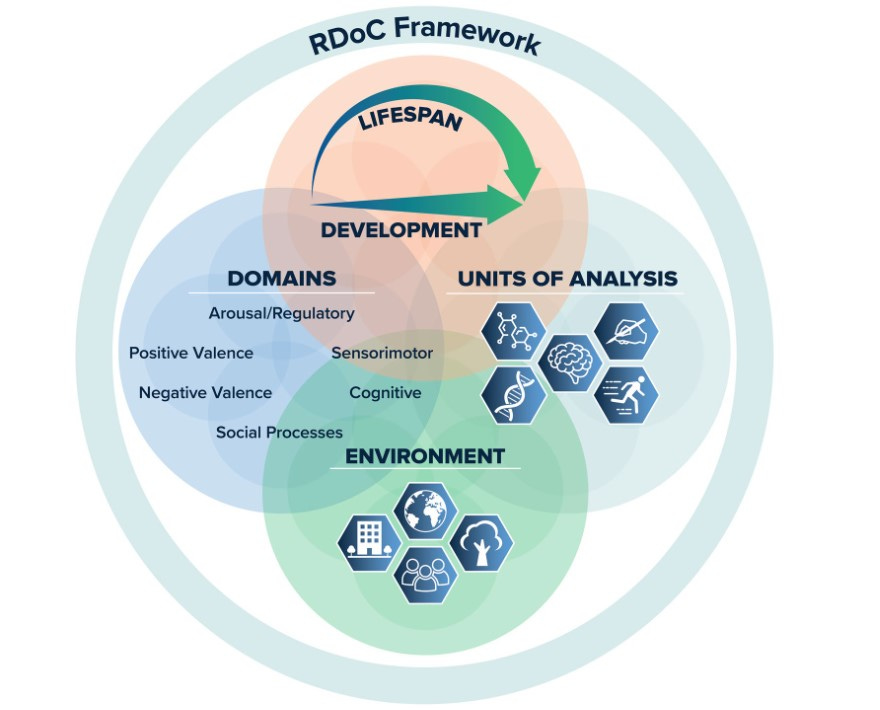

It’s interesting that the article says: “… the term “units of analysis” was deliberately chosen [in the RDoC framework] over “levels of analysis” for referencing measurement classes so as to not inadvertently imply reductionism.” In contrast, the 2010 Insel et al. article used levels of analysis: “The columns of the matrix denote different levels of analysis, from genetic, molecular, and cellular levels, proceeding to the circuit-level (which, as suggested above, is the focal element of the RDoC organization), and on to the level of the individual, family environment, and social context.” (my emphasis)

While the early RDoC writings had emphasized the “domains” and the “units of analysis” as the two core elements of RDoC, the 2022 article places them on equal footing with “development” and “environment.”

Morris et al. state that “the aim is to encourage psychopathology research that frames hypotheses in terms of neurobehavioral constructs rather than groupings based on predetermined diagnostic criteria” and that “RDoC is intended to generate a literature that can (among other goals) inform future versions of diagnostic systems rather than create an alternative clinical manual. RDoC is sometimes described as an alternative to existing diagnostic systems, but such framing erroneously implies a shared scope and purpose.”

“RDoC is intended to generate a literature that can (among other goals) inform future versions of diagnostic systems rather than create an alternative clinical manual. RDoC is sometimes described as an alternative to existing diagnostic systems, but such framing erroneously implies a shared scope and purpose.”

They further clarify: “RDoC domains and constructs, in and of themselves, do not necessarily define valid clinical entities for the purposes of clinician communication, drug development, or regulatory processes but the framework serves as a roadmap via which translational behavioral neuroscience research may converge with diagnostic practice.”

One of the clearest signs of conceptual maturity comes from this paragraph:

“In spite of a decade of changes, it is possible that RDoC has become over-reliant on the matrix. The pace of science has become so fast that it is extremely difficult to maintain the process of evaluating and curating new domains, constructs, and methodologies. Accordingly, the matrix risks ending up in the midst of another prescriptive system that is antithetical to its goal. Although thoughtful effort has been put into the changes, we have simultaneously begun to de-emphasize the specific content and structure of the RDoC matrix. Rather, we encourage investigators to consider the domains, constructs, and elements of the matrix to be exemplars and to focus on the principles of the framework (e.g., brain-behavior constructs, dimensional functions, and integrative analyses) within the context of environmental factors and developmental processes in considering their research plans. This shift in emphasis away from the matrix and toward a more holistic concept is reflected in the recently updated graphic depiction of the framework in Fig. 1.” (my emphasis)

Encouragingly, the terms “brain circuit disorder” or “brain disorder” do not appear even once in the 2022 article, nor does the assertion that the primary focus for RDoC is on neural circuitry.

On the whole, it is welcome to see that RDoC leadership has continued to distance itself from the trappings conferred on RDoC by Insel, and that they are humbler and clearer about RDoC’s relationship to clinical practice, more aware of the prospects of reductionism, and are wisely emphasizing fundamental principles such as dimensionality, integration, and developmental context instead of reifying the RDoC matrix.