Reflections on Canalization and Psychopathology

A new descriptive metaphor for psychological entrenchment in mental illness

In the paper “Canalization and plasticity in psychopathology,” Robin Carhart-Harris, Karl Friston, and colleagues use the construct of “canalization” to describe a new account of a general factor of psychopathology. They suggest that psychopathological phenotypes develop via mechanisms that lead to a narrowing of the “phenotype state-space.”

The paper is not easy to read. The writing is unnecessarily complicated, the use of terminology is often idiosyncratic, there is an excessive devotion of acronyms and neologisms, and the barrage of references, detours, quotes (from authors such as Lao-Tzu, Gabor Maté, and Thich Nhat Hanh!), and explanatory qualifications is simultaneously distracting and amusing. Nonetheless, the paper explores an important and tantalizing idea that deserves our attention and reflection.

The heart of the paper is the notion of “canalization.” The basic idea can be stated quite simply: it refers to how features of the mind, brain, or behavior become less able to change in a non-specific way.

The notion that mental illness generally involves some form of rigidity or inflexibility of thought and behavior is a relatively common one. The idea takes many different shapes and forms. Kristopher Nielsen, for example, describes mental disorders as mind's ‘sticky tendencies’ and Sanneke de Haan uses the flexibility of sense-making in relation to the world as one of the general characteristics of psychopathology: “A second criterion concerns the flexibility of sense-making, in particular the flexibility of someone’s pattern of interacting with the world and others. Does the person get stuck in an inflexible pattern of acting and reacting, even when it does not fit the situation?... Psychiatric disorders often involve a ‘freezing’ of a certain sense-making.” (Enactive Psychiatry; p209-210)

So we may ask the question: what does canalization add to this general recognition?

Carhart-Harris et al. write:

“Our general theory states that: cognitive and behavioral phenotypes that are regarded as psychopathological, are canalized features of mind, brain, or behavior that have come to dominate an individual's psychological state space. We propose that the canalized features develop as responses to adversity, distress, and dysphoria, and endure despite, rather than because of, evidence. We also propose that their depth of expression or entrenchment determines, to a large extent, the severity of the psychopathology, including its degree of treatment-resistance and susceptibility to relapse.”

Waddington introduced “canalization” in biology in 1942 as a way of referring to phenotypic stabilization.

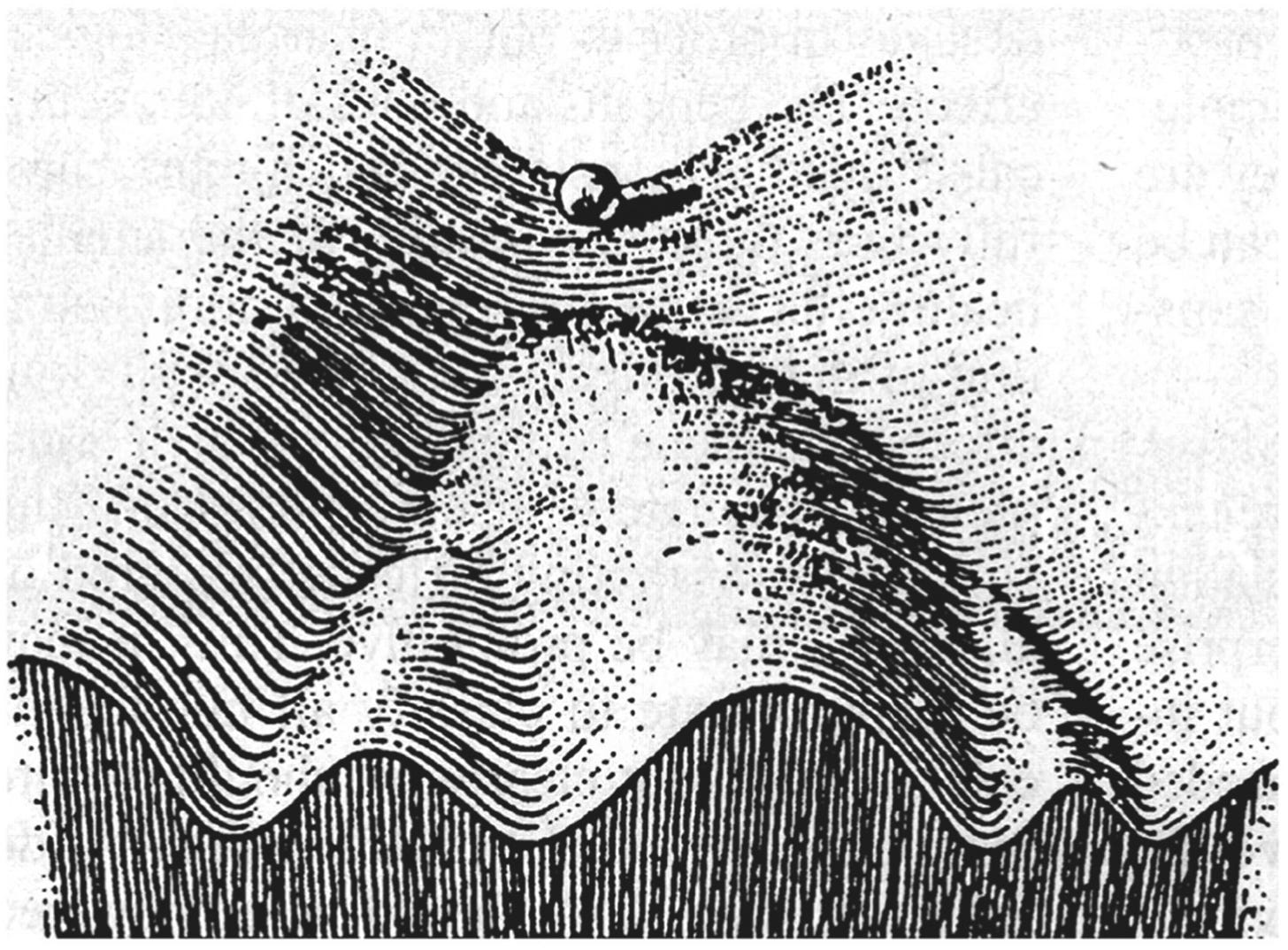

“Waddington invites us to imagine a ball rolling down a gradient featuring various valleys of differing depth. Within this metaphorical image, the steepness and depth of the valley or ‘canal’ walls, is meant to reflect the strength or depth of canalization, encoding phenotypic precision.

Translating this image into a more modern, energy landscape representation, the valleys or canals represent dynamical attractors, whose gravitational pull is also encoded by the steepness of their walls and overall depth. Within a free-energy scheme, the landscape represents a gradient descent, and the steepness and depth of the valleys relates to their precision-weighting, i.e., steep and deep valleys encode precise models. Translating to psychology, we can imagine a valley as representing a cognitive or behavioral phenotype, feature, or ‘style’, and its depth and steepness is intended to encode its strength of expression, robustness, influence, and resilience to influence and change.”

Canalization serves here as a “powerful bridging construct” that connects many different ideas:

Entrenchment of a psychological phenotype

Dynamical attractors in dynamical systems (from Wikipedia: “In the mathematical field of dynamical systems, an attractor is a set of states toward which a system tends to evolve, for a wide variety of starting conditions of the system. System values that get close enough to the attractor values remain close even if slightly disturbed.”)

Minimization of variational “free energy” (i.e., a quantitative, statistical score of surprise or uncertainty)

High precision (or confidence) of prior beliefs in Bayesian terms, such that priors are resistant to updating in the face of new evidence (e.g. in predictive processing models of the Bayesian brain)

Hebbian neuroplasticity (“neurons that fire together, wire together”) – a change in synaptic pattern such that a particular pattern of neuronal firing is now more likely than it was before.

Increased modularity of brain circuit networks

The common feature among all these is that the range of possibilities previously allowed by the system has been narrowed or restricted (“canalized”) in some form or fashion. All of these can be visualized as a Waddington landscape. Being able to visualize and conceptualize something familiar in new ways can be very useful in science, as it allows us to utilize theoretical tools developed in other areas and disciplines in surprisingly productive ways.

The idea that psychopathology involves entrenchment is not by itself that innovative, but once we conceptualize that entrenchment as canalization, we can now link it to evolutionary phenotypic variation, dynamical systems, the free energy principle, Bayesian frameworks, Hebbian neuroplasticity, etc. and apply ideas from these areas to the study of psychopathology.

The idea that psychopathology involves entrenchment is not by itself that innovative, but once we conceptualize that entrenchment as canalization, we can now link it to evolutionary phenotypic variation, dynamical systems, the free energy principle, Bayesian frameworks, Hebbian neuroplasticity, etc. and apply ideas from these areas to the study of psychopathology.

In addition, canalization as a bridging construct provides inspiration for hypotheses about how psychopathological phenotypes relate to changes in synaptic neuroplasticity or brain circuit modularity, etc. Carhart-Harris et al. are interested in experimental validation, discuss various biomarker candidates, and offer predictions. In this regard, it would be important to clarify that it is not canalization itself that can be investigated and tested, but rather a range of different hypotheses that are inspired by the general idea of canalization and that give it a specific shape and form.

The paper, however, goes further than offering an account of canalization.

It offers canalization as an account of the p-factor. The p-factor was described by Caspi et al. in 2014 as a factor that accounts for meaningful variance across major forms of psychopathology, and it is a notion that has been formally incorporated into the HiTOP model.

p-factor is popular among folks who like to theorize about mental disorders as ultimately arising from one etiological factor (e.g. Christopher Palmer proposed that metabolic dysfunction is the p-factor, a proposal I’ve reviewed here). Carhart-Harris et al. are doing something more subtle than proposing a common etiology. They are proposing canalization as a common dimension of processes involved in psychopathology, but it is easy to lapse into thinking of the p-factor as a real, causal, latent variable whose existence can be tagged, e.g., with a biomarker, and in some parts of the paper, there is a tendency to treat the p-factor in exactly this fashion.

A paper posted on psyarxiv just yesterday by Ashley Watts et al. offers a critical evaluation of the p-factor literature:

“The p-factor is relatively novel construct that is thought to explain and maybe even cause variation in all forms of psychopathology. Since its “discovery” in 2012, hundreds of studies have been dedicated to the extraction and validation of statistical instantiations of the p-factor, called general factors of psychopathology. In this Perspective, we outline 5 major challenges in the p-factor literature, namely that it has: (1) mistakenly equated good model fit with validity; (2) sought to corroborate weak p-factor theories through underspecified construct validation efforts; (3) produced poorly replicated general factors of psychopathology; (4) violated assumptions of latent variable models; and (5) reified general factors of psychopathology as latent, causal entities, in turn neglecting alternative models that do not incorporate a p-factor and are entirely incompatible with the notion that a single dimension adequately summarizes variation in all forms of psychopathology. Each of these challenges raise questions about substantive interpretations of the p-factor (i.e., negative emotionality, thought disorder), undermining the field’s confidence that the p-factor is a real, latent entity, or that GFPs are useful summaries of psychopathology variation.”

Considering the baggage that surrounds the p-factor, I suspect that Carhart-Harris et al. will be better off not linking the two, so that canalization doesn’t live and die with the p-factor (Carhart-Harris et al. write in the paper: “Our model rests, to a large extent, on the legitimacy of ‘p’…”). Canalization can very well be an important aspect, dimension, or characterization of psychopathology, but there is no need to wed it to the idea that a single dimension adequately summarizes variation in all forms of psychopathology.

Canalization can very well be an important aspect, dimension, or characterization of psychopathology, but there is no need to wed it to the idea that a single dimension adequately summarizes variation in all forms of psychopathology.

Carhart-Harris et al. take the view that what “classifies a psychological or neurobiological phenotype as pathological, is its degree of entrenchment, influence, and resistance to revision e.g., in response to new contexts or evidence.” They say that canalization in the beginning may be an “adaptive response to adversity, distress or dysphoria” but becomes maladaptive as “too dominating of a person's future cognitive and behavioural state-space” even though it longer offers the benefits it once did in a prior context.

“Is canalization intrinsically ‘bad’, and plasticity, intrinsically ‘good’?

The answer here is, of course, “no”. In the same way that Hebbian plasticity is essential for healthy learning and development, so is canalization and consolidation of “well-trodden paths” – see also (Moran et al., 2014). Thus, we must address why and when canalization can become maladaptive. To provide a meaningful answer to this, information is needed on: 1) the nature of the phenotype that is canalized; 2) the extent to which it is canalized; 3) the context in which processes of canalization first occurred; and 4) whether that current context has changed.”

At another place they refer to the idea of harm:

“Again, the pathological style could be seen as adaptive for the individual – at least in the short-term, yet dissonant with, and potentially threatening to, community norms and values. In other word, the psychopathology may be Bayes-optimal for a person with a particular history; however, their emergent prior beliefs may nevertheless dissonate with new contexts or diverge from community norms and values in a way that is harmful for the individual or the community (Wakefield, 1992) – yet they ‘cannot help it’.”

This is all well and good, but this is by no means an improvement over current common-sense, value-laden, context-sensitive judgments of psychopathology in terms of adaptiveness and harm that clinicians currently rely on (see this and this); it is simply a restatement of these judgments.

One reason Carhart-Harris et al. are interested in canalization is because where canalization provides a transdiagnostic feature of psychopathology, psychedelic interventions offer a transdiagnostic cure. Carhart-Harris and Friston had previously hypothesized (in the REBUS model) that psychedelics decrease the “precision-weighting” of the brain’s predictive models. The notion of canalization now allows them to restate this in terms of psychedelics counteracting the process of canalization and making phenotypes more flexible again, allowing them to escape the maladaptive state in which they were stuck.

“The REBUS model relates well to the canalization model of psychopathology (or ‘CANAL’, for short), presented here. The former is specific to the action of psychedelics, whereas the latter has evolved from this specific application to appeal beyond it, i.e., to the notion of a single dimension of ‘psychopathology’ (Caspi et al., 2014) and how this might be understood and treated. The two models are consistent, in the sense that REBUS offers a mechanistic explanation for how psychedelic therapy can ‘treat’ canalized phenotypes, i.e., the model states that via a drug-induced entropic action, psychedelics plasticize reinforced patterns of cognition and behavior.

The combination of REBUS and CANAL can help to explain the putative transdiagnostic efficacy of psychedelic therapy (Kocarova et al., 2021), and it also inspires speculations about psychiatric symptoms that may be especially amenable to psychedelic therapy; i.e., those that most compellingly fit the model of pathology by canalization.”

Carhart-Harris et al. conclude their proposal as follows:

“The present work has introduced a new and intentionally parsimonious model of mental illness, based on the phenomenon of canalization. The model proposes that entrenched canalization, acquired in response to adversity, distress or dysphoria, is a principal component of psychopathology. The model takes inspiration from the (re)emergence of a putative transdiagnostic treatment for psychopathology; namely, psychedelic therapy. We propose that psychedelics promote an early form of plasticity (TEMP), which, when combined with gently guiding psychological support, can serve to counter entrenched canalization.”

Canalization is a descriptive metaphor; it is a way to visualize the entrenchment of psychopathology in terms of a landscape of variation and flexibility. It allows us to see commonalities between the entrenchment of psychopathology and attractors in dynamical systems, free energy minimization, Bayesian inference, Hebbian neuroplasticity, and brain modularity. For canalization to offer an explanatory account of psychopathology, however, further models are needed that hypothesize specific, testable relationships between psychopathological phenotypes and brain processes and the influence of therapeutic interventions. The clinical use of psychedelics in the treatment of psychiatric disorders offers a productive opportunity for the development and investigation of such explanatory models.

I wish I'd found your excellent and, importantly, clear summary before I got bogged down and eventually turned off by the knotty writing and surfeit of acronyms and buzz-words in this paper. I would agree that canalization works as a really good metaphor for describing some forms of psychopathology but my concern is that the authors and others will see it as much more than a metaphor and before you know it we will have a new catch-all explanation for all mental disorders...

I admitingly don't read full papers as much as I could, but (as someone already interested in most the work of Carhart and Friston) I read this one all the way through when it came out. It still echoes in my thoughts now. This is a great summary. I appreciate the p factor push back - I think I needed that!