The Human Challenge of Schizophrenia

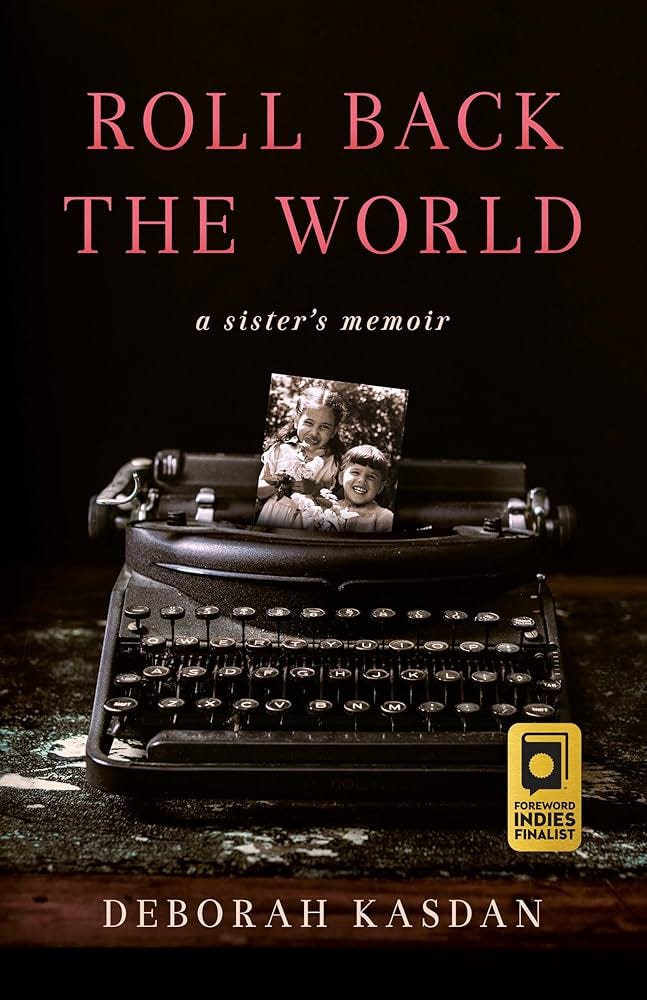

Book Review: Roll Back the World by Deborah Kasdan

Deborah Kasdan’s Roll Back the World: A Sister’s Memoir (2023) is an honest and vulnerable account of her sister Rachel’s life with schizophrenia and the challenges this presented for the family. Kasdan grapples with grief, love, frustration, and self-reflection in equal measure as she recounts a life lived under the shadow of severe and persistent mental illness, with rare moments of reprieve, stumbling through a healthcare system poorly equipped to provide the necessary care.

Rachel Goodman received a diagnosis of schizophrenia in the mid-1960s when she was 23 years old, after several years of prodromal erratic behavior and functional decline. It seemed like “an alien force took possession” of her sister. Rachel’s life became a demoralizing cycle of hospitalizations and treatments, such that it was often unclear what was doing more harm, the illness or the treatment. Her family struggled to arrange the necessary support for her in the community, and Rachel resisted and resented the family’s efforts to keep her safe. Kasdan’s own guilt resonates throughout the memoir and is a reflection of the challenges faced by families navigating mental illness.

Her early treatment with antipsychotics in the St. Louis state hospital system improved her psychotic symptoms, but it also subdued her personality and left her with serious side effects, such as tardive dyskinesia and diabetes, while doing frustratingly little to improve her daily functioning. The system prioritized control over understanding and overlooked her intelligence and creativity in a manner that left her alienated.

The clinical reality of serious and persistent mental illness cannot be ignored or wished away. Roll Back the World is an unflinching record of the impact of schizophrenia, an observation of the failures of the mental healthcare system, and the tremendous difficulty of finding a life worth living under the circumstances.

A letter Deborah wrote in 1966 details her first encounter with a medicated Rachel in the hospital. She notes with alarm that Rachel’s self-destructive rebelliousness had been suppressed, but “nothing has replaced it,” leaving an empty and docile shell of a person.

“October 27, 1966. She doesn’t write [poetry] now; she doesn’t fight the world anymore. Instead… she is making a purse in occupational therapy, which she says is something nice to do. The Rachel I knew before would never say such a thing… I don’t understand what they’ve done to her, Barry. I realize that the almost grotesque kind of rebellion which formed the basis of her behavior and thought before could only lead to self-destruction. Now there’s none of the old thing… but nothing has replaced it. She is tractable and docile, expresses only the blandest of feeling… My parents want her to stay hospitalized—they say that since she hasn’t really faced and coped with those old emotions, they will lead to the old behavior if she is on her own. And if they allow her to be released, they have no way of keeping tabs on her or controlling her since she’s over twenty-one. I know there’s a lot of truth in that reasoning, yet the alternative of keeping her hospitalized seems so unreasonable and even inhuman.

I trust my parents about this, but sometimes I don’t. I can’t stand it. I find it unbearable to think that her life, potentially such a rich one, is being dried up and shriveled away there so that she is happy making purses in occupational therapy. I’ve been so caught up in my own problems and worries that I’ve hardly thought of Rachel’s dilemma. And now, for the first time—perhaps since the summer of ‘65 when they committed her—I’m crying for her. I have this nagging guilty feeling that I should try to persuade my parents to do something else with Rachel, but I have no idea of what to suggest.” (p 140-141)

Kasdan’s reaction on watching One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest is one of annoyance:

“I wished that people who cheered the high jinks of a countercultural figure whose rebellion symbolized resistance to a repressive, conformist culture could understand that my mentally ill sister was no metaphor. I wished they knew that her life in and out of hospitals didn’t represent any higher truth.” (p 158)

Eventually, Rachel was placed in a community program by the state hospital. Her father wrote in a letter to the Missouri commissioner in charge of the state’s department of mental health:

“The hospital personnel anticipated that she would adjust in the community, but Rachel has in fact deteriorated into a hopeless, defenseless, disoriented person incapable of the minimum amount of self-care.” (p 163).

The hospital refused to readmit her after she left the boarding house to which they had discharged her. She went to Columbia, Missouri, where she ended up in jail for several weeks for shoplifting. She remained adrift and dislocated in the community, and one night she “burst into the house imploring us to let her have a place to spend the night.”

“My wife and I find the present situation unbearable. At this moment we don’t know where Rachel is nor can we be sure that if she returns, things will be any better.” (p 164)

In 1977, he filed a federal lawsuit against St. Louis State Hospital, arguing that Rachel had a right to protection and treatment as long as her medical condition required it.

The contemporary impulse behind the “bring back the asylum” argument relies on the same sense of frustration that drove Rachel’s father to try to force the state hospital to keep her hospitalized indefinitely. When the choice is between coercion and abandonment, it is unsurprising that many choose incarceration for their loved ones, but our collective inability to think beyond this dichotomy is an ethical, social, and clinical failure.

The contemporary impulse behind the “bring back the asylum” argument relies on the same sense of frustration that drove Rachel’s father to try to force the state hospital to keep her hospitalized indefinitely.

Rachel herself was unhappy about these legal efforts and wrote to her parents in a letter in 1979 while admitted to St Louis, “I suppose you are doing well in your court trials… Perhaps you will win, but some people are against you. I do not know if you are doing any good except for a few.” (emphasis in original, p 166)

Her brother Michael felt that the parents were trying to “keep her locked up forever.” He was concerned by this and fought for a different arrangement. Michael eventually convinced the family to allow him to take Rachel to Seattle with him. He made a heroic effort and cared for Rachel in a truly dedicated manner, but the arrangement soon came apart. Michael and Rachel began to clash; Rachel resisted her brother’s efforts to constrain her impulses; the struggles became physical; and she voluntarily admitted herself to Harborview Hospital.

A dejected and demoralized Michael wrote in a letter to his parents:

“Rachel is indeed very disturbed. And if she can make any improvement in the future at all, it will be on her own terms. My involvement was fraught with dangers, mistakes, and illusions. Washington State [hospital system] is not too bad for Rachel at this juncture.” (p 191)

Deborah writes, “My brother had been so brave and hopeful. Now even he had to give up his dream of healing Rachel.” (p 191)

This is the juncture in the book where the gravity of Rachel’s illness hits readers with full force. This is not a simplistic story where doctors are the villains and the patient finds healing once removed from their claws by a loving family. Chronic schizophrenia is a disruptive force that leaves families desperate and helpless.

“Rachel lived with Michael for only three months before leaving to check into Harborview Hospital for two weeks. She was soon released to a group home. She had never adapted to group living situations in St. Louis and she didn’t out West either. She was picked up by the police, committed by the court, and sent to Western State Hospital in Fort Steilacoom, a repurposed military facility south of Tacoma, Washington.

After another round of discharge and arrest, she decided to take off. She crossed the border to Oregon, where she was picked up for shoplifting and arson. She was committed by court order to Dammasch State Hospital, near Portland.

Thus began her Oregon years, where she remained for the rest of her life. Between 1980 and 1992 Rachel would be released, readmitted, and transferred back and forth among three different Oregon hospitals: Dammasch, Oregon State Hospital in Salem, and Eastern Oregon Psychiatric Center in Pendleton. She stayed in hospitals, shelters, halfway houses, and boarding houses. Sometimes she camped outside in the woods.” (p 192)

Deborah wonders:

“We didn’t make a new plan; we just let things happen. Michael stayed in Seattle, Mom and Dad in St. Louis, Julie in New York, and I in Connecticut. We let Rachel stay out West because why? Because the hospitals there seemed better than St. Louis? So Mom and Dad could finally enjoy their life? Because Rachel would do better amidst woods and mountains than urban squalor? She would be better off, wouldn’t she? And that’s what she wanted, wasn’t it? I managed to convince myself she did.

Years later, I learned differently. In the basement of my long-widowed mother’s St. Louis home, I found the letters Rachel wrote to my parents during that first year out West. I looked at them and put them away. Took them out and read them again: twenty-two letters in which she pleaded with them to bring her home. She wrote them to Mom and Dad both, but many to Dad alone. My hands trembled when I saw notes marking the date of receipt in Dad’s handwriting. Why was he saving all her letters if he didn’t plan to take her back? I was overcome with the despair he must have felt. Despair and determination.” (p 196)

While hospitalized at Dammasch, Rachel was being considered for a supervised housing and work program, and she was assigned janitorial responsibilities on a trial basis. Steve, a social worker, was helping her with this process. One day he went to check up on her and found a poem she had written and was stunned. He shared it with a colleague who was similarly impressed. This cemented Steve’s determination to get her into the rehabilitation program.

“When Rachel moved into the first apartment Laurel Hill obtained for her, Steve visited her every day to help her with the transition. He made sure she had help with the skills she needed to survive in the real world. Shopping. Money. Medications. Help with her diabetes. These were the skills that would keep her away from prostitution, shoplifting, and camping out with winos. Steve was determined to anticipate her needs before a crisis could develop. His approach worked. After a few months he could see she would never have to go back to the locked wards of Dammasch. He continued to encourage her to work on her poetry, which he eventually put into [a] booklet…” (p 243)

“Nobody could give Rachel back her intact mind, but Steve helped restore her dignity. The fact of her freedom, that gift of compassion from Steve, consoled me. Without it, I doubt I could ever have forgiven myself for abandoning her.” (p 244)

Life was not hunky-dory, however, and it is important to note how impaired she still was. Rachel had difficulty tolerating house rules and housemates, and eventually the agency found her a small home in the woods, “in an unincorporated, unzoned community in a no-man zone between Eugene and Springfield,” an area that was “a refuge for trailers, meth users, the homeless, and people on the margins.” It was here that Rachel could finally be herself.

When her mother visited her for the first time, she was initially taken aback.

“The kitchen was littered with remains of cat food tins, unwashed dishes, pamphlets, opened bottles of milk, and cracker crumbs. It was a shocking sight… I saw my mother’s anger and bewilderment when she looked at Rachel, who commanded her surroundings with a sense of regal decrepitude. Why couldn’t Mom just be glad that Rachel had a place of her own?” (p 253-254)

Caring for her still wasn’t easy. Agency staff would try to bring her medications and insulin regularly, but she would often be away from home. Sometimes she’d refuse to go to appointments. She’d use the money from her disability check for tobacco. The agency would send cleaning crews, but she would deny them permission to enter.

“When your sister walks around with a face scarred from years of skin infections that she didn’t want to cleanse, toothless because psychotropic meds have dried the teeth out of her mouth and she won’t wear her dentures, squinting because she won’t use her glasses, and coughing because nicotine is the only thing that can counteract the fog of medication in her brain, you tell yourself that you have to accept what can’t be changed.” (p 269)

“Thanks to Laurel Hill, Rachel lived the rest of her life, four more years, in this house in the woods. Mom didn’t visit again, but she seemed to accept Rachel’s situation: that Rachel had people to bring her medications and make sure she had food. She was safe and protected, just as our mother had always wanted. I had my own reasons to be happy for Rachel. She had a home, her very own, where she was free to come and go as she pleased. Exactly what I had most wanted for her. And when people asked how Rachel was doing, I had an answer I wasn’t ashamed to give.” (p 258)

A bittersweet conclusion, an unlikely measure of dignity and autonomy achieved under impossible circumstances. It is a tragedy that so many individuals with serious mental illness live their lives without even achieving that.

This is not the best we can do. Trieste’s mental health care system and Open Dialogue in Western Lapland are demonstrations of what is achievable if the human dimension of psychosis is taken seriously.

Serious and persistent mental illness is a scientific challenge of daunting complexity—our neuroscientific understanding is rudimentary and our medical treatments are painfully imperfect—but it is also a humanistic challenge. Individuals with schizophrenia need pride, meaning, self-esteem, and agency to flourish as much as anyone else, perhaps even more so. How our collective lives can be organized to make these possibilities accessible to individuals like Rachel is a social challenge rivaling the scientific one, and it is a task we have long neglected.

See also:

Such an important account. I must get a copy. Thank you

Thank you for sharing these excerpts and to the author for their determination in telling and revealing a painful truth.