The Rumpelstiltskin Effect: Meet the Name for the Relief a Diagnosis Brings

Alan Levinovitz (Professor of Philosophy and Religion at James Madison University) and I have a new article out today in BJPsych Bulletin, “The Rumpelstiltskin Effect: Therapeutic Repercussions of Clinical Diagnosis,” in which we give the healing power of diagnosis a befitting name. The article is open access, and we encourage you all to read it. The following is an abbreviated version of the original.

Clinicians across medical disciplines are intimately familiar with an unusual feature of descriptive diagnoses. The diagnostic terms, despite their non-etiological nature, seem to offer an explanatory lens to many patients, at times with profound effects.

In a New York Times story about ADHD diagnoses in older adults, a woman diagnosed at age 53 described her reaction as follows: “I cried with joy,” she said. “I knew that I wasn’t crazy. I knew that I wasn’t broken. I wasn’t a failure. I wasn’t lazy like I had been told for most of my life. I wasn’t stupid.”

Clinicians in a variety of disciplines and settings see this dynamic play out in diverse diagnoses: tension headache, tinnitus, chronic fatigue syndrome, restless leg syndrome, insomnia disorder, irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, chronic idiopathic urticaria, and autism spectrum, to name a few.

Their experiences highlight a striking, neglected, and unchristened medical phenomenon:

The therapeutic effect of a clinical diagnosis, independent of any other intervention, where clinical diagnosis refers to situating the person's experiences into a clinical category by a clinician or the patient.

We call this the Rumpelstiltskin Effect.

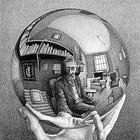

In the classic Grimms’ folktale, “Rumpelstiltskin,” a young woman promises her first-born child to a little man in exchange for the ability to spin straw into gold. When he comes to collect, she begs for mercy, and he offers her a way out. She must guess his name.

Now a queen, the woman runs through every name in the German language, as well as every colloquial nickname she can think of. None work. Finally, her servant discovers the little man’s highly esoteric name—Rumpelstiltskin—and she is released from her obligation.

Crucially, the source of the queen’s severe distress does not have a familiar name. Nor can she substitute a layperson’s description like “funny little man.” Esoteric knowledge of an official name is required to gain control over what ails her. As soon as she knows the name, the problem takes care of itself.

This type of folktale (Aarne-Thompson Tale Type 500) appears in numerous cultures. The details vary, but the theme is identical. Discover the esoteric name, control, and destroy the source of suffering. Traditional exorcism works according to a similar principle. Ordinary terms exist for the afflictions attributed to demons: sloth, mendacity, gluttony, and so on. However, when normal efforts to overcome sloth are inadequate, an exorcist is brought in. Discovering the demon’s name is crucial to controlling it—not merely sloth, but Belphegor, the demon of sloth—which is why demonological treatises and exorcists spend so much time on names, from ancient China to modern England. Other examples abound, from cultural practices of keeping true names secret to contemporary literature such as Ursula Le Guin’s classic Earthsea book series, in which mages can only control what they correctly name.

This principle is also at work in modern medicine. If a clinical diagnosis can have a therapeutic effect, then, at least in some instances, diagnoses are medical interventions in themselves, and ought to be treated and researched as such. Likewise, self-diagnosis can be understood as an attempt to secure the therapeutic effect of a medical intervention to which patients do not have official access.

Though the phenomenon has not been extensively studied under this name, research already points to its reality. Systematic reviews of diagnostic labeling (O'Connor et al, 2018; Sims et al, 2021) show that a new name for an old struggle often brings validation, relief, and empowerment. It provides a common language for talking to doctors, family, and peers. It can enable connection to supportive communities and advocacy movements. Rumpelstiltskin effect also seems a plausible cousin to the placebo effect, where expectations alone produce measurable changes in symptoms.

Possible mechanisms

1) Clinical lens and hermeneutical breakthrough

Fundamentally, a clinical diagnosis invites patients to see their experiences through a medical lens. The medical interpretive framework recognizes suffering in ways that everyday language often cannot because the latter tends to characterize problems as personal inadequacies. Clinical language is also more standardized than everyday language, which offers at least the appearance of a cohesive explanatory framework for a person’s impairment.

The philosopher Miranda Fricker uses the example of postpartum depression to illustrate how the act of naming a phenomenon can serve as a transformative moment of understanding. In her 2007 book Epistemic Injustice, she quotes a woman describing her first encounter with postpartum depression as a medical diagnosis:

“In my group people started talking about postpartum depression. In that one forty-five-minute period I realized that what I’d been blaming myself for, and what my husband had blamed me for, wasn’t my personal deficiency. It was a combination of physiological things and a real societal thing, isolation. That realization was one of those moments that makes you a feminist forever.” (p 149)

The lack of a recognized concept for postpartum depression created a “hermeneutical darkness,” a gap in collective understanding that deprived individuals of the ability to fully comprehend their experiences.

In addition to a medical label, a diagnosis also functions as a social tool for making previously unarticulated suffering comprehensible. Feeling understood, by oneself and others, is a psychological good that could contribute to the Rumpelstiltskin effect. The official name serves as a bridge between individual experiences and generalized patterns.

2) Learned associations, the power of rituals, and the sick role

The act of diagnosis is in most cases a prelude to medical care and treatment. Another mechanism at play in the Rumpelstiltskin effect may be an acquired association between the naming of a condition in a medical context, the promise of relief, and access to the “sick role.” When a patient receives a diagnosis, it offers hope and reassurance. The association can continue to play out even in situations where a diagnosis is made but treatment is not sought or none is available.

This process is further amplified by the power of culturally sanctioned rituals. Diagnostic terms are ritualized constructs imbued with institutional authority. When a condition is officially named by a specialist, it acts as a conditioned stimulus, evoking an expectation of care and recovery that has deep roots in human societies. The anticipatory relief would be particularly effective within cultural contexts that position medical diagnoses as authoritative and transformative.

3) Relief from cognitive ambiguity

Receiving a diagnosis resolves the cognitive ambiguity that attends unexplained suffering. Patients with undiagnosed problems frequently struggle with confusion and have difficulty communicating their experiences to others and even to themselves. A descriptive diagnosis provides a prototypical explanation that alleviates these difficulties. Although it does not offer an etiological answer, descriptive diagnosis functions as a framework that organizes disparate symptoms into a legible and standardized pattern: a recognized problem shared by people across the world with core symptoms that have been described in textbooks and studied by experts. A diagnosis alleviates uncertainty by introducing a categorical label around which a narrative can be built. A diagnosis gives patients the tools to construct a story that explains their suffering and renders it comprehensible.

Interestingly, we see this potential mechanism in the origins of the Rumpelstiltskin story. The etymology of the little man’s strange name is typically traced to a German household imp, “little rattle stilt,” who was blamed for unexplained noises and mysterious movement of objects. This esoteric name is actually an explanation of the otherwise inexplicable.

Diagnosis and iatrogenic harm

Medical diagnoses also have potential downsides. A diagnosis can also bring fear, stigma, and unintended self-limitation. It can alter how people see themselves and how others see them, sometimes in alienating ways. In psychiatry especially, labels can carry cultural baggage, lead to discrimination, or encourage looping effects in which the diagnosis shapes behavior and identity in self-reinforcing cycles. Some people reject diagnostic framing entirely, preferring to see their experiences as spiritual, creative, or otherwise outside the language of disorder. For them, the official name can feel intrusive, even harmful. And when a diagnosis is misunderstood as a fixed defect, it can undermine agency, turning into a self-fulfilling prophecy. The initial therapeutic bump can also fade if the promised benefits, such as effective treatment and a supportive community, do not materialize.

Clinical implications and research directions

If the Rumpelstiltskin effect is as real and common as we suspect, it raises practical questions. Clinicians should be aware that part of a patient’s improvement may stem from the naming itself, not just the treatment. When a patient seeks a specific diagnosis, it can be useful to explore what they expect that diagnosis to give them and to consider whether those needs can be met alongside or apart from the label. We call for a structured research program to explore and quantify this effect and understand its relationship to related phenomena such as the placebo effect. Such work could refine clinical practice and help patients access the benefits of naming without falling into its traps.

The Rumpelstiltskin effect reminds us that the symbolic, the cultural, and the narrative are woven into the fabric of medicine. Naming can be a part of healing. It is time we study this effect with the attention it deserves.

Read the full article in BJPsych Bulletin: “The Rumpelstiltskin Effect: Therapeutic Repercussions of Clinical Diagnosis.

Psychiatry at the Margins is a reader-supported publication. Subscribe here.

See also:

This was such a thoughtful, nuanced, and deeply humanistic piece. Thank you both for the clarity and gentleness with which you approached it.

One thought it stirred for me is about the “sick role” and its unspoken contract. Sociologists outline the benefits of the sick role (support, care, legitimacy), but in practice there are also many obligations woven in. We expect the sick person to minimize their suffering, to comply with treatment (even if it's painful or results in a loss of dignity or autonomy), to “fight,” to contribute when able, to not overburden others, etc. In that light, I sometimes wonder if the relief of receiving a diagnosis isn’t just about gaining benefits, but about being granted permission to set down some of those obligations -- obligations which can, of course, be a heavy and sometimes unbearable burden.

Expanding our view of the sick role as including both benefits and obligations seems to explain why a diagnosis of cancer rarely feels like relief, while in other contexts a label can feel like an immense unburdening. It's the "relief" from those obligations that feels therapeutic. Diagnosis soothes -- even when it does not better explain, change, or treat the underlying condition, or erase any suffering -- because it loosens the burden of expectation.

Of course, humans are hypersensitive to situations where we worry others are accepting our gifts of time, care, and attention without fulfilling our expectations of what they will do in return. So we cannot help but attune to how well this balance between the benefits and obligations of the sick role is negotiated. Certainly, the old paradigm of "diagnosis as stigma or burden", where the sick person suffered all the obligations of the sick role but without the benefits like care, support, and empathy, was certainly a worse way of managing this trade-off. Stigma shows us the cruelty of obligations without benefits, while relief shows us the kindness of being allowed, if only for a moment, to set some obligations down.

And yet, setting down obligations is a tricky dance. Each burden we put down may become one that others must carry. Who decides whose load is heaviest? Perhaps part of our work is simply to recognize that this balance between benefits and obligations is always being negotiated, and to approach that negotiation with humility and care.

Absolutely fascinating and rings true for many people I've observed. And I think it's often NOT about prelude to treatment or accomodations. I've encountered many people who seemed to have gained a lot of relief and peace from the diagnostic label *even if the label was nothing but the concise explanation for their cluster of symptoms*. To use a simplistic example, it seems to go like this: "I'm not shit at maths, I have dyscalculia" --- even though "dyscalculia" is literally a word used to mean being bad at maths. I'm not oversensitive, I have RSD, even tho RSD is *literally* a name give to oversensitivity to rejection. Etc etc etc. I don't understand this at all, on a personal level, but I suspect it might be related to the fact that many people see *mental dysfunction without a medical used label* as a MORAL FAILURE. Which is very sad in itself.