Too Mad to be True III: The Paradoxes of Madness

Conference Review by Joshua Richardson

Joshua David Richardson is a Registered Psychotherapist and philosophy graduate living and working in Ontario, Canada.

Here he shares his review of the 2024 conference “Too Mad to Be True III.” He previously reviewed “Too Mad to be True II” for Psychiatry at the Margins.

The Too Mad to Be True conference is a paradox. By this I mean that it is a contradiction. On the one hand, it is a conference: a deliberately organized and purposely executed congregation upon a central theme. But on the other hand, it is a happening, in the sense descended from the 1960s counterculture and avant-garde art scene: an event birthed from spontaneity and creative unpredictability. On one hand, its speakers are people who experience psychosis first-hand, but on the other they are clinicians who care for those experiencing mental illness. This apparently paradoxical conference-happening takes place in a former asylum (Museum Guislain, Ghent, Belgium), but it is also linked to a working psychiatric hospital. The 2024 edition of the conference is hence appropriately titled The Paradoxes of Madness. The conference is a hybrid affair, which one can attend in person or online. This year I attended online. You can read my review of the 2023 edition, which I attended in person here. With over seventy presenters sharing their thoughts on the paradoxes of madness and mental illness in different keynote addresses and parallel sessions over two full days, it means there is little time to reflect on the abundance of learning while taking in all it has to offer. And so, my aim here is to give some time and space to reflect on the paradoxes of Too Mad to be True.

The tone was set by conference co-organizers Jasper Feyaerts and Wouter Kusters, and the Museum Dr. Guislain’s artistic director Bart Marius. Feyaerts began the conference by reflecting on a quote from a letter written by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein to Maurice O’Connor Drury, a pupil who became a psychiatrist:

“If I became mad, the thing I would fear the most would be your common-sense attitude. That you would take it all as a matter of course that I should be suffering delusions. You should never cease to be amazed at the symptoms mental patients show and treat every patient as an individual enigma.” — Wittgenstein to Maurice O’Connor Drury

This quote helps illustrate a key paradox in some common-sense attitudes toward mental illness: if clinicians assume that someone is delusional and ‘take it all as a matter of course,’ they are apt to miss meaningful aspects of a patient’s lifeworld. One must be open to the meaningfulness in the apparent meaninglessness of mental illness. Marius then invited attendees to take in the museum’s artistic and historical exhibits, and ponder the paradoxes of being free to wander the halls of a former asylum. Within its 19th century architecture, the Museum Dr. Guislain exhibits an array of artifacts from and about the history of mental health systems, as well as historic and contemporary art and installations from and about people with lived experience of madness. Kusters’ address reflected on the paradoxes of the lifeworld and system in madness and mental health treatment. Inside the walls of the former asylum, the lifeworlds of attendees are embedded in the system of the conference and host institution. Philosophical reflection, through deconstructive analysis, can help elucidate certain aporias, or irreducible paradoxes, with the aim of liberating our lifeworlds from systems’ reduction of lived experience to binaries of mad / sane, normal / abnormal, function / dysfunction, so on and so forth. Feyaerts and Kusters perform an admirable balancing act as conference co-organizers. They carefully curate a conference that balances presentations from psychiatric survivors and experts-by-experience alongside professionals and mental health clinicians, who are sometimes one and the same person or persons. It is this precarious balancing act that gives Too Mad to be True much of its dynamism, without which it may simply fall into the heap of countless other conferences and happenings.

The sheer abundance of presenters makes it impossible for one to take in everything at Too Mad to be True. I will share my reflections on a small selection of three presentations: one from a person with lived experience of madness, the next from a mental health researcher, and a third from a collaborative group of researchers and experts by experience. The complete program and videos of the presentations are available from the Too Mad to be True website.

One’s thoughts are perhaps inevitably drawn into a dizzying vortex while reflecting on an event based around the themes of madness and paradox. Thankfully the presenters skillfully pilot their audience through this heady experience, best embodied perhaps by the first keynote speaker, artist and educator Lorna Collins. At the age of 18, Collins suffered an acquired brain injury that resulted in a coma, complete amnesia, and a variety of psychiatric illnesses. Her work is accomplished through the paradox of making sense of the nonsensical: through her artistic practice, Collins communicates her experience of madness to others, educating and working to develop an understanding within the broader community aimed at breaking down stigma. Collins effectively translates between the clinical language of psychiatric illness and that of lived experience, a skill integral to her work as a Peer Support Worker with the NHS in the UK and as Patient Representative with the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Her presentation was a critical lesson on how communication can be embodied in an artful bridging of the clinic and the community.

Ananda Krishnan, a research scholar at the Indian Institute of Technology in Hyderabad, India, provided deep insight into the cultural context of mental health care in India with his presentation on Paradoxical Attitudes Toward Mental Health Problems in India. Krishan’s work argues that many Indians hold paradoxical views regarding mental illness, which in turn can complicate their access and relationship to mental health services. Through historical and cultural analysis, he shows how madness is both lauded and derided in traditional beliefs about the mind, the nature of madness, and its treatment. Krishnan puts forth that the impact for women in India is of particular significance. Based upon the belief that women experiencing mental crises are possessed by spirits, families and individuals seek healing at temples, through various rituals and traditional remedies, rather than accessing Westernized mental health services through hospitals and community clinics. Krishnan makes an excellent case for culturally competent mental health systems which integrate the understanding of traditional beliefs in order to communicate more effectively with patients and communities, thereby increasing their accessibility. Krishnan’s position is a helpful reminder of how far we have to go in the way of critically assessing our own background beliefs regarding madness, let alone those of the people who are systematically excluded from mental health services.

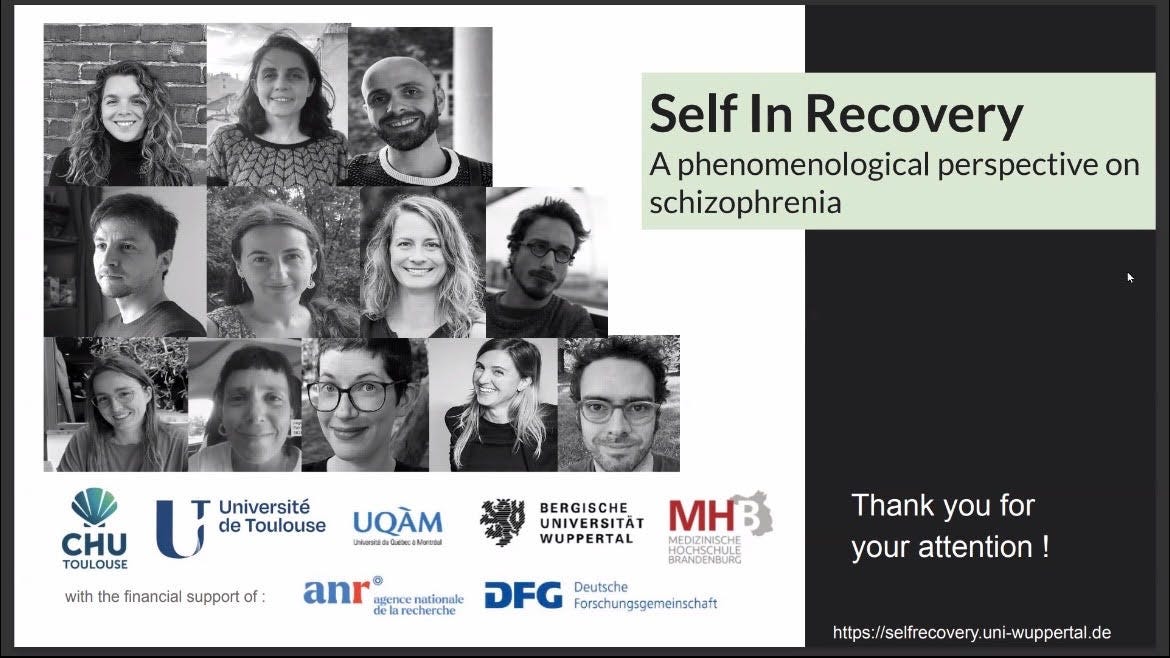

An international group from France and Germany is also challenging paradoxical views of madness. The Self in Recovery: A phenomenological perspective on schizophrenia project brings together experts by experience and researchers in order to investigate recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Their project aims at a person-centered account of recovery based upon descriptions of lived experience, using the conception of schizophrenia as a disorder of ipseity, or selfhood. Hearing people speak about their lived experiences of schizophrenia and how they recovered some greater sense of self over time, one is struck by the painful contradictions and paradoxes of losing one’s sense of self. The Self in Recovery project is perhaps the apogee of what Too Mad to be True represents: the critical and systematic cooperation between people with lived experience of madness, along with those interested in working together to deepen our collective knowledge and understanding of the experience of madness.

The third edition of Too Mad to be True shows that there is indeed much relevance in communicating between the public and professionals at the intersections of madness and mental illness. Too Mad to be True stands as a model for how to integrate discussions of lived experience alongside mental health systems in a self-reflective, critical manner. It is not all harmonious; dissonance abides. But, by engaging with the paradoxes of madness, its contradictions, contrariness, and incoherence, Too Mad to be True advances the conversation in a direction that one might paradoxically call reasonable.

I read your introduction as saying the speakers had both lived experiences and were clinicians... Only to discover you were referring to a peer worker, who is not classed as a clinician here in Australia, has no AHPRA (health professional) registration... provides non-clinical services... Yet you call them a clinician??? Unfortunately this sets me up to be disappointed in the peer worker, for lacking clinical competency, rather than just appreciating the input of a peer worker, who makes their living from their lived experience. I didn't read anything that specified any of the contributors were truly clinicians - psychiatrists etc, registered health professionals at least - and I would have been fascinated if this conference genuinely was groundbreaking in its foregrounding of their experiences. They do exist, I can think of several practicing psychiatrists with lived experience of serious mental illness.

I wish I had gone to this conference, it sounds fascinating - even us vulnerable people can be exposed to risky ideas by the way! I take a very conventional view to mental illness and spend a lot of time wishing i could really believe in my diagnosis of schizophrenia for which i have been compulsorily treated for the last 14 years - but i do like to challenge and be challenged about my very conventional assumptions.