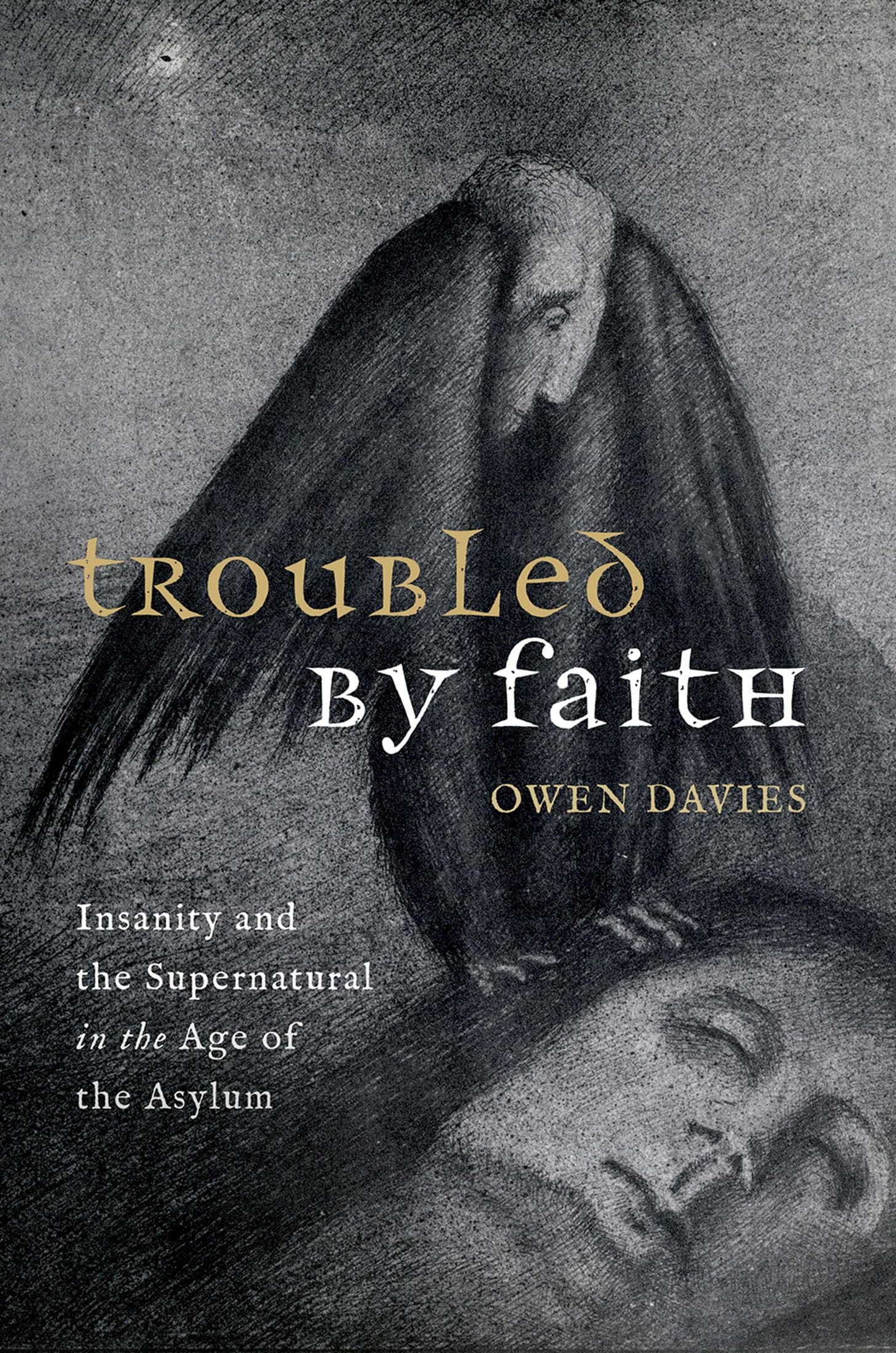

Troubled by Faith: Insanity and the Supernatural in the Age of the Asylum

Book Review by Richard Saville-Smith

Richard Saville-Smith, PhD is the author of Acute Religious Experiences: Madness, Psychosis and Religious Studies (2023, Bloomsbury), which tackles the question of how to speak about experiences of the extraordinary/anomalous/extreme. He has a PhD in religious studies from the School of Divinity at the University of Edinburgh, UK, and he is an independent scholar who lives on the Isle of Skye at the edge of the world. Saville-Smith’s career trajectory has been punctuated by madness, and he seeks to persuade philosophers and scientists to engage more effectively with religious studies in a shared exploration of the role of madness throughout the human story.

Acute Religious Experiences: Madness, Psychosis and Religious Studies is now available in paperback (20% discount code GLRBD8, if purchased through Bloomsbury)

Here Saville-Smith reviews the book Troubled by Faith: Insanity and the Supernatural in the Age of the Asylum by Owen Davies (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Troubled by Faith is a social history of ideas about madness and the supernatural, filtered through the prisms of the histories of psychiatry and primary documentation from asylums. Part one, A World of Insanity, explores the dance between an ascendant modernist psychiatry, the legal system and mainstream Western culture. Part two, Inner Lives, features an exploration of the archives of (primarily) five UK asylums which emerged in the 19th century to accommodate those for whom society was too much, or who were too much for society. Each of these two parts has its own introduction, to highlight the structural distinction, but this is most certainly not two separate books. Instead, it is an ingenious recognition of the value of two distinct but complementary strategies which, as a historian, Davies deploys.

This split-screen approach allows Davies to set out a critical history of the institutional development of psychiatry as it challenged superstition and the supernatural. And in the second part, Davies’ rich archival sources reveal the contemporary face of madness in the 19th century as it was inscribed in the contemporary records. Davies is perfectly transparent that the archive documents are mediated by officialdom, so no claim is made that they directly reflect the voices of the patients themselves, even the letters and direct quotes which survive in the medical notes are not preserved by the agency of patients. As there is every reason to suppose the selection Davies makes includes the more interesting examples, caution is required. But, once these points are accommodated, the archival contribution unlocks a treasure of contemporary accounts which supplement and complement the first contextualizing part of the book disclosing the figures and tropes of madness in the real time 19th century asylum.

With this structure in place Owen Davies, Professor of Social History at the University of Hertfordshire, argues that the mad are profoundly shaped by their cultural worlds. The asylum, as an institution (figuratively and actually) outside of society, includes a population which reflect the very society from which they have been excluded. The accounts from the asylum become the grounds to explore the anxieties and concerns of mainstream society but amplified. This is a novel approach which flips lazy assumptions about the meaningless of madness whilst making a significant contribution to thinking about the world of the mainstream normals through the elasticated eyes of the excluded.

The role of ghosts, witches, angels, devils, fairies, divine communication, and the haunting of modern technology sits uncomfortably with a psychiatric discipline predicated on rationality… Davies is beginning to tell an untold story of how mad people made mad sense of their mad 19th century world.

Davies approach is driven by his focus on the supernatural. The significance of this focus is hard to underestimate. The role of ghosts, witches, angels, devils, fairies, divine communication, and the haunting of modern technology sits uncomfortably with a psychiatric discipline predicated on rationality. If the ghosts, witches, angels, etc. are a priori excluded by a psychiatric opposition to the supernatural, then the color, power and detail of such content is crushed under therapeutic typologies and the diagnoses of psychiatric unbelief. Psychiatrists may select case studies with supernatural content to illustrate their theories, but its abolition is the measure of clinical success. The idea of actually writing about psychiatric subjects, without dismissing or disparaging the words they use to articulate their worldviews, requires that ghosts, witches, angels, imps, devils and fairies, divine communication and the haunting of modern technology are given a degree of respect that even Foucault stumbled over in his History of Madness: there are no fairies in Foucault! Davies is beginning to tell an untold story of how mad people made mad sense of their mad 19th century world. By delving into the data of the supernatural and insisting on taking its mad manifestation seriously as an organic—if aberrant—reality, Troubled by Faith makes a welcome contribution to the historiography of the 19th century social history which should not be limited to the history of psychiatry.

I found it slightly disconcerting that the book begins with a long chapter on the witch trials as these fall well outside Davies’ 19th century time period. But the chapter begins to make sense with the realization that witches are not the actual subject of interest. In Davies’ hands, the witch trials become his first contribution for critically exploring the emerging discipline of psychiatry and its partiality for retrospective diagnoses. Esquirol, Charcot, Janet, Freud and Zilboorg are all shown in their intent to prove the past could be understood scientifically. Davies identifies their desire to find simple overarching explanations for witches and their legal persecution. His treatment of witchcraft in this opening gambit allows him to douse the simplistic science of the psychiatrist with his own retrospective 21st century approach, suggesting the need for a more holistic approach incorporating the ‘interlinked legal, scientific, theological, political, cultural and social developments of the time’.

The second chapter ‘Pathologizing the Supernatural Present’ finds us firmly in the 19th century in conversation about the role of daemoniacs, religious mania, revivals, the role of the churches and the emergence of spiritualism. Telling the stories of the outbursts of Raphania or Methodism broadens into a recognition that religious ecstasy, or its pathologized form of religious monomania (or theomania), bubbled in a European and North American cauldron throughout the 19th century. Davies sets up the French psychiatrist Esquirol’s view that demonic possession has significantly diminished, and was to be found only in the uneducated; along with his other claim that the capacity of religious fanaticism to cause insanity has lost its power due to the loss of influence of religion. These twin claims provide Davies with all the provocation he needs to marshal the evidence on page after page that Esquirol was wrong.

In chapter three, ‘Madness in popular medicine’ Davies presents a number of concise thematic explorations on subjects such as the role of fear, the skies, and fits. My favorite was on the moon. There is something about the power of the moon which is reflected in the tides and the watery composition of not just the brain but the human person. Davies finds the connection between moon/lunar/lunacy with Galen in the second century and bounces it forward into his own time period. There, in the epistemological struggle between science and folklore, attempts to use asylums as petri dishes of lunar excitation are largely abandoned for the more ideological dismissal of folklore in a scientific age. There is nothing tidy about this struggle with The Association of Medical Officers of Asylums and Hospitals for the Insane declaring lunatic an obsolete term in 1855, just 35 years prior to the UK Parliament ensuring its continuation by passing the Lunacy Act in 1890.

Part one is brought to a conclusion with a chapter titled ‘The Mad, the Bad and the Supernatural in Court’ telling the story of muddle and confusion as the psychiatric profession sought to establish its expertise within the court system. This was resisted by some judges and confused even more jurors. The result, for the purposes of this book, are some great stories, but also a refusal of the legal system to accept the psychiatric attempt to locate supernatural beliefs within the category of the pathological. A Davies puts it, ‘The supernatural and superstitious could be found reasonable without being rational, and belief in them were culturally relative rather than medically or historically determined. Whether devils, witches, and spirits were delusions… became largely irrelevant in legal terms.” (p 172)

By drawing on the records of archives found in asylums as the role of Part 2, Davies has considerable freedom to organize his data. He chooses to address religious content, witches and fairies and, finally, the emergence of new technologies. The temptation to look for a linear development should be resisted as the religious and fairy tropes are both ancient. So in the limited space I have I draw attention to Davies treatment of imps and technological development. Imps because ‘patients suffering from delusions of diabolic persecution quite often talked about such imps around them’ (p 201). Whether there is a direct relationship between imps and the machine elves of contemporary 5-MeO-DMT reports is not a matter of sanity so much as an experiential question. The link is found in a consideration of plasticity and the way tropes develop like an infection rather than an orderly school lesson. This is exactly the point Davies finds in a consideration of the way technological developments are incorporated into the vocabulary of madness. Davies opens this section by gently mocking a scholarly book from 1897 suggesting a timeline of 20 years for the incorporation of new technologies into the delusional content of the mad. Davies tartly observes that it was often a matter of months not decades between the advent of new technologies and their appearance in case-notes. This incorporation of the novel into the vocabularies of the mad is a matter of fascination which allows the tropes of the supernatural world to be understood in terms of a cultural utility which has no fixed or finished from.

Davies tartly observes that it was often a matter of months not decades between the advent of new technologies and their appearance in case-notes. This incorporation of the novel into the vocabularies of the mad is a matter of fascination which allows the tropes of the supernatural world to be understood in terms of a cultural utility which has no fixed or finished from.

This is a fascinating book, heavy on detail—which is a good thing—even if sometimes there’s the sense of one thing after another in a list of the extraordinary. Davies has identified, sourced, organized and presented his accumulated data in a way which is reassuringly rich, like a thick ragu with a reliable consistency. I’m slightly less persuaded by the title, Troubled by Faith, as the book is not really about faith, which is not a synonym for the supernatural, so much as it is about trouble, trouble in the everyday cultural epistemologies of the excesses of madness. I was intrigued to observe how Davies navigated the changing language in which the discussion proceeds. Throughout he uses the word psychiatry and psychiatrist for convenience, whilst acknowledging this is sometimes anachronistic. He seems much less sure footed in the language with which to describe the mad. From my own mad studies perspective, the language of ‘mad’ and ‘madness’ has value. Like ‘psychiatry’, ‘mad’ can be anachronistic but it can usefully invoke a contradistinction with insanity. If insanity describes madness which has been pathologized by psychiatric judgement, then the ‘mad’, who are not insane, refers to a wider liminal and unknowable population with extreme but not-necessarily pathological states existing outside of the institutions of the state. This might, for example, include those religious whose trouble with faith is excessive but who do not fit the social criteria for incarceration.

Noticeably absent from the mix Davies presents is the propensity of psychiatrists to engage as activists against Christianity. The process of retrospective diagnoses, which concerns Davies in the context of witchcraft, is also to be found in the psychiatric propensity to retrospectively diagnosis religious ‘greats’ as mentally disordered. Davies nods to this with the examples of Ann Lee, the founder of the Shakers, and the Wesleyan Methodists, but there is a larger canvas where the epistemological conflict between psychiatry and religion plays out as a visceral conflict. The attack of Jesus’s sanity came to an international crescendo, in Davies’ period, with publications by the psychiatrists George de Loosten, Emil Rasmussen, William Hirsch and the four volume La Folie de Jésus (The Madness of Jesus) by Charles Binet-Sanglé. Whereas the retrospective diagnosis of witches was driven by explanatory intent, the motive of these protagonists was not a concern for Jesus’ mental health. If Jesus could be shown to be a madman, Christianity must surely collapse. That it didn’t provides a commentary on the relative lack of power of the insurgent psychiatrists and the deeply established structures of the church(es). Psychiatry may have dominated the world of mental disorder, but its power was both narrow and finite, and this accords with the story Davies tells throughout his book. But there are additional implications:

If both witchcraft and extreme religious experiences can be accommodated within the same psychiatric discourse as subjects in which psychiatrists identified pathology at play, the distinction between witchcraft and such religious experiences may be more flimsy than is normally considered. This suggestion finds support in Tamar Herzig’s paper ‘Witches, Saints, and Heretics, Heinrich Kramer’s Ties with Italian Women Mystics’ (2006). Kramer is the Dominican monk who wrote the Malleus Maleficarum, Hammer of Witches (1487), so it is some surprise to find Kramer involved in the support and wellbeing of female Spanish Mystics. Herzig’s theoretical argument is ‘the very qualities that render women more susceptible to the devil’s machinations also turn them into the privileged conduits for divine revelations that confirm the tenets of Christianity’ (Herzig 2006:52). Herzig is no apologist for Kramer, as her wider discussion of misogyny makes clear, but she is suggesting a chamelionesque quality of acute experiences, which reflects Davies’ ideas of plasticity.

This point can be taken even further by reference to William James the American Psychologist. Davies cites James as saying ‘History shows that mediumship is identical with demon-possession. No one regards it as insanity’ (Davies, p 48). This stands as a challenging statement which could have been further explored. But it can also be set beside James’ argument, in The Varieties of Religious Experience, that religious mysticism and insanity are counterparts as the two halves of mysticism. (James [1902] 1985: 426). James does not specify how the categorical divide between religious mysticism and insanity is traversed, but it is certainly plausible to suggest such distinctions are cultural and contextual. It is relatively straightforward to be critical of psychiatrists retrospectively rethinking both witches and the religious greats. But it is far more perplexing to recognize that these tropes owe so much to their psycho-social context. Both Herzig and James point to, at least, the possibility of a plasticity in which personal intentionality and social context shape the way such roles are established and developed. The ecstatic raptures, stigmatization, ascetic fasts, and eucharistic devotion of late 15th century women mystics are no less challenging than the engagement of witches in the development or acceptance of their own powers or, for some, the aberrant and obsessive behaviors found in the asylums of the 19th century. Davies’ observation about how the content, the tropes and the metaphors of madness could quickly adapt to technological developments confirms the plasticity of madness; and its ability to work with whatever cultural drivers seem to be the most germane to the mad world as seen through mad eyes.

Davies ends his story at the start of the 20th century on the grounds that access to asylum records is limited for a hundred years and the idea of the Asylum ended. My understanding is that there are asylum records available up until 1960 and the emptying of the asylums with the introduction of psychopharmacology would require a different sampling strategy anyway. So, there is most certainly a case for a part II of Troubled by Faith to underscore the continuing role of the supernatural in everyday 20th and 21st century madness.

See also:

Bibliography

Foucault, M. and J. Khalfa ([1961] 2006), History of Madness, New York: Routledge

Herzig, T. (2006), ‘Witches, Saints, and Heretics: Heinrich Kramer’s ties with Italian women mystics’, Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 1 (1): 24–55.

James, W. ([1902] 1985), The Varieties of Religious Experience, London: Penguin Books.

A very interesting summary and review thank you. Just a small point that I hadn't really thought about the distinction between "mad" and "insane" before and I found this interesting