Understanding Detransition(s) in Transgender Healthcare

The diversity of detransition experiences in the DARE study

Kinnon Ross MacKinnon, MSW, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Social Work at York University, Canada. For over a decade, Kinnon’s scholarship has focused on transgender medicine, examining how gender minority people access and experience hormonal and surgical treatments. Kinnon co-writes The One Percent newsletter, and his personal website is available here. He is currently principal investigator of the DARE study, which is supported by a multi-disciplinary team of LGBTQ+ healthcare researchers and is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Around 2018-2020 reports of detransitioning and gender transition regret started to come to light, especially with regard to testimony provided as part of a judicial review of the UK’s Gender Identity Development Service at the Tavistock (Bell v. Tavistock). Through the 2000s-2010s, there were few high-quality research studies on detransition ever conducted. So the phenomenon—as a possible medical outcome—was largely discussed rhetorically to argue for or against gender-affirming care for minors, but without much data to back up the polarized discourse.

The Detransition Analysis, Representation, and Exploration (DARE) study is a community-engaged research project designed to empirically explore detransition, gender identity fluidity, and decisional regret. A long-awaited article from this study was just published earlier this week.

Appearing in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, “A Latent Class Analysis of Interrupted Gender Transitions and Detransitions in the USA and Canada” examines multi-dimensional and contextual factors that can prompt stopping/reversing an initial gender transition. This process is often referred to as “detransitioning.”

The DARE study findings illustrate the complexity and multi-dimensionality within detransitioning, and it provides much-needed data-driven insights into this emerging patient population.

The results also challenge the often simplified, narrow narratives about detransition that can drive culture-war debates over transgender healthcare; detransition is either the canary in the coal mine of gender-affirming healthcare, or it’s only ever caused by social difficulties and external pressures that transgender people face in society (Hildebrand-Chupp, 2020).

Background to the study of detransition

Detransition is a heterogenous concept. It can refer to a process of stopping, shifting, or reversing an initial gender transition (Ashley et al., 2024). For some, it might involve a change in gendered self-concept or identity after starting an initial gender transition. Shifting from a transgender or nonbinary identity to a sexual minority identity (e.g. lesbian, gay, bisexual or queer), or evolution from a binary transgender identity (boy/man; girl/woman) to nonbinary (genderqueer; gender-fluid) are common identity change pathways found in detransition research. Medical detransition often involves discontinuing hormonal treatments for gender dysphoria, and in more rare circumstances, pursuing a reversal/reconstructive surgery following gender-related surgery. The prevalence of discontinuing hormonal treatments among TGD youth and young adults ranges from 2-30% (Expósito-Campos et al., 2023), with this wide range being largely explained by study design, methodology, and clinic-specific or geographical considerations.

Some transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) young people experience shifts in gender identity or sexual orientation identity as a normative aspect of their psychosocial development (deMayo et al., 2025). Identity fluidity and shifts in self-concept are also among the predominant reasons people may detransition or discontinue a medical transition pathway. Other major factors can include health concerns or complications with treatment, lack of support or discrimination coming from the external environment, interpersonal stressors, feeling that treatments did not resolve gender dysphoria, mental health-related concerns such as mental health not improving after gender-related treatments, and difficulty with accessing healthcare such as financial barriers to hormones/surgeries (MacKinnon et al., 2025).

Detransition has also been commonly conflated with the experience of regretting prior hormonal or surgical treatments for gender dysphoria. In reality, detransition and decisional regret can overlap, but the extent to which they co-occur varies. Some studies have shown a minority who detransition express transition regret (MacKinnon et al., 2022), whereas other studies indicate that detransition and regret closely converge (Kettula et al., 2025). More complex emotions about the initial transition process are also typically present such as a mix of grief, ambivalence, and positive emotions (Pullen Sansfaçon et al., 2023). Some TGD people report temporary, interrupted gender transitions due to social pressure or minority stressors like employment discrimination, and they may later re-engage with a gender transition process (sometimes called “retransitioning”) (Walls et al., 2024).

Recent research with adolescents and young adults

In recent years there has been a paradigm-shifting emergence of LGBTQ+ young people who report extensive gender fluidity and identity exploration that was not observed in older clinical research with transgender/transsexual adults. Today, longitudinal studies with TGD youth and young adults estimate that between 19% to more than 50% report shifts in gender identity over time (de Rooy et al., 2023; deMayo et al., 2025; Katz-Wise et al., 2023; Ocasio et al., 2024). This fluidity appears to be more common amongst gender-diverse young people assigned female at birth (AFAB) (MacKinnon et al., 2025). Gender identity/expression shifts are not necessarily signs of psychopathology, but may be a fundamental aspect of adolescent identity development, gender expression, and meaning-making in the world. For this reason, though, moving forward with gender-related medical interventions in children and youth is considered a higher-stakes clinical decision when compared to adults (Brierley et al., 2024).

Discontinuing hormonal treatments does not necessarily imply regret or detransition. In some cases, a TGD person has met their treatment goals and they report satisfaction with care. Yet, since 2021 there has also been an increase in research on detransition showing some people indeed feel dissatisfied with treatments received for gender dysphoria (Vandenbussche, 2022).

While such experiences appear to compose a minority experience among those who have accessed transition-related medical care, there is still a need for greater understanding and clinical knowledge to enhance informed decision-making when starting an initial medical transition. As well, there is a need for clinical guidance to support individuals who are pursuing a detransition process.

But on the academic side of things, making decisions about how to study these experiences in a highly politicized, polarized landscape (and among increasing backlashes to transgender inclusion in society) is not an easy task.

A muddled academic terrain

Long before the word “detransition” began to enter the popular lexicon by the mid-2010s, clinicians were aware of the reality that gender transitions could be complex and non-linear.

Historically, the term “regret” in transgender medicine was used to describe unexpected, non-linear gender outcomes. In trans medicine, regret was never exclusively operationalized to measure negative subjective feelings about treatments expressed by a patient. It could refer to outward changes in gender expression, applying to reverse legal documentation after an initial gender transition, or patients expressing regret with the original gender-related diagnosis and dissatisfaction with treatments.

So the term “regret” in transgender healthcare has a fascinating, yet byzantine, academic legacy. It’s been operationalized in a vast number of ways, leading to today’s inheritance of conceptual confusion and difficulty with making comparisons to past research (MacKinnon et al., 2023).

More recently, some clinician-scientists have advised using more precise terminology. Rather than use the concept of “detransition,” it’s been suggested to study separately: 1. discontinuation of hormonal treatments; 2. identity fluidity; and 3. regret (Turban et al., 2022).

Yet, these phenomena can overlap, but the extent to which they converge (and in which contexts) is unknown.

For this reason, one of the goals of the present analysis was to generate greater conceptual and dimensional clarity to enhance academic, clinical, and LGBTQ+ community knowledge. While it appears to be a relatively rare outcome, in absolute numbers it appears to be more commonly reported. Detransition/regret can also have a major impact on individual patients’ lives and on the field of transgender medicine overall.

How was the study designed?

The DARE study had two primary aims:

to characterize pathways to detransition and build empirically-driven knowledge about it;

to generate practical knowledge to improve healthcare experiences and supports, especially within LGBTQ+ communities

To achieve these aims, we used a community-informed, multi-pronged recruitment approach to obtain a large, demographically diverse sample from across the U.S. and Canada. It was a mixed-methods design, starting with a cross-sectional survey and followed by qualitative 1-1 interviews with select survey participants. The survey was available from December 2023 to April 2024. The survey was pilot tested for language/concept accuracy, programming bugs, and logical flow with a range of transgender, nonbinary, and detransitioned people, including gender clinicians. For more information about the survey design and sampling strategy, please see MacKinnon et al., 2024.

Briefly, to be eligible to take the survey, participants provided written informed consent, including consenting to the collection of their IP address data to confirm geographic inclusion eligibility. Participants also confirmed they met all of the following requirements:

Age 16 or older;

Have ever stopped, shifted, or reversed an initial gender transition (or desire to detransition but feel unable to take any steps);

Currently live in the USA or Canada;

Able to complete a survey in English, French, or Spanish

The survey was quite long, taking around 35-60 minutes to complete it, and the questions were comprehensive. We collected demographic data and self-reports on current and lifetime gender identities, diagnosed mental health conditions, physical health, and transition/detransition histories. The survey also included standardized questionnaires such as the Decision Regret Scale, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) questionnaire, and the Recalled Childhood Gender Identity scale, among other validated instruments.

Two important points regarding study interpretation:

1. Data collection timing: Survey data were collected between December 2023 and April 2024. Data collection therefore ended before many age restrictions on gender-affirming healthcare were rolled out in Republican-controlled U.S. states. It is possible that our results on pathways to detransition could look differently if we repeated the study again in 2025-2026 because the broader social context can impact pathways to detransition.

2. Clinical implications: The study does not conclude with recommending state-imposed age restrictions on gender-affirming healthcare, nor does it support clinical efforts to change LGBTQ+ people’s sexual orientations, gender identities, or gender expressions (also referred to as “sexual orientation/gender identity conversion efforts” or “conversion therapy”).

Results: More than one way to detransition

We surveyed 957 people who had undergone a social and/or medical transition at some point in their lives, and who reported later experiences of detransition. Participants ranged in age from 16 to 74. On average, participants were in their mid-twenties at the time they took the survey. Likely due to the two countries’ population size differences, nearly three-quarters lived in the U.S. and the rest were Canadian residents. 79% of participants were AFAB, and most were LGBTQ+ (with bisexual and lesbian sexual orientation identities being the most prominent). Roughly two-thirds had accessed at least one transition-related medical intervention such as hormonal treatments or surgery. To better understand unique pathways to detransition and related care needs, we conducted a latent class analysis of the survey data.

We recently posted a “quick n’ dirty” demystification of latent class analysis (LCA) and the DARE study on The One Percent Substack. You may want to check that out before reading further if you’d like more granular knowledge of the methodology and how we identified different detransition subtypes. Briefly, the LCA was conducted to understand profiles, or subtypes of detransition, looking at who clusters with whom and why.

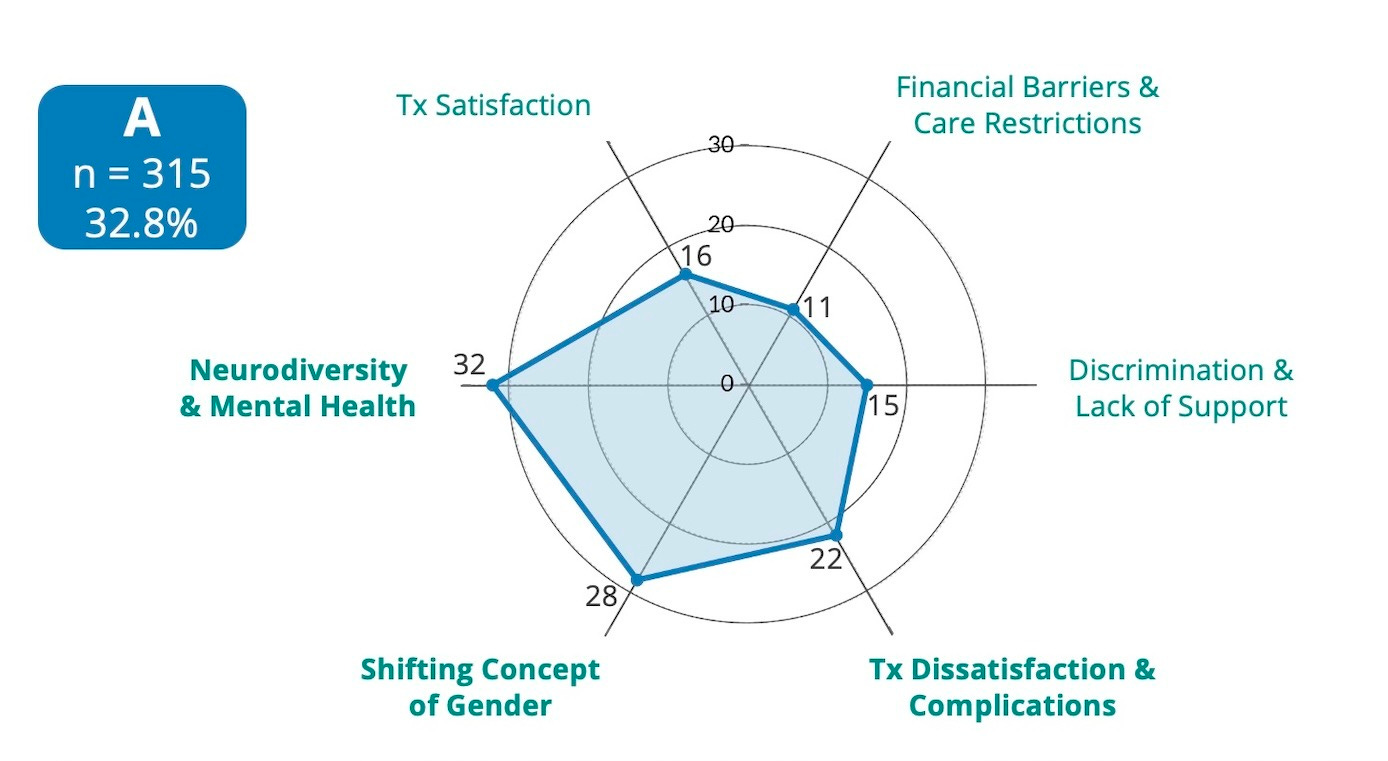

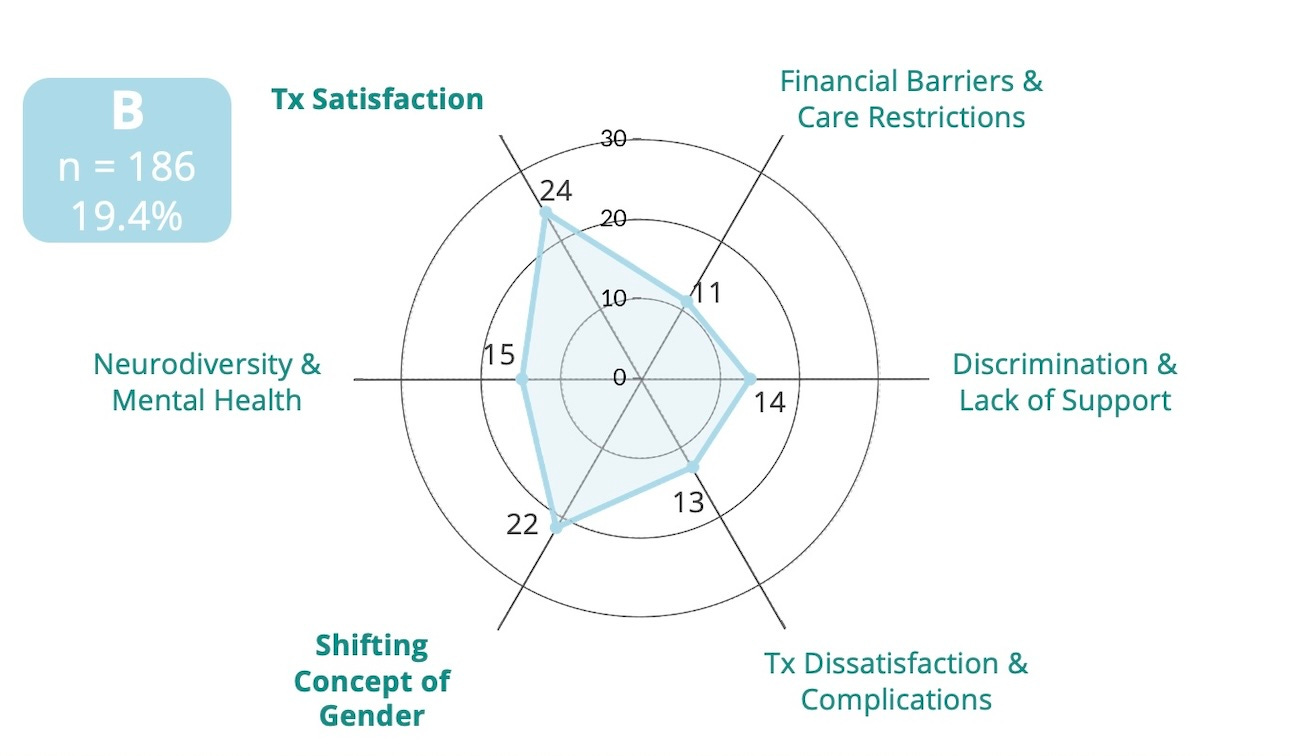

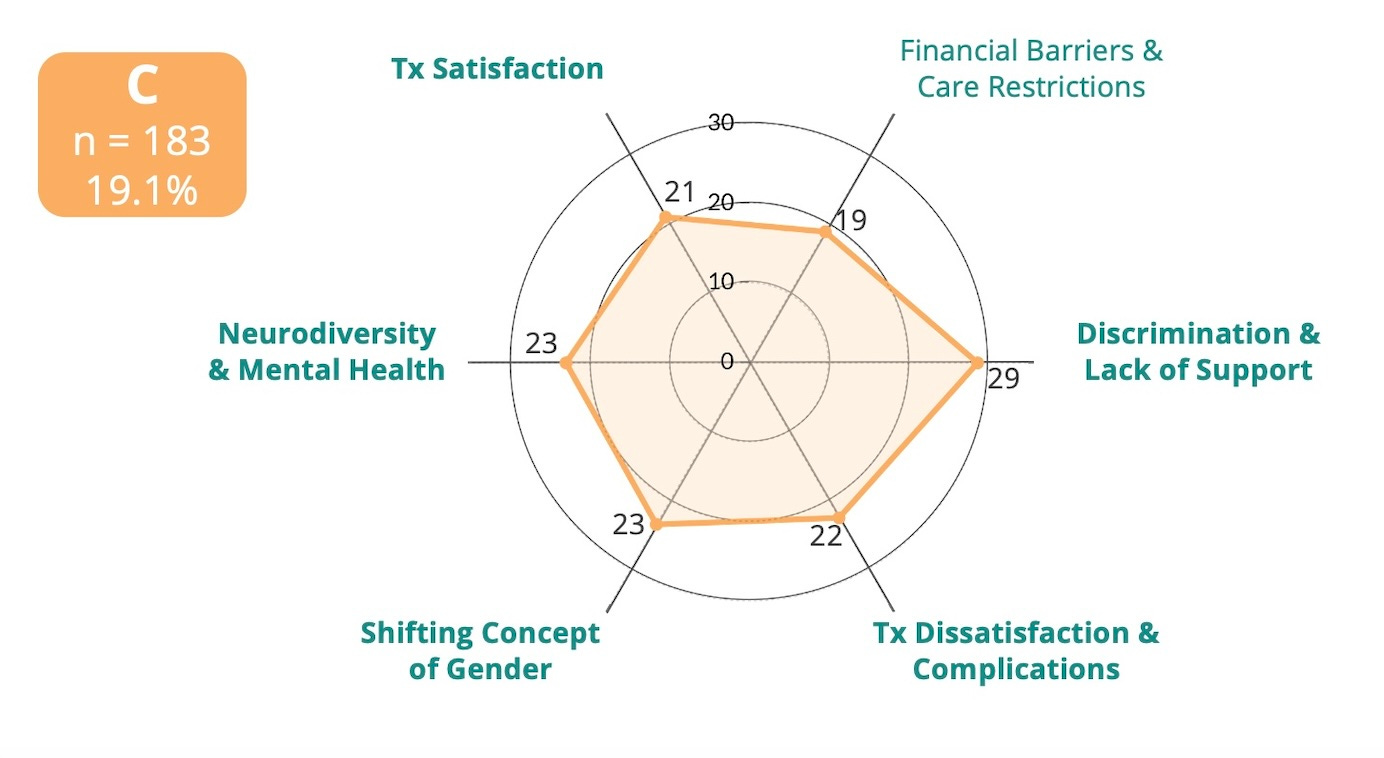

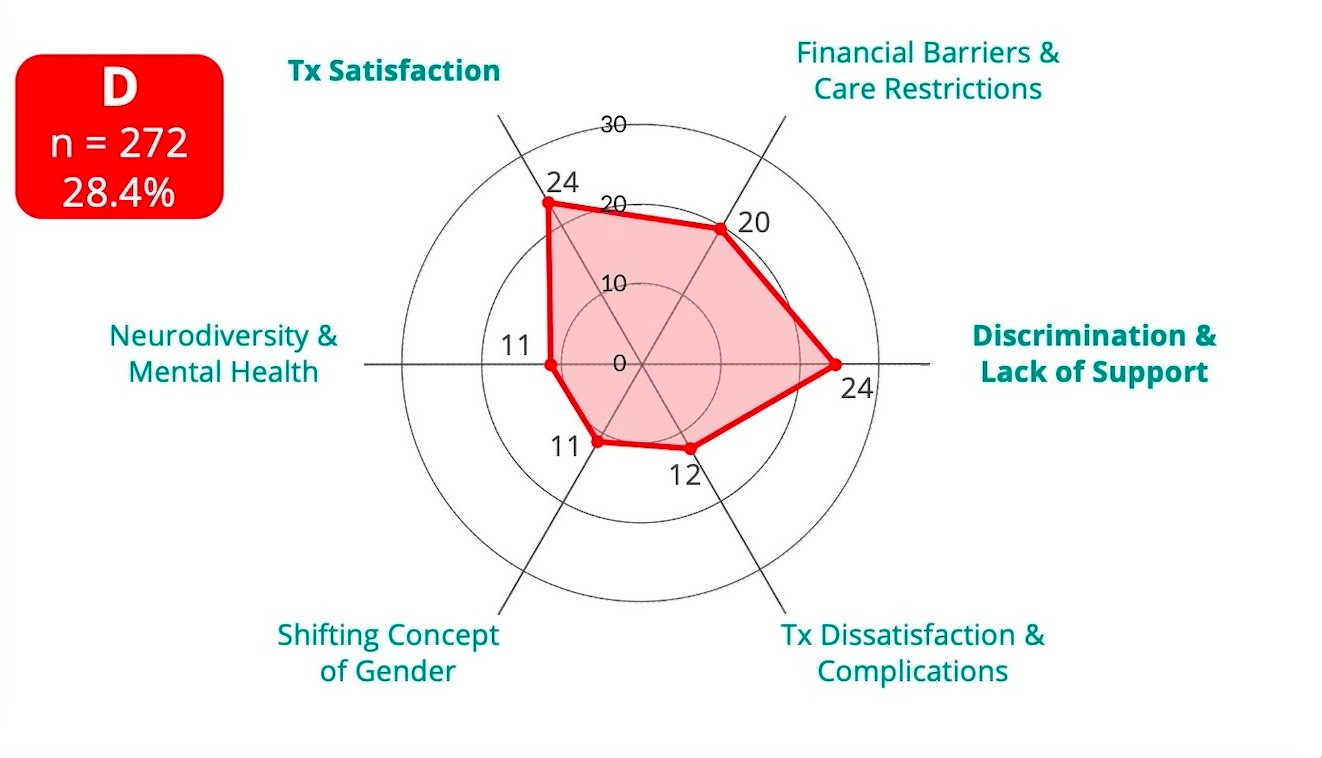

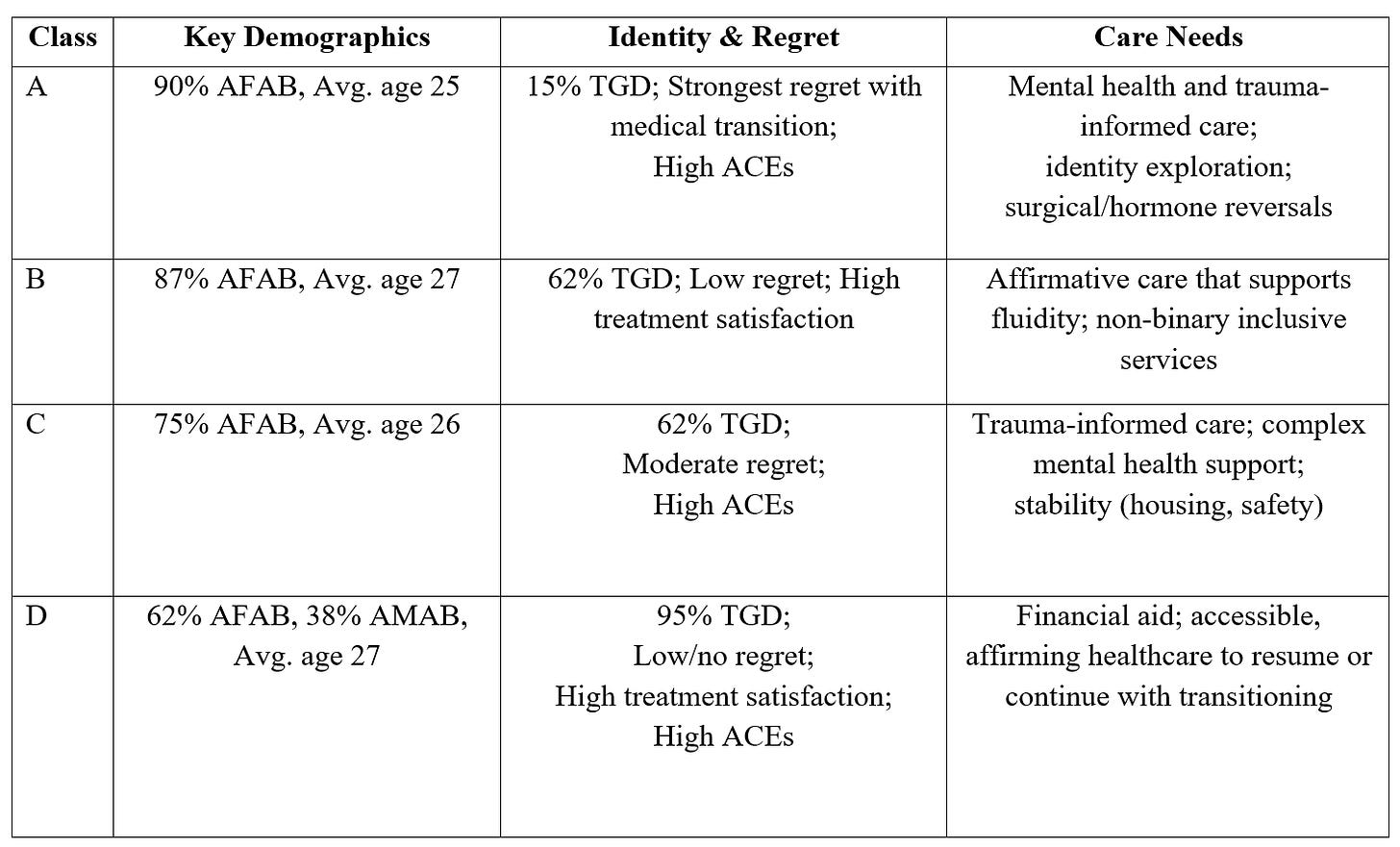

Using LCA, each of the four classes was demarcated by dimensional characteristics driving their self-reported detransition decision-making (e.g. gender minority stressors; barriers to trans healthcare, mental health concerns/neurodivergence, identity changes, etc). Below, radar plots illustrate the strength of each dimensional factors. Of the four classes, two could be broadly understood as being predominantly externally-driven detransitions, and two could be broadly understood as being moreso internally-driven. But across each of the four, the profiles show multi-dimensionality, indicating that detransition is a complex experience for anyone who experiences it.

Detransitioning with regret (Class A)

Identity evolutions (Class B)

Transition ambivalence (Class C)

Interrupted gender transitions (Class D)

This LCA highlights that detransition is not a monolithic experience. Rather, it can span changes in self-concept, mental health-related factors, gender minority stressors, treatment satisfaction or dissatisfaction, and healthcare access barriers.

Much of the analysis was aimed at characterizing unique detransition-related experiences to get a better sense of who is detransitioning and what their associated care needs may be. We also used additional tests to examine whether there were statistically significant differences across the classes (age of realizing a TGD identity, timelines of initiating social and/or medical transitions, exposure to adverse childhood experiences, recalled childhood gender identity/gender nonconformity, history of mental health diagnoses received, and so on).

Detransitioning with regret (Class A)

This group was mostly birth-registered females (90%), with a smaller number being assigned male at birth (10%). They’re the youngest of the four groups, with an average age of about 25. On average, they first began identifying as TGD around age 15. Most describe themselves today as lesbian or gay (42%) or as straight/heterosexual (16%). In fact, this is the only group where most (85%) no longer report a current TGD identity.

About one in four (26%) said they wanted to detransition but felt unable to, showing that feelings of regret were common, but taking steps to actually initiate the process proved uncertain and difficult. Among all the groups, Class A had the lowest rate of retransitioning (19% resumed transition after a temporary pause), explained by the fact they also reported the strongest decisional regret with gender transition. They also reported low satisfaction with gender-related medical treatments, and the most fluid experiences of gender identity and expression over their lives, despite being the youngest at the time of taking the survey.

Just over a third (38%) said they had a mental health assessment to support them in transition-related decisions, though nearly two-thirds (65%) had gone through a medical transition. Compared with other groups, they reported the highest levels of lifetime mental health challenges and formal DSM diagnoses—including anxiety, mood, trauma-related, obsessive, and eating disorders—they also reported high scores for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

For Class A, they predominantly reported that the decision to detransition came from within rather than outside pressures. They often cited dissatisfaction with treatment, declining mental health after transition, or shifts in their understanding of gender norms and internal self-concept.

Identity evolutions (Class B)

Like Class A, this group was also a large majority AFAB (87%), with an average age of about 26. Most described their sexual orientation as bisexual or pansexual, while a smaller number identified as straight. Many were nonbinary in this group. On average, participants realized they were transgender or gender-diverse around the age of 15.

Where Class B diverges from A is in their reports of being quite satisfied with gender-affirming medical care. At the time of the survey, 62% had a current transgender or nonbinary identity, suggesting that their experience was one of gender evolution and continued connection to gender-diversity.

Despite some changes in identity and self-concept over time, they tended to report positive experiences with transition-related treatments, high satisfaction, and few external barriers such as cost, lack of support, or discrimination. Reports of strong regret were rare in Class B, however around one in six said they had wanted to detransition but still felt unable to do so.

Two-thirds of participants had underwent medical transition, and about a third reported gender-related surgery. Most had access to assessment or decision-making support as part of their process of starting a gender transition.

Transition ambivalence (Class C)

Members of Class C often showed conflicted relationships with their gender transitions. The group was composed mostly of transmasculine, AFAB individuals (76%), but with slightly greater portion of transfeminine, AMAB individuals typed into this subgroup compared to A and B. They had a mean age of 25.5 years.

About two-thirds (66%) had undergone some form of medical transition, but their evaluations of treatment diverged from positive to strongly dissatisfied. At the time of the survey, 62% reported a current trans or nonbinary identity, but members reported a notably high level of identity fluidity, with half (47%) reporting they had already retransitioned at some point. About 29% said they wanted to detransition but said they felt unable to take steps.

Overall, their pathways were complex and ambivalent, shaped by both external pressures—such as discrimination, romantic rejection, and lack of social support—and internal factors, including mental health challenges, and evolving gender identities.

Interrupted gender transitions (Class D)

The main way to understand this detransition experience is as a temporary transition interruption, usually involuntary. This type of experience is often mediated by external barriers such as discrimination, limited access to gender-affirming care, or lack of support—not by changes in identity or self-understandings. They predominantly reported satisfaction with treatments and no or very low decisional regret.

Compared to the other three groups, Class D contains the largest portion of trans women and other participants who were assigned male at birth (37%), with 62% being trans men or nonbinary people born female. On average, participants realized their transgender or gender-diverse (TGD) identity at age 14—slightly younger than the other groups. Though, they typically began medical transition at older ages than the other groups, with 62% having ever started a medical transition.

At the time of the survey they were an average age of 27 years. Nearly half in Class D were bisexual (48%) while 8% identified as straight. Most participants (95%) continued to identify as TGD, the highest of all the classes.

They generally reported decision-making supports, with a majority reporting access to assessments or talk therapy.

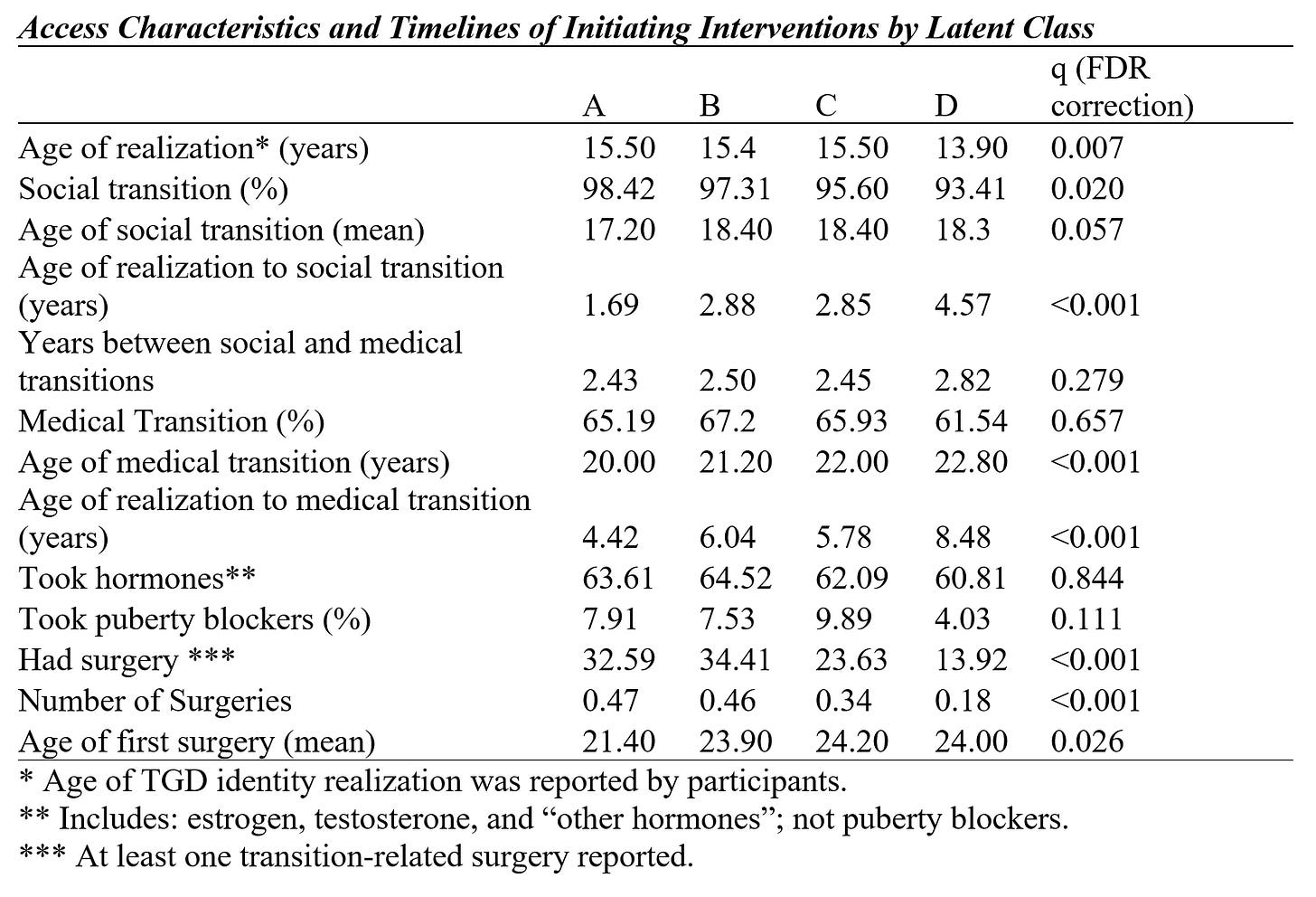

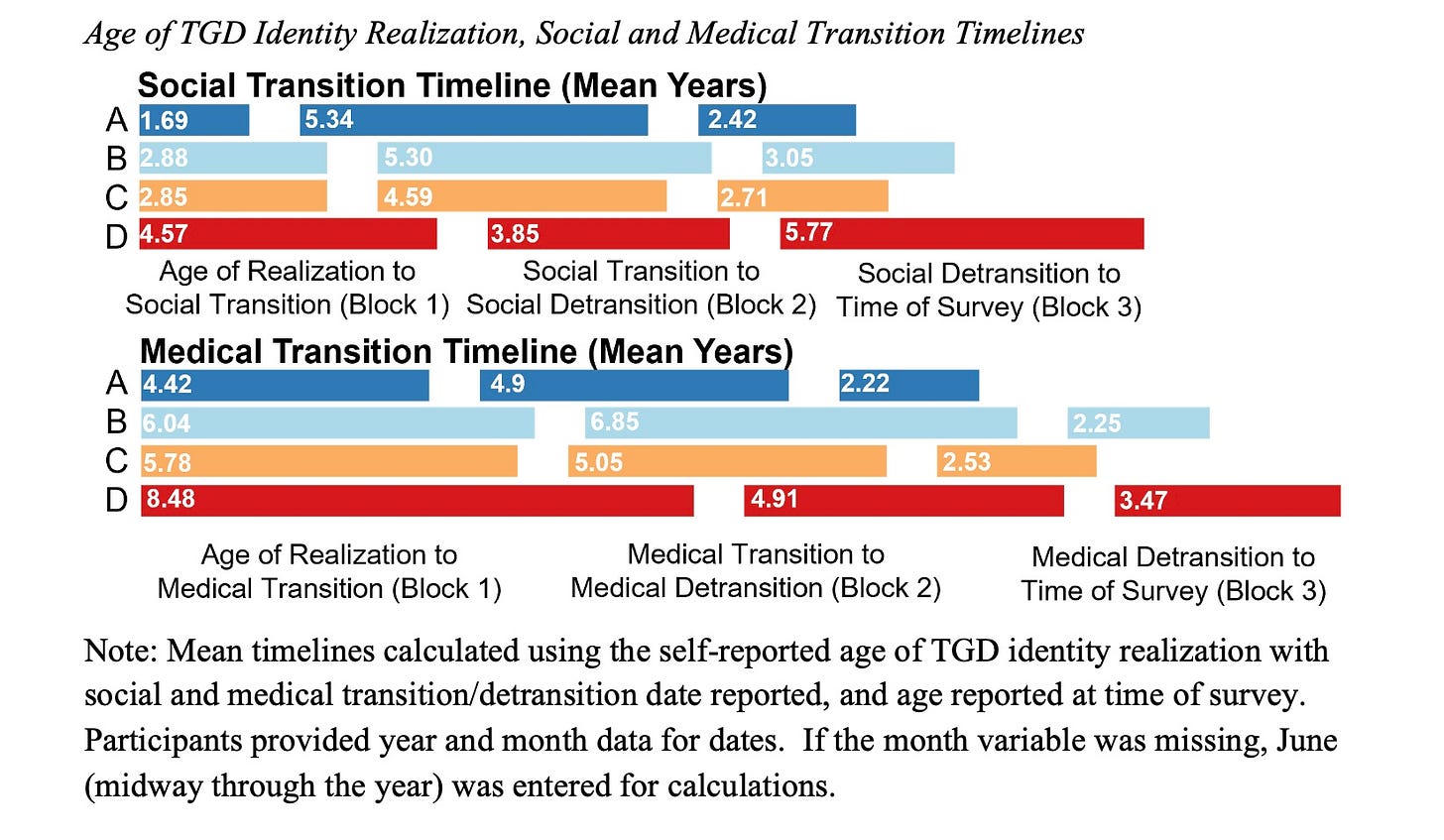

Timelines to transition and detransition

Zooming in further, the four groups reported some unique transition-related trajectories, life experiences, and timelines. (The paper itself has 7 tables and 8 figures, so it’s really quite jam-packed with important data).

The average timeline between when participants started to think of themselves as transgender/nonbinary, starting to transition, and then starting to detransition, ranged from several months to well over 15 years. Overall, we see quite a longitudinal pathway of identity development among this group of LGBTQ+ young people. There was also some class variation observed, with Class A having shorter timelines.

Shifting grounds and moving beyond regret

When promising medical interventions seem to make life better for many, yet unexpectedly more complicated for others, what is the ethical way to respond? Governments, hospitals, medical associations and clinicians around the Western world have been grappling with this question since the visibility of detransition made it unavoidable several years ago. Anecdotal reports of detransition have since become a flashpoint in culture war debates, while actual patient experiences have remained under-researched.

The DARE study is one of the first large-scale LGBTQ+ community research studies specifically designed to include detransitioners, to learn more about these experiences since access to transition-related care was made more widely available over the last 10-15 years. One major strength of the study was that it included a large and diverse group of people located across the U.S. and Canada who brought diverse life histories and perspectives on their gender transitions—those with satisfactions, ambivalence, as well as many with strong regrets. Learning about and responding to the full range of post-transition lived experiences is fundamental to promoting flourishing among gender-diverse people, including for those who wish to discontinue treatment for gender dysphoria.

So far, the DARE study is one of the most detailed studies to look into TGD young people’s gender identity development over time and to include a focus on factors influencing their detransitions.

The LCA approach helped us as researchers to pick out patterns from the data, such as looking for key demographics, early life experiences, and clinical and social contexts that may connect to outcomes like satisfaction, dissatisfaction, regrets, or to involuntary detransitions. While this was one of the key aspects of the study design, it’s also important to keep in mind that in the real world the four groups identified may not be so completely distinct from each other. Transgender, nonbinary, and detransitioned people are all part of a broader gender minority population that share many commonalities, including a need for human dignity, social inclusion, and access to healthcare rooted in rigorous research.

Comments are open.

See also:

If anyone would like a pdf copy of the article, please email me:

kinnonmk @ yorku.ca

Thanks for this very thoughtful and grounded discussion of a complex phenomenon. The references / links are very much appreciated.