Groundbreaking Analysis Upends Our Understanding of Psychiatric Holds

In situations where some physicians would admit involuntarily but others would not, holding patients against their will leaves them worse off.

When someone is experiencing a mental health crisis and poses a risk to themselves or others, involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, also known as psychiatric hold or involuntary commitment, is a common intervention. The intention behind this approach is straightforward. It’s supposed to protect individuals in a state of vulnerability. But does it really achieve this goal beyond the immediate period of confinement in the hospital?

The impact of involuntary psychiatric hospitalization has been very difficult to study empirically because randomization to involuntary treatment is not permitted for ethical reasons, and observational data is inherently confounded because the patients who are admitted involuntarily and those who are not are different from each other to begin with, and differences in outcomes seen in observational studies cannot be attributed to the effects of hospitalization.

A new landmark analysis by Natalia Emanuel, Pim Welle, and Valentin Bolotnyy uses a creative, quasi-experimental approach and challenges some of our basic assumptions about the effectiveness of involuntary hospitalization. They leveraged the random assignment of physicians to assess outcomes and focused on situations where physicians disagree as to whether hospitalization is warranted (“judgment call cases”). They found that involuntary psychiatric hospitalization significantly increases the likelihood of death by suicide or overdose and the likelihood of facing criminal charges in the months following the hospitalization in this scenario.

“A Danger to Self and Others: Health and Criminal Consequences of Involuntary Hospitalization” has been published as a working paper, number 1158, in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports. In addition, the team has also published a plain language summary and FAQ. The plain language summary is outstanding. I could probably have just linked to the document and jumped straight to my comments rather than summarize myself.

The study focuses on Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, US, home to Pittsburgh, where detailed data have been collected since 2014, allowing for a comprehensive look at the impact of involuntary hospitalization. In the U.S., involuntary hospitalization is a common occurrence—about 1.2 million cases each year, roughly matching the entire prison population of the country. Every state has laws permitting this intervention, with broadly similar commitment criteria (focusing on suicidality, violence, and grave disability), though procedures differ.

The usual process is that after referral, often from family, police, or healthcare providers, individuals are evaluated by emergency department physicians who decide whether hospitalization is necessary. In Pennsylvania, a physician can hold an individual for up to 5 days, after which court intervention is required to extend hospitalization.1

The outcomes for this population are terrible, regardless of psychiatric hospitalization.

“20% of evaluated individuals [in Allegheny County] die within five years after the evaluation [for psychiatric commitment]—a rate that is higher than that for individuals exiting jail, enrolling in homeless shelters, or living with severe mental illness in general. Further, 24% are charged with a criminal offense within a year of evaluation (Welle et al., 2023).” [Emanuel, et al. 2025]

This study uses comprehensive administrative data from Allegheny County, including records of involuntary hospitalizations, criminal charges, suicide and overdose deaths, healthcare utilization, employment, and shelter use. Data from Medicaid, state employment records, and medical examiner reports provided extensive demographic and health-related insights, crucial for rigorous analysis.

The researchers used a sophisticated quasi-experimental approach, called an “examiner research design.” They took advantage of the quasi-random assignment of patients to different examining physicians, who differ in their inclination to hospitalize patients. This method allowed researchers to isolate the effect of hospitalization itself on patient outcomes.

“We use the fact that which examining physician assesses a given patient is as good as random and that physicians differ greatly in their tendency to uphold petitions for involuntary hospitalization. In a randomized experiment, a patient is randomly assigned to treatment or control. In our context, a patient is randomly assigned a physician for an exam, and that physician may have a high or low tendency to hospitalize patients. In a randomized experiment, a subject can be “lucky” or “unlucky” in that they get heads or tails and subsequently receive either the treatment or control, and in an examiner design a subject can be “lucky” or “unlucky” in that they are assigned to a more or less discerning examiner. We use this variation in examiner behavior to untangle causal effects.

Specifically, we compare outcomes among patients who were assessed by physicians who have a high tendency to hospitalize to the outcomes among patients who were assessed by physicians who have a low tendency to hospitalize. The comparison yields estimates about the effect of hospitalization on those individuals who would have been hospitalized by the physician with a high tendency to hospitalize but not by the physician with a low tendency to hospitalize.” [plain language summary by the authors]

With regard to the physician tendency to hospitalize, the hospitalization rate in the sample ranged from 11% to 100%. That’s quite a spread! I imagine most people underestimate this range.

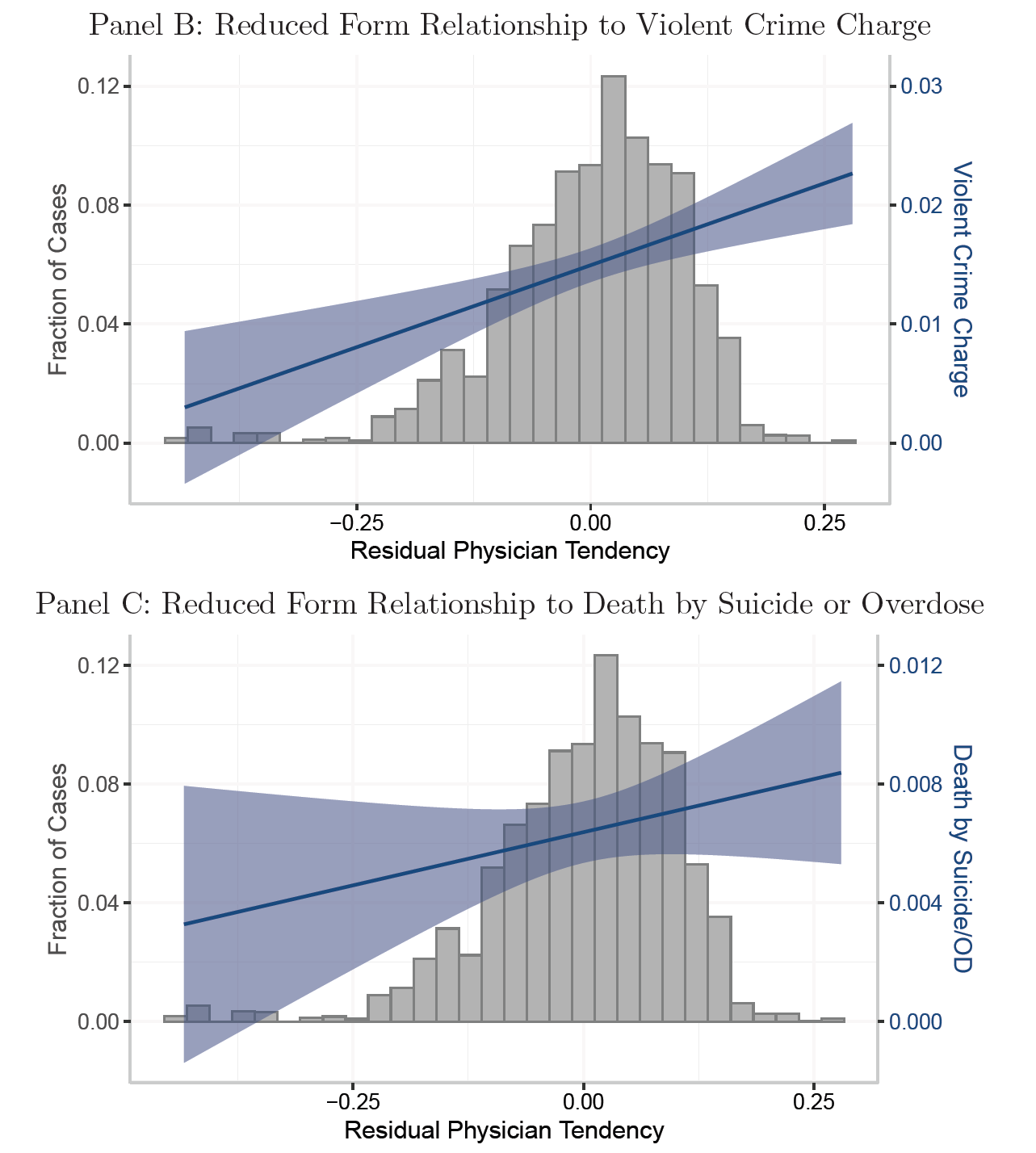

“Our sample contains 424 physicians at 14 different hospitals… Our residualized measure of physician tendency to hospitalize ranges from -0.427 to 0.271, with a standard deviation of 0.098. The lowest rate of hospitalization that one physician has is 11%, while 46 physicians hospitalize all of the cases they evaluate.” [Emanuel, et al. 2025]

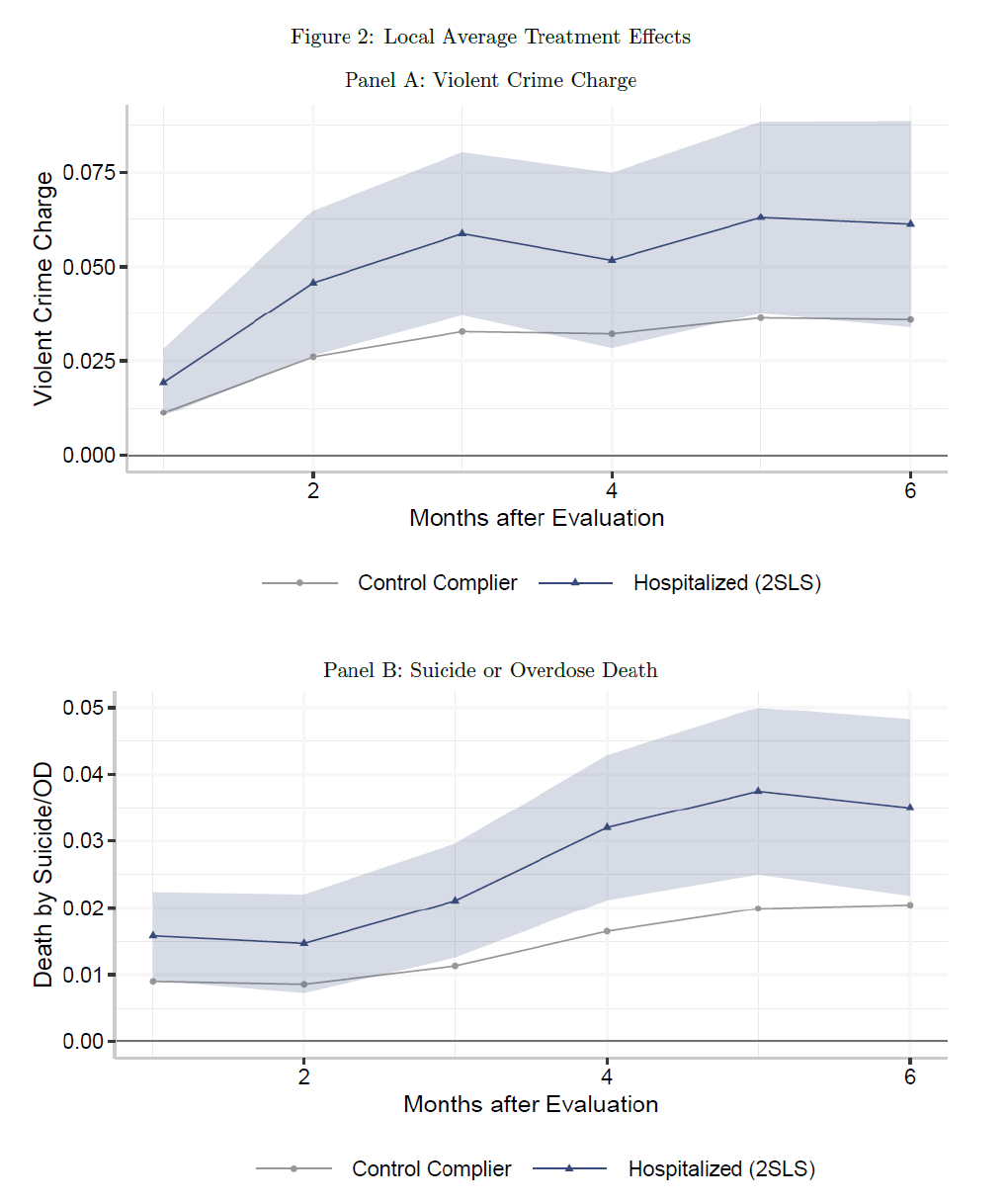

For judgment call cases, involuntary hospitalization made things worse. Over a period of three months, these patients were significantly more likely to experience the very harms hospitalization aims to prevent. The likelihood of being charged with a violent crime increased from a baseline of 3.3% to 5.9%. Additionally, the risk of suicide or drug overdose death nearly doubled, rising from 1.1% to 2.1%.

“For being charged with a violent crime, our reduced form estimate finds that a 10 percentage point increase in a physician’s tendency to hospitalize is associated with a 2.6 percentage point increase in being charged with a violent crime within the following 3 months.” [Emanuel, et al. 2025]

“A 10 percentage point increase in a physician’s tendency to hospitalize yields an increase in the probability of death in the next three months of 0.98 percentage points.” [Emanuel, et al. 2025]

Important caveats:

The estimate applies only to individuals where one doctor might uphold and another doctor might deny the petition (“compliers” or “judgment call cases”). Authors estimate that roughly 43% of those evaluated for involuntary hospitalization in their sample fall into this group. Compliers were less likely to have a prior history of mental illness, more likely to have prior criminal charges and prior emergency department visits, and more likely to be referred by a family member.

Analysis relies on data from one county in Pennsylvania, and how well these results extrapolate to other geographies remains to be seen.

Results are relevant only to those who underwent evaluation for involuntary hospitalization for the first time. Authors focus on this population because individuals who experience repeat evaluations may not be assigned an evaluating physician at random.

Analysis was restricted to adults in the age range 18-65. (Involvement of parents, guardians, and caregivers in children and elderly introduces its own considerations.)

Results don’t apply to voluntary psychiatric hospitalization.

Several assumptions are necessary for the analysis to be valid.

“These are: (1) relevance: physicians’ tendencies to hospitalize other patients are associated with hospitalization of a given individual, (2) random assignment: physicians are (conditionally) randomly assigned to involuntary hospitalization cases, (3) monotonicity: patients who would be hospitalized by physicians with a low tendency to hospitalize would also be hospitalized by physicians with a high tendency to hospitalize and vice versa, (4) exclusion restriction: physician assignment impacts outcomes only through hospitalization.”

Authors spend considerable space in the paper testing or discussing the validity of these assumptions.

Why would an intervention intended to help end up doing harm? The researchers offer and investigate several plausible explanations. Involuntary hospitalization can be a deeply disruptive experience. Patients are often forcibly taken by police, held for days, and sometimes medicated without consent. Such experiences might isolate individuals from their support networks, including family and existing mental health providers. Furthermore, hospitalizations can disrupt employment and increase homelessness, causing a spiral of instability that exacerbates rather than alleviates mental distress.

In analyses conducted by the authors, involuntary hospitalization led to reduced earnings and increased shelter usage, suggesting economic and social instability as key mechanisms. Hospitalization did not appear to affect medication adherence or outpatient mental health care utilization, positively or negatively.

“We find evidence that involuntary hospitalization causes destabilization, as evidenced by a decrease in employment and earnings, as well as an increase in shelter usage among those who had not used a shelter in the prior year. We do not find evidence to suggest that a decrease in drug tolerance is causing deleterious effects. We also do not find evidence that hospitalization meaningfully alters utilization of continuing care, such as outpatient mental health services or adherence to prescribed medications.” [Emanuel, et al. 2025]

Emanuel, et al. conclude that involuntary hospitalization as currently practiced (in Allegheny County specifically, but presumably representative of larger national practices) may be counterproductive for many individuals at the margin. This warrants caution in expanding involuntary hospitalization policies and emphasizes the importance of developing better alternatives and decision-support systems to manage psychiatric crises.

“Despite the areas not tackled in this paper, the results we present have important policy implications. As policymakers consider expanding involuntary hospitalization, our local average treatment effects provide insight into what would happen if physicians making the decision to hospitalize were slightly more expansive in who is hospitalized. The results we present suggest that expanding involuntary hospitalization in our setting is unlikely, without additional changes, to reduce danger to others or to the patients themselves.” [Emanuel, et al. 2025]

I’ve been aware of these results for almost a year now. I was fortunate that I was a panelist on the conference panel at the 2024 ISPS meeting where Pim Welle presented the preliminary results for the panel to discuss. When I first saw the findings, I was incredulous. I felt sure that there must be a confounder at play, that the worse outcomes at 3-6 months must be a reflection of some factor other than hospitalization. But after spending a substantial amount of time looking at the methods (and asking Pim a lot of questions!), I realized that the analysis is quite rigorous and robust, and there is no way to explain the results away. I am now of the view that the results are genuine. Of course, I’m open to changing my mind should future analyses or replication efforts show otherwise.

Here’s how I would describe the clinical takeaway of the findings:

In situations where a person undergoing an evaluation for involuntary psychiatric admission can reasonably be discharged rather than involuntarily admitted, i.e., in situations where some clinicians will choose to involuntarily hold the patient but others will not, it is better to discharge the person than commit them.

This is the opposite of conventional wisdom. This is the opposite of what most psychiatric clinicians are actively taught, including clinicians such as psychiatric social workers who often perform assessments in emergency rooms. Clinicians are trained to be conservative, to be risk-averse, to be “better safe than sorry.”When it comes to psychiatric commitments, the clinical culture in the United States is to involuntarily admit a person if one is in doubt.

The findings by Emanuel and colleagues indicate that we should be doing the reverse. We should only be committing the patient if we are certain that the person needs involuntary care and that this is a situation where other clinicians would also agree with the necessity. If we go by the better-safe-than-sorry, admit-if-you-are-in-doubt approach, we will likely subject people to harm.

Why do some clinicians choose to admit when their colleagues would discharge?

I believe a lot has to do with physician perception of liability and the degree of risk any particular physician is willing to take on. Suicide and violence risk are nebulous. Imminent risk is also different from chronic risk, and furthermore, no method of risk assessment comes anywhere close to reasonable accuracy. Clinician assessments of risk therefore vary widely, and so do thresholds of comfort with liability.

In many cases, the true purpose of involuntary hospitalization is risk management and liability control rather than meaningful improvement in clinical outcomes. You may think I am being cynical, but I am being frank, as a psychiatrist who is intimately familiar with what happens behind the scenes. In such situations, physicians are not involuntarily admitting the patient because they are convinced that the risk of harm to self or others will be meaningfully ameliorated with hospitalization. Instead, they involuntarily admit the patient because they believe that, in the unlikely event of a negative outcome, their decision to admit will shield them from liability.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb writes in Skin in the Game:

“The legal system and regulatory measures are likely to put the skin of the doctor in the wrong game… A doctor is pushed by the system to transfer risk from himself to you, and from the present into the future, or from the immediate future into a more distant future.” (2020, p. 64)

Physicians and hospitals are under pressure from two sources: a) risk of lawsuits and complaints to the medical board, and b) scrutiny from regulatory and accrediting agencies (e.g., the Joint Commission and CMS.)

They face potential liability or scrutiny if a patient they didn’t admit dies by suicide, or engages in an act of violence or experiences some other tragedy. There is liability if a patient dies under their care or elopes. There is liability if a patient dies shortly after discharge. Or if they get readmitted shortly after discharge.

But there is no liability or penalty if a person is at higher risk of suicide or incarceration 3 months later due to their hospitalization, if their admission is very traumatic for them, if they lose their job, if they lose their housing, if they lose their family support, if something happens to their pets, or if they lose their trust in the medical system, etc, etc.

The system puts the skin of the doctor in the wrong game when it comes to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization.

Considerations of liability influence both decisions to involuntarily admit people and the experience of care on the inpatient unit. Psychiatric hospitals are currently optimized around considerations of risk and liability (and the bureaucratic needs of accrediting institutions). This is reflected in their architecture, furniture, layout, admission processes, nursing monitoring protocols, patient privileges, etc. Psychiatric hospitals would look very different if they were optimized for the therapeutic benefit and psychological well-being of patients and to ensure autonomy, comfort, dignity, and social connection.

Remedying this requires changing incentives for hospitals and physicians, such that practices are truly oriented around patient-centered outcomes, and changing the culture of risk and liability, such that physician decisions to involuntarily admit are not driven by perceptions of liability.

We need to recognize the disability and disruption that accompanies mental illness; it is not a fiction, and systems of care are a necessity. Attempts to reduce involuntary psychiatric hospitalization without creating alternatives are not likely to end well. The good news is that many such alternatives exist, such as open-door units, crisis stabilization units, crisis houses, peer respite centers, partial hospitalization programs, intensive outpatient programs, and home hospitalization. These alternatives remain woefully underfunded and underdeveloped.

I don’t foresee these alternatives as eliminating involuntary psychiatric admissions entirely, but they reduce the default reliance on involuntary care in emergency contexts, and for people at the margins, this can be a difference of life and death.

Seriously… in situations of reasonable doubt and disagreement, it is better to discharge the patient than involuntarily hold them. I have always believed this for ethical reasons, out of respect for personal autonomy. Now, thanks to research by Emanuel, Welle, and Bolotnyy, I can believe so for empirical reasons as well.

See also:

“Out of 16,630 evaluations, 78% result in a decision to hold an individual for up to 5 days; the others are released. Physicians petition for 51% of the emergency holds to be extended (39.4% of the initially evaluated cases). Of those extension petitions, 73% are upheld by the magistrate, keeping the patient hospitalized for up to 20 days total (28.6% of the initially evaluated cases). Put differently, 8,150 or 63.1% of the initial involuntary hospitalizations do not extend beyond 5 days. Of those evaluated, 6.3% are petitioned to be held up to 90 days and 0.8% are petitioned to be held up to 180 days.”

Thanks for sharing this study. I've worked extensively as both a crisis evaluator and on inpatient psychiatric units and you're assessment is spot on. Involuntary inpatient psychiatric hospitalization is so disruptive to people's lives, and, particularly in smaller communities, very stigmatizing. Not only is the person getting the message that they are "dangerous" but now they have also come to the attention of law enforcement.

I have watched people who have never had any contact with the legal system be handcuffed in order to be placed in the police car for transport to the psychiatric placement. When I would ask the police officer, "are the handcuffs really necessary," they would cite policy and safety.

Many people refuse voluntary psychiatric admission to inpatient units for precisely the reasons you mention. They have jobs, children, pets, other responsibilities that prohibit them from being away for days at a time. When those crisis moments hit, although they are suffering, they are very cognizant of these responsibilities. Wouldn't it be wonderful if we had a system that was designed to give a person a "time out?" Where they could stay for a few hours/days, receive psychiatric care, move through the initial hours of the crisis with support and in a safe place, and then return to their responsibilities.

For many people, suicidal ideation is a fleeting event. Something has occurred that has so overwhelmed their ability to cope, that taking their own life feels like a viable option. For many people, these moments pass, and with support, they stabilize and move forward with their lives. We need to set up less intrusive systems, that invite people to use them voluntarily, so that we don't have to resort to involuntary hospitalization in our effort to "keep someone safe," and do more harm than good.

upends “our” understanding… this, I guess, being an exclusive “our”. this does not upend my understanding! I’m glad the authors were able to develop an empirical method to demonstrate what any involuntarily committed person already knows. I hope more studies like this can be done so that the scientific consensus can be shifted, and then, hopefully, normative clinical practice can be shifted as well.