ADHD Beyond Stimulants, and Stimulants Beyond ADHD

Your brain on stimulants vs your brain on ADHD

There is a peculiar tendency I’ve noticed where people try to understand what ADHD is through the effects of stimulant medications and correspondingly there is an inverse tendency where they try to determine the scope of the appropriate clinical use of stimulants through the boundaries of ADHD as a diagnosis.

The first tendency is particular evident among critics of ADHD who often use evidence of nonspecific psychoactive effects of stimulants to argue against the reality of ADHD as a medical problem, such arguing that individuals with ADHD are just bored individuals trying to medicate their tedium or pursue some misguided ideal of enhancement (“of course you are more focused on Adderall; it’s basically meth, duh.”)

The second tendency is more obvious among clinicians who would only consider formally recognizing a person’s attentional difficulties and prescribing a stimulant if the patient can prove they meet stringent criteria and had diagnosable ADHD as a kid, and among patients who want to make a case that they stand to benefit from stimulants (or want to justify continued use) by proving that they indeed have ADHD.

Given how frequently I encounter this sentiment, it’s worth going into some detail of the mismatch between the “ADHD brain” and the “brain on stimulants.”

ADHD is not a disorder any specific brain network, but stimulants have specific effects on brain networks

A recent blockbuster study in Cell provides a good starting point for this discussion. “Stimulant medications affect arousal and reward, not attention networks” by Benjamin Kay et al. (2025) is a rigorous study showing that stimulants change functional connectivity of brain in networks associated with arousal, in networks associated with salience and reward, but they do not affect canonical attention networks, regardless of whether the person has ADHD.

The first thing to appreciate is the discrepancy between the clinical vs cognitive psychological meaning of “attention.” Michael Halassa explains it beautifully in his discussion of the study on his substack, so I’ll just quote him:

“Now onto the second issue: “attention”. This word means different things in different contexts. In ADHD diagnostic criteria, “inattention” means not staying on task, getting distracted, forgetting instructions. These are problems with sustained engagement and persistence. By contrast, in cognitive psychology, attention refers to selective amplification of relevant information, like covertly allocating processing resources to a small patch of visual space (e.g. in a Posner cueing task; see figure below) or selectively increasing focus to one out of several conversation in a crowded room without actually moving your head (the cocktail party problem). That is not what people refer to when they are discussing “attention” in ADHD.

The imaging results therefore line up pretty nicely with the clinical meaning of attention in ADHD, which is about sustained engagement rather than selective processing. Whether stimulants actually help with selective attention in the cognitive psychology sense is not particularly clear because we lack sufficiently high powered studies looking at it from that perspective. That said, it is also unclear whether people with ADHD have selective attention deficits beyond those related to arousal and task engagement. Maybe a subset exists, but that hasn’t been demonstrated empirically as far as I’m aware.”

Let me put it in a different way. Stimulant medications do not directly influence the canonical attention networks (dorsal and ventral attention networks and frontoparietal network), but neither is ADHD a disorder of attention networks. ADHD has no special relationship to attention networks. Or to reward/salience networks, for that matter. In fact, ADHD is not definable as a disorder of any specific brain network at all, even though it involves subtle, distributed connectivity differences across the whole brain.

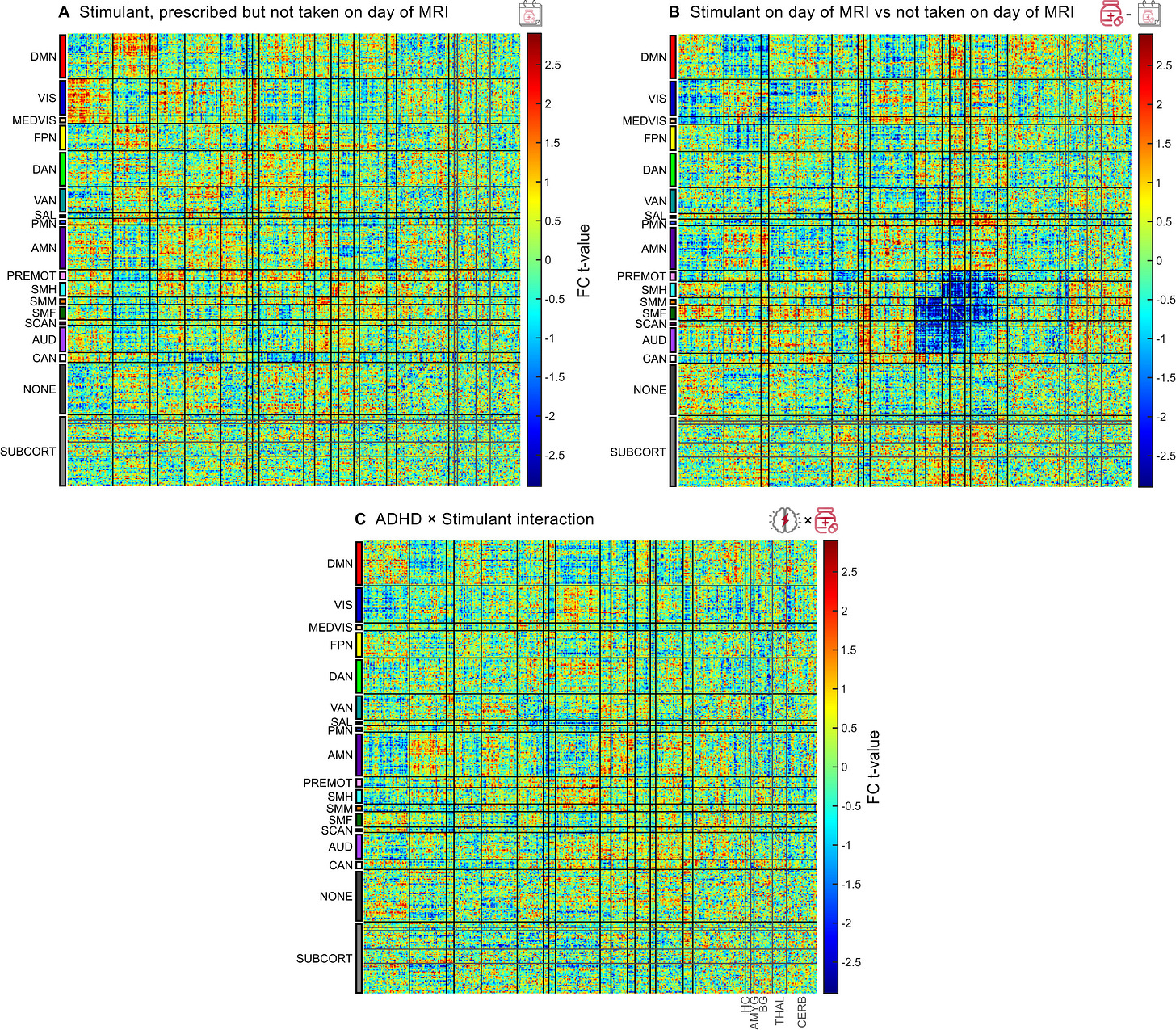

Take Figure S6 from the Cell paper

This type of diagram is called a connectivity matrix and it shows statistical relationships between brain connections and some variable of interest. The figures here are intended to distinguish acute stimulant effects on brain connectivity from effects of ADHD diagnosis plus any effects of chronic stimulant use.

Panel A represents children prescribed stimulants but who didn’t take them on scan day. The connectivity pattern is mostly noisy and random with no clear structure. There is no clear brain “fingerprint” of brain connectivity in ADHD kids off medication.

Panel B represents children prescribed stimulants and who took their medication on scan day. There is a clear pattern here, particularly a clear blue square in the salience/motor network regions.

Panel C is about ADHD × stimulant interaction, testing whether stimulants affect ADHD brains differently than non-ADHD brains. The pattern is again relatively weak/noisy with no strong structured effects. This means that stimulants produce similar neural effects regardless of ADHD diagnosis, and the therapeutic benefit in ADHD may come from the same brain circuit changes that occur in everyone, but these changes may be more functionally relevant for people with ADHD.

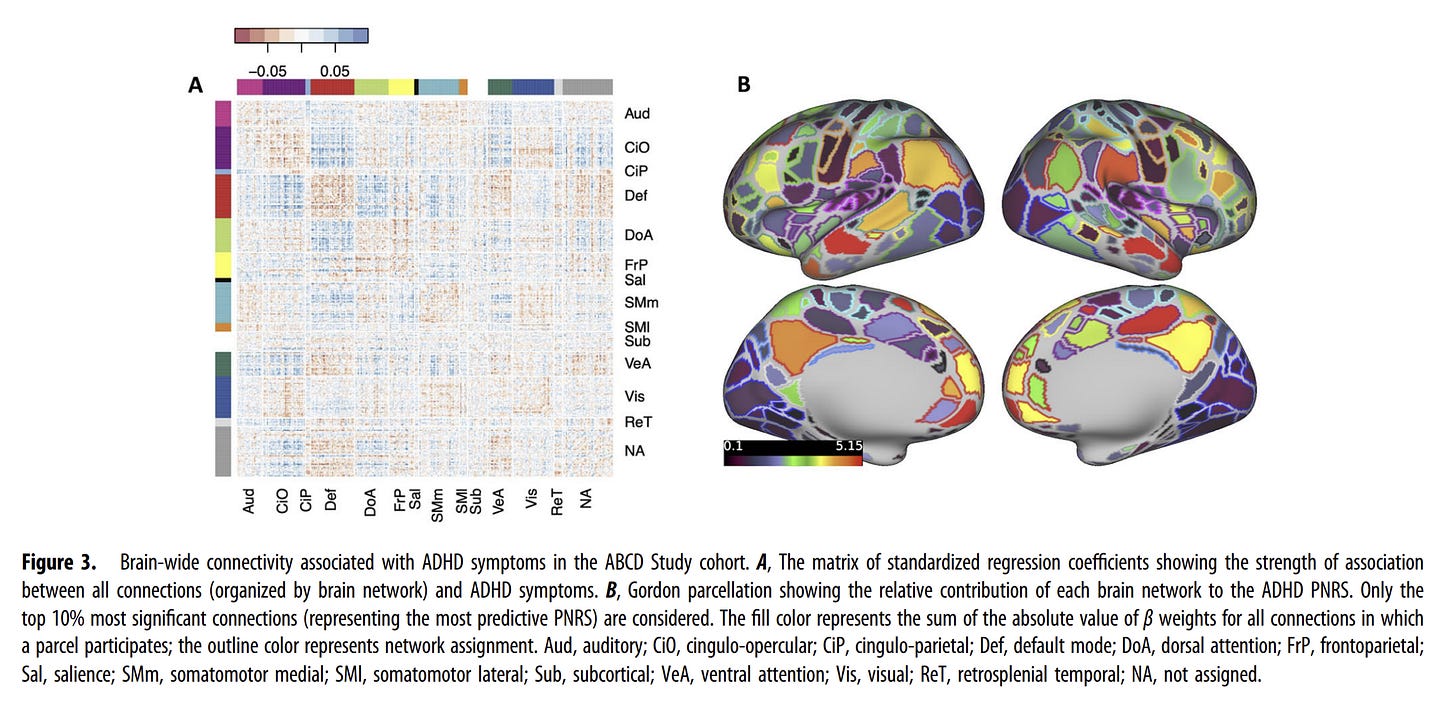

Consider this connectivity matrix from the 2024 paper, “Cumulative Effects of Resting-State Connectivity Across All Brain Networks Significantly Correlate with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms” in the Journal of Neuroscience:

Figure 3A above shows all brain connections associated with ADHD symptoms, and it shows relatively diffuse, weak patterns with no dramatic focal effects of the sort seen with stimulants. Figure 3B (brain surface map) shows reasonably widespread contribution across multiple networks to the ADHD polygenic risk score, suggesting ADHD is associated with brain-wide connectivity differences. In the same paper, researchers also identify the most predictive connections, which form a distributed pattern across networks.

I am sharing all this to reinforce: ADHD is not a clinical syndrome associated with characteristic alterations in attention networks or salience network or some other specific network. It involves subtle, brain-wide differences in connectivity. It is not yet clear whether there are any distinct subtypes of ADHD that correspond more strongly to specific brain networks.

Stimulants, on the other hand, have a clear pattern of effects on brain circuit connectivity. They change functional connectivity in action regions consistent with arousal, in salience regions consistent with reward, reverse the behavioral and brain effects of sleeping less, but they do not affect canonical attention networks.

Stimulants make boredom tolerable and help undertake unrewarding tasks (the paradoxical calming effect)

Stimulants increase effort, persistence, alertness, and perceived reward, and their beneficial clinical effects seem in part to arise from sustaining engagement with tedious or unrewarding tasks. This also helps explain the paradox that stimulant medications that otherwise increase psychomotor activity reduce hyperactivity in ADHD.

Benjamin Kay and colleagues write in the Cell paper,

“The seemingly paradoxical effect that stimulants can reduce hyperactivity may instead be related to their dopaminergic effects on salience processing. The second largest stimulant-related differences in FC were in SAL/PMN, which together are thought to encode anticipated reward/aversion and thus influence the decision to persist at a task or switch to a more rewarding task. Aspects of ADHD hyperactivity could be associated with searching for more rewarding actions and thus better understood as motivational rather than motoric. We hypothesize that stimulants reduce task-switching and thus appear outwardly to facilitate attention by elevating the perceived salience of mundane tasks (e.g., math homework) through their effect on SAL, boosting persistence and effort without affecting cognitive ability.”

Stimulant medications make boring tasks (like math homework, spreadsheets, laundry) feel more important and worthwhile. This helps people stick with these tasks longer and put in more effort. Mundane tasks feel more worth doing, so people are less likely to abandon them for something more interesting.

This framing can appear to downplay the therapeutic significance of stimulant medications for some readers. It is worth emphasizing that stimulant medications show associations with positive clinical outcomes in the treatment of ADHD that other psychiatric medications can only dream of. In various observational and cohort studies, treatment of ADHD with stimulants reduces accidental injuries, traumatic brain injuries, substance abuse, educational underachievement, bone fractures, sexually transmitted infections, criminal activity, teenage pregnancy, and mortality.

ADHD x Stimulant Clinical Interactions

In the Cell paper, children with ADHD on stimulants demonstrate cognitive performance that is significantly better than their unmedicated ADHD peers and comparable to healthy children. Their school grades improve to match those of children without ADHD, and they show significant improvement on both the NIH Toolbox (a battery of cognitive abilities) and n-back task (a specific working memory test) accuracy measures, reaching the performance level of healthy children. Like all children taking stimulants, they also exhibit faster reaction times on the n-back task. Stimulants also appear to rescue the negative effects of insufficient sleep on academic grades in this group.

Children with ADHD who are not taking stimulants, their cognitive performance is significantly impaired across multiple domains. School grades are substantially worse than their peers, and they score significantly lower on the NIH Toolbox. Their accuracy on the n-back working memory task is also significantly reduced. Their reaction times on the n-back task show no significant difference from healthy children.

Children who are taking stimulants but do not meet stringent criteria for ADHD show the distinctive pattern of brain connectivity changes with stimulant treatment without corresponding cognitive improvement on NIH Toolbox and n-back. Despite stimulant-induced brain changes in arousal and salience/reward networks, their cognitive performance shows no improvement over healthy children not taking stimulants. School grades, NIH Toolbox scores, and n-back accuracy all remain unchanged. The only measurable difference is a faster reaction time of approximately 100ms on the n-back task, an effect shared by all children taking stimulants regardless of ADHD status. This replicates something we already know, stimulants are not cognitive enhancers in healthy individuals.

Healthy children not taking stimulants serve as the baseline reference group, demonstrating “normal” performance across all cognitive measures. Within this group, sleep duration emerges as a significant factor affecting performance. Children who obtain more than 9 hours of sleep per night perform significantly better on school grades, NIH Toolbox scores, and n-back accuracy compared to those with less sleep.

Clinical benefits of stimulants therefore depend on baseline status. For children with ADHD, stimulants have a clear therapeutic effect, “normalizing” their performance to the level of healthy peers across multiple cognitive domains, despite the absence of a normalizing effect seen in brain connectivity patterns. In contrast, non-ADHD children show no cognitive enhancement beyond typical performance levels (stimulants are not “smart drugs”). Stimulants can temporarily compensate for the cognitive effects of inadequate rest, though this should not be viewed as a replacement for proper sleep. All children taking stimulants, regardless of ADHD diagnosis, respond approximately 100ms faster on the n-back task.

Take this 2008 study in Journal of Clinical Psychiatry by Biederman and colleagues. They compared three groups of people on various thinking and attention tasks. People with ADHD not taking stimulant medication. People with ADHD actively taking stimulant medication. People without ADHD (the comparison group).

People with ADHD who weren’t taking medication scored worse than people without ADHD on almost everything tested:

Overall performance

Working memory (holding information in your mind)

Interference control (ignoring distractions)

Processing speed (how quickly you think)

Sustained attention (staying focused)

Verbal learning (remembering words and language)

People with ADHD who were taking stimulants still scored worse than people without ADHD on some things: overall performance, interference control, processing speed.

People with ADHD on medication scored better than those not on medication in two specific areas: sustained attention and verbal learning.

The details vary from study to study, but I think this overall pattern is important: Stimulant medications help people with ADHD improve their ability to stay focused. However, people with ADHD continue to have difficulties in many areas of their cognition that are not remedied by stimulants. There is more to ADHD than is what is addressed by stimulants.

My reading of the literature is that ADHD is heterogeneous in terms of neuropsychological profiles, with executive dysfunction being one important component but not a universal or defining feature of the disorder.

Not all individuals with ADHD show the same pattern or degree of impairment. Some even show no measurable cognitive deficits on standard tests (what’s going on there!). Complex attention tasks (sustained attention, vigilance) and working memory show the most reliable group differences. Traditional executive function tests (set-shifting, planning, inhibition) show inconsistent group differences across studies. Neuropsychological deficits in ADHD overlap substantially with other psychiatric conditions.

This is why clinical consensus is that neuropsychological assessment is neither necessary nor sufficient for ADHD diagnosis, and the “gold standard” for diagnosis remains a clinical assessment based on formal diagnostic criteria rather than neuropsychological testing.

The Anxious Adult with Attention Deficit

It is common for psychiatric clinicians these days to encounter adults who show a clinical picture of generalized anxiety and elevated neuroticism along with focus and attentional difficulties that resemble ADHD. Most of them were never diagnosed with ADHD as children, and often, the retrospective reports of childhood attentional problems aren’t that compelling either. And yet, many of them are genuinely impaired from focus difficulties, the focus difficulties persist despite adequate anxiety and mood treatment, and appear to benefit from stimulant medications.

This is related to what some folks call “anxious ADHD,” a hypothesized subset of individuals with a form of ADHD where anxiety is the primary subjective experience because executive dysfunction creates chronic stress and a perceived inability to cope.

The anxious adults with attention deficit who improve on a stimulant may genuinely have a profile of neuropsychological deficits with childhood onset but they could also just have attentional symptoms that respond to nonspecific motivational and arousal effects regardless of neurodevelopmental history. Stimulants improve alertness, motivation, and engagement in most people regardless of ADHD (although objective improvements on neuropsychological testing seem to be restricted to ADHD folks; most of the time, we are not testing that in the clinic, we are relying on perceived improvement). So a positive response to stimulants doesn’t confirm “ADHD,” but genuine clinical benefit from stimulants also cannot be dismissed just because the problem didn’t originate in childhood.

A situation like this represents several possibilities:

Our current diagnostic criteria poorly capture the genuine diversity of ADHD presentations.

There are transdiagnostic attentional deficit syndromes with or without neurodevelopmental onset.

Neurotypical people, or neurodevelopmentally intact individuals, can genuinely experience impairment from increased attentional demands that respond favorably to stimulants, and right now we don’t have a way of talking about them diagnostically.

Anxiety, mood, or memory symptoms are being misrepresented, misinterpreted, or misdiagnosed as primarily attentional symptoms.

I have suspected each of these possibilities at one time or another in different patients.

The Adult ADHD Perplexity

In the famous Moffitt et al. (2015) Dunedin study, most adults with ADHD at age 38 did not have diagnosed childhood ADHD. Adult-onset group showed significant functional impairment, but adult-onset group did not have neuropsychological deficits on testing.

In words of the authors,

“As expected, childhood ADHD had a prevalence of 6% (predominantly male) and was associated with childhood comorbid disorders, neurocognitive deficits, polygenic risk, and residual adult life impairment. Also as expected, adult ADHD had a prevalence of 3% (gender balanced) and was associated with adult substance dependence, adult life impairment, and treatment contact. Unexpectedly, the childhood ADHD and adult ADHD groups comprised virtually nonoverlapping sets; 90% of adult ADHD cases lacked a history of childhood ADHD. Also unexpectedly, the adult ADHD group did not show tested neuropsychological deficits in childhood or adulthood, nor did they show polygenic risk for childhood ADHD.”

Similar pattern has been found in other studies. Majority of ADHD adults do not have childhood diagnoses but they show comparable impairment to ADHD adults with childhood diagnosis.

Critics of the idea that adult ADHD can genuinely have an onset in adult tend to argue that “late-onset” cases may represent childhood subthreshold ADHD that progresses to full syndrome subsequently, many individuals in the late-onset group do show some ADHD symptoms in childhood, and that higher IQ and supportive environments can mask symptoms in childhood, with decompensation occurring with demands of adulthood.

So the psychiatric community is divided along 3 camps, so to speak.

Childhood-onset ADHD and adult-onset ADHD are distinct syndromes, and only the former is neurodevelopmental in origin.

Most late-onset ADHD cases are instances of delayed expression of subthreshold childhood ADHD or delayed recognition of childhood-onset ADHD.

Age of onset criterion is unreliable and of uncertain clinical significance anyway. Clinicians should focus on current symptoms and impairment. Treat what’s clinically present.

DSM doesn’t currently recognize adult-onset ADHD, so clinicians who want to diagnose by the book either have to ignore the attentional impairment and continue treating anxiety and mood, or they have to look really hard for and overinterpret evidence in support of childhood ADHD.

I am partial to the third view, the pragmatic clinician camp, while acknowledging that the true relationship between adulthood ADHD and childhood ADHD is a matter for science to clarify. Adults who show ADHD symptoms without clear-cut childhood onset are still impaired, and stand to benefit from treatment. I do not think we should let patients suffer while our formal classification systems play catch-up with clinical realities.

The Venn diagram of ADHD and stimulant use is not a circle

Stimulant medications have therapeutic effects that go beyond ADHD. Some of these therapeutic uses are already formally recognized. Stimulant medications are used in sleep disorders such as narcolepsy. They can be useful in geriatric depression as well as depression with residual fatigue/anergia. They can be useful in various neuropsychiatric disorders with prominent apathy, fatigue, or focus difficulties.

There are situations where clinical use of stimulants is clearly inappropriate, but neurodevelopmentally intact people experiencing genuine impairment from excessive and inescapable attentional demands also constitute a clinical grey area that the profession seems hesitant to talk about. It brings its own ethical challenges… what to do about situations where people are overwhelmed by the requirements of work in the post-Fordist era? What to do about “Mother’s Little Helper” type scenarios? What about people trying to survive in time-pressured work environments? Or those trying to use stimulants to cope with chronic sleep deprivation? Or those so depleted by anxiety and stress that they have no motivation left for unrewarding tasks on which their survival depends? And yet, amidst all these clinical dilemmas, we also show a certain hypocrisy: we do not withhold SSRIs from people who experience impairment from increased emotional demands. The diagnostic criteria for depression are oblivious to context.

My allegiance is not to diagnostic manuals; it is to my patients. I am not doing my job well if I refuse to recognize distress and impairment that can be addressed via appropriate clinical interventions. But what I do not want to do is provide that help under false pretenses. I don’t want to say someone has a neurodevelopmental disorder when they don’t so that they can access a medication that they can benefit from.

The Venn diagram of ADHD and stimulant therapeutic effects is two overlapping circles. And yet there is tremendous pressure in clinical practice to treat those circles as coinciding.

The clinical use of stimulants beyond ADHD (and a handful of other diagnoses) is an uncharted territory from the vantage of “evidence-based medicine.” There is little we can say with confidence or certainty. And yet, countless clinicians and patients have been operating in this territory for a long time while having to pretend they are still in the charted ADHD territory. Because of our ridiculous moralism around stimulant medications and diagnostic conservatism about attentional problems, we have become unable and unwilling to recognize clinically significant distress and impairment in all its shapes and forms.

See also:

This is such a fascinating discussion. One thing that I wonder about as a clinical counselor is about *core shame* as a variable. Those with ADHD diagnosis seem to have more core shame (“Something is wrong with me”) and I wonder if this is tied to genetic brain sensitivity (ie, a brain that is predisposed to emotional sensitivity?) In the ADHD self help literature for women, healing the shame underneath the dysfunction seems to be a big emphasis, and in my experience, it really seems to help decrease the severity of the symptoms. Is shame a “stickier” experience for a genetically sensitive brain? I guess I'm wondering: do stimulants present us with a drug that helps alleviate shame through increased feelings of self-efficacy and the feeling that “now my brain is like normal people’s brains?” If a child in the woods has ADHD but never has an environment that creates any friction for shame to take root, would the symptoms even express themselves at all? In other words, how much of this is environmental and as a result of a brain that genetically tilts towards sensitivity/shame? How many of these individuals have internalized the belief “Something is wrong with me” and the stimulants give them relief through counter evidence (“I can do things in the manner in which I perceive that normal people can?”)?

Yet another thoughtful and important piece, and I especially appreciate the emphasis on the Venn diagram of ADHD and stimulant benefit being overlapping but non-identical. I also love how you effectively communicate both the framing of ADHD as a distributed, heterogeneous, and idiographic process, and the idea that “attention” itself is a highly transdiagnostic and multifaceted construct rather than a unitary faculty.

I wonder, though, if there is a third clinical dilemma that sits alongside the one you describe. You frame the tension as being between clinicians who see genuine distress but feel constrained by rigid diagnostic boundaries, versus a more pragmatic stance that prioritizes current impairment and benefit over strict adherence to developmental criteria. That dichotomy may well reflect what you see in psychiatry.

From the neuropsychology side, what I encounter much more often is a slightly different situation: many of us see a lot of individuals who are genuinely distressed and sincerely believe they have ADHD, but for whom there is strong objective evidence that they do not currently have clinically significant, functionally impairing attentional or executive deficits. Not only is there often weak evidence for childhood ADHD, but present-day functioning is frequently average to well above average across cognitive testing, occupational functioning, health behaviors, and life outcomes, with little corroboration from objective collateral sources.

These individuals are often highly conscientious, high-achieving, and operating in very demanding environments. Their distress is real -- they feel exhaustion, shame, anxiety, a sense of underperforming relative to peers -- but the clinical picture looks less like a neuropsychological disorder and more like a collision between human limits and extreme expectations (plus stress, sleep, cannabis, social media, modern work demands, etc.).

In these cases, the dilemma is not whether to withhold help out of rigid diagnostic moralism. It’s that diagnosing and prescribing are not neutral acts. Telling someone who is objectively within the normal range of human functioning, “Yes, you have a medical disorder that explains your struggles, and you require ongoing professional intervention” (or even pragmatically just the last part of that statement) carries a lot of implicit messages. Messages about where the problem resides, what kinds of limits are acceptable, what counts as failure, and what sort of relationships (with yourself, with your communities, with your purpose, with society) is encouraged.

I sometimes think the analogy is closer to cosmetic surgery vs. surgical repair for cleft palate. In both cases, there is genuine distress and genuine potential benefit, but the two situations are different, and come with very different ethical, cultural, and professional implications. There may well be a place for something like “cosmetic psychiatry,” where people pursue enhancements or supports they do not medically need but may want and value. What makes me uneasy is when that territory gets collapsed into medical diagnosis (or 'pragmatic diagnosis', if I may use that as shorthand for your pragmatic self-reported distress + potential benefit stance), and when clinicians who resist that move are framed as insufficiently empathic or nuanced.

So, I think I agree with almost everything you’re saying about the science and about the limits of current diagnostic categories. I just want to add that there is also a responsibility on the clinician’s side to hold the line between recognizing distress and reifying it as disorder, especially given the downstream effects on patients, professional norms, and society more broadly. (I'm resisting the temptation here to expand on all of these effects, as you've covered many of them on this very Substack, so I know they're in the background of this post even though the medical diagnosis vs pragmatic stance is being foregrounded).

I just want to gently offer that colleagues who push back against making a medical OR pragmatic diagnosis probably are not looking to deny suffering. They're finding the best answer they can to the question of what kind of story about that suffering we're ethically justified in telling.