“Drug-centered model” of psychopharmacology doesn’t mean what you think it means

Moncrieff’s disease-centered vs drug-centered distinction makes quite specific and peculiar commitments

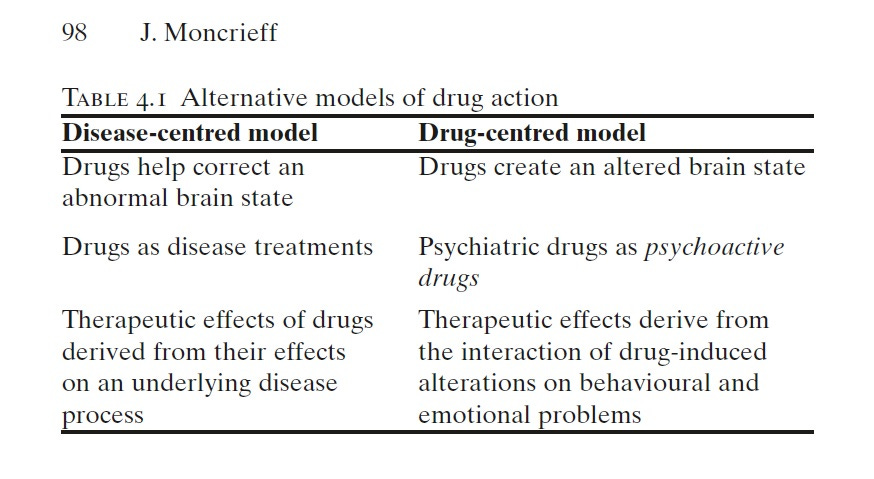

Joanna Moncrieff's distinction between “disease-centered” and “drug-centered” models of psychopharmacology is quite influential in critical psychiatry circles, even as it remains ignored by the mainstream psychiatric community. Many folks are quite drawn to it when they first encounter it, and indeed, in the beginning, I myself found it of some value. However, it is also evident to me that many, maybe even most, people who tend to invoke and reference the drug-centered approach fundamentally misunderstand what the model asserts and what theoretical commitments accompany it.

Most people see the drug-centered model as making the negative assertion that psychiatric medications do not work by correcting dysfunctions, and they often talk as if the drug-centered model makes no commitments regarding the mechanisms by which psychiatric medications do actually work. But the drug-centered model, in fact, makes quite specific and peculiar commitments.

The easiest way to illustrate what the drug-centered model is saying is by contrasting it with another common distinction in medicine: disease-modifying vs symptomatic treatment. A disease-modifying treatment targets the etiological or pathophysiological mechanisms of a medical condition to cure it, or to delay or slow down its progression. Symptomatic treatments, on the other hand, act on the symptoms (such as cough, fever, pain, swelling…) without modifying the core pathophysiology or altering the long-term course or progression. This distinction is not without its problems, especially in psychiatry and other areas of medicine where the conceptualization between symptom and disease/disorder remains murky, and we may consider it more of a spectrum than a dichotomy, but it’s a distinction that almost everyone in medicine intuitively understands.

If the drug-centered model were simply asserting that the medication is not correcting a dysfunction, that would imply a general similarity with the notion of symptomatic treatment, that psychiatric medications are symptomatic treatments but not disease-modifying.1 But in fact, according to the drug-centered model, most symptomatic treatments in general medicine actually fall under the category of “disease-centered.” This is because of two peculiar features of the drug-centered model:

i) The disease-centered model isn’t simply about acting on dysfunctions but also encompasses the physiological mechanisms that underlie symptoms, such that any action on the physiological mechanisms that underlie symptoms is considered disease-centered.

ii) Psychoactive effects are distinguished from and treated differently from physiological effects of medications

Consider analgesics, which are a fairly standard example of symptomatic treatment. Moncrieff believes that analgesics such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen work in a “disease-centered” manner by acting on the physiological processes that produce pain. Antidepressants, in contrast, Moncrieff believes, do not act on the physiological processes that produce the symptoms of depression. So how do they act instead? Moncrieff believes that taking antidepressants produces emotional blunting that numbs both positive and negative emotions, leading to a reduction in the intensity of feelings of depression. This emotional blunting does not act on mechanisms of depressed mood, but rather is a superimposed psychic state that suppresses the experience of depression.

For example, recently, in the context of the serotonin hypothesis, Moncrieff et al. write:

“[Although we agree that] medical treatments do not always reverse the primary cause of the pathology they are used to treat, most modern medical treatments in physical healthcare, including those cited, do act on biological processes associated with the mechanisms that produce the symptoms or signs in question (e.g. blood volume for diuretics in hypertension) even if they do not act on the primary mechanisms (which are sometimes unknown) in what we have called elsewhere a ‘disease-centred’ model of drug action. This is different from the way psychoactive compounds interact with people’s thoughts and feelings as suggested by the ‘drug-centred’ model. An example of the latter in physical medicine is the way the intoxicating effects of alcohol were used to distract people from pain before more targeted analgesics were available.”

In case anyone is surprised that the drug-centered model takes this view, this isn’t a new position taken by Moncrieff. She has maintained this since the very beginning. In a 2013 article, she notes: “The vast majority of medical drugs target the underlying mechanisms that produce symptoms or disorders. Anti-asthma drugs, for example, work by dilating constricted airways, anticancer drugs by targeting mechanisms of cell proliferation, and pain killers act on the physiological pathways that produce pain.”

And in a 2018 article:

“The disease-centred model has been imported from general medicine, where most modern drugs are correctly understood in this way. Although most medical treatments do not reverse the original disease process, they act on the physiological processes that produce symptoms. Thus, β agonists help reverse airways obstruction in asthma and chemotherapeutic agents counteract the abnormal cell division that occurs in cancer. Analgaesics such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs also work in a disease-centred manner by acting on the physiological processes that produce pain.”

So what does Moncrieff’s drug-centered model say about how psychiatric medications work?

“… psychiatric drugs are psychoactive substances like alcohol and opiates and that modify normal feelings and behavior, producing an altered state of consciousness. According to this model, the altered, drug-induced state is understood to suppress or mask the symptoms of mental distress or disturbance.” (Moncrieff, 2013)

“The drug-centred model suggests that it is these psychoactive properties that explain the changes seen when drugs are given to people with psychiatric problems. Drugs like benzodiazepines and alcohol, for example, reduce arousal and induce a usually pleasant state of calmness and relaxation. This state may be experienced as a relief for someone who is intensely anxious or agitated; but taking a drug like this does not return the individual to ‘normal’, or to their pre-symptom state. It is simply that the drug-induced state may be preferable to intense anxiety.

There are few examples of drugs working in a drug-centred way in modern medicine, but historically the psychoactive effects of alcohol were an important part of its analgaesic properties. Opiates also work partly through a drug-centred mechanism. Although they reduce pain directly by inhibiting the conduction of pain stimuli (a disease-centred action), they are psychoactive drugs that induce an artificial state of emotional indifference and detachment. People who have taken opiates for pain often say that they still have some pain, but do not care about it anymore.” (Moncrieff, 2018)

Moncrieff’s drug-centered model posits a particular kind of interaction between certain psychoactive effects (sedation, cognitive slowing, euphoria, activation, emotional blunting, etc.) and psychiatric symptoms, such that the symptoms are masked, or suppressed, or the individual is distracted from them, or does not care about them anymore, and the interaction doesn’t involve any action on the physiological processes that produce symptoms.

This is what it actually means to accept the drug-centered model.

Moncrieff’s drug-centered model posits a particular kind of interaction between certain psychoactive effects (sedation, cognitive slowing, euphoria, activation, emotional blunting, etc.) and psychiatric symptoms, such that the symptoms are masked, or suppressed, or the individual is distracted from them, or does not care about them anymore, and the interaction doesn’t involve any action on the physiological processes that produce symptoms.

Moncrieff conflates both disease-modifying and symptomatic treatments into the category of “disease-centered model” and she asserts a crucial distinction between psychoactive effects improving symptoms in a manner that doesn’t involve acting on the physiological processes that produce symptoms.

What are the problems with this?

1. Most people don’t realize that disease-modifying and symptomatic treatments are being conflated together.2

2. It is obvious that an interaction between psychoactive effects and psychiatric symptoms at the psychological level must also involve an interaction of some sort between psychoactive effects and psychiatric symptoms at the physiological level.

3. Accepting the drug-centered model imposes a severe restriction on what sorts of hypotheses we can consider to explain the mechanisms of psychiatric medications. The only kosher mechanisms are those that invoke effects such as sedation, cognitive slowing, and emotional blunting, because the possibility of psychiatric medications having any direct effects on mechanisms and processes related to symptoms is dismissed as “disease centered.” This hypothesis may be applicable to some patients and some situations, but considering all the hypotheses we have at our disposal and that have some degree of scientific support (neurotransmitter systems, neuroplasticity, neurogenesis, endocrine pathways, inflammatory pathways, neurocognitive mechanisms such as prediction errors, etc.), we have good reasons to believe that the general applicability of this hypothesis is quite limited.

4. The difference between acting on a psychological mechanism that produces symptoms and a psychoactive effect that suppresses symptoms is a conceptually important one, but the drug-centered account doesn’t seem to have the conceptual resources to articulate it.

5. In addition to mechanisms that produce symptoms, we can also talk about mechanisms that sustain symptoms (once they are generated) and mechanisms that influence symptoms (in terms of severity or quality). The more such mechanisms exist and the more they are likely targets of psychiatric medications, the less support there is for the idea that psychotropics do not act on symptom mechanisms.

6. It allows for a sort of motte-and-bailey argument where “the medication doesn’t correct a dysfunction” (the motte) is taken to assume “the medication works by blunting/numbing/masking your symptoms” (the bailey), and when the bailey is challenged, the person simply retreats to the motte without changing their views and while continuing to assert the bailey any opportunity they get.

It allows for a sort of motte-and-bailey argument where “the medication doesn’t correct a dysfunction” (the motte) is taken to assume “the medication works by blunting/numbing/masking your symptoms” (the bailey), and when the bailey is challenged, the person simply retreats to the motte without changing their views and while continuing to assert the bailey any opportunity they get.

7. The idea that psychiatric medications simply numb or suppress painful emotions – essentially no different from consuming alcohol – can veer dangerously close to a moral stance towards psychopharmacology, even if this is unintended. Such danger is particularly acute when it is believed that “what we characterize as mental illness, therefore, refers not to an illness or disease, but to patterns of unusual but still essentially self-directed behavior. These patterns can be understood as aspects of character…” as Moncrieff does.

8. Medications often work in ways that are independent of the existence of any “disease” process, but that is as true of general medicine as it is of psychiatry. We still have to figure out what effects medications have (which span across neurobiology, cognition, phenomenology, etc.) and how these effects modify and interact with the mechanisms and processes involved in the generation or maintenance of the particular clinical state we are trying to address. These interactions are complex and only inadequately classified as either “disease centered” or “drug centered.” As is the case with other Szaszian binaries, the illusion only works if you accept the binary at face value. In order to problematize this binary, consider the following approaches, in addition to the disease-modifying vs symptomatic distinction we have already discussed, that do not come with the same restrictive commitments:

“Effects-centered psychopharmacology”: an approach that encourages consideration of the full-range of effects produced by psychotropics and makes no commitments regarding the relationship between the mechanisms of action and the symptoms being targeted.

“Phenomenological psychopharmacology”: an approach that encourages examination of phenomenological changes that accompany psychotropic use.

“Outcome-centered psychopharmacology”: an approach that encourages us to look at how psychotropics modify various clinical outcomes of interest to us.

“Iatrogenic psychopharmacology”: an approach that emphasizes attention to iatrogenic harm in all its manifestations, even in instances where medications produce therapeutic effects by acting on disease mechanisms.

Given its problematic theoretical commitments, there was never any good reason to accept the “disease-centered” vs “drug-centered” binary. Give it up, for this way lies only confusion and error.

Given its problematic theoretical commitments, there was never any good reason to accept the “disease-centered” vs “drug-centered” binary. Give it up, for this way lies only confusion and error.

Regarding my own thinking around psychopharmacology, I will refer you to

1) My article “Psychopharmacology and Explanatory Pluralism” (2022) in JAMA Psychiatry that makes a case for incorporating higher levels of explanation in clinical psychopharmacology and argues for the need to embrace interactions at multiple levels via multiple pathways with top-down and bottom-up causal influences.

2) My article “A Psychopharmacology Fit for Mad Liberation?” for Asylum Magazine that asks how psychopharmacology can serve the needs of the mad, distressed, and psychosocially disabled.

See also my other critiques of binary thinking in Moncrieff’s work:

3) The false binary between biology and behavior (2020) in Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology

4) Beyond problematic binaries in mental healthcare (2022) in Psychological Medicine

The view that psychiatric medications are, for the most part, symptomatic and not disease-modifying has been prominently advocated within psychiatry by S. Nassir Ghami (2022).

This is evident, rather hilariously, from the twitter responses to Nassir Ghaemi’s article Symptomatic versus disease-modifying effects of psychiatric drugs. Criticals argued on its publication that Ghaemi had copied Moncrieff’s distinction, revealing their own ignorance in the process.

This is a very helpful piece Awais, and I think it all on point. ... On "4. The difference between acting on a psychological mechanism that produces symptoms and a psychoactive effect that suppresses symptoms is a conceptually important one, but the drug-centered account doesn’t seem to have the conceptual resources to articulate it." I'm wondering whether this is always so clear. Is it that I've not noticed my tinnitus today, or that it's not been there? Is it that my low mood is the same but I don't care about it so much, or is that very idea of a separation between mood and caring about mood itself a nonsense? Does the lucid dreamer really wake up in their dream, or do they dream they wake up in their dream? etc etc. We can sometimes find ways to make such suggestions cogent, but I'm not sure we always can, nor that we should always want to.