Making Sense of the Literature on Antipsychotics and Long-Term Functioning

Taking natural history and personalization seriously

At face value, the literature on the relationship between antipsychotic use and long-term (> 2 years) individual and social functioning gives the impression that antipsychotic use worsens outcomes, but the association is severely confounded by natural history and other individual characteristics. This post is an attempt to make sense of the literature and consider clinical implications.

There is a fair bit of clinical literature review involved; if that’s not something of interest to you, and you are more interested in the conclusions and the clinical implications, you can jump to the section ‘Taking into account natural history, functioning, and effects of antipsychotics.’

The first thing we have to take into account is the long-term course of psychotic disorders and rates of recovery and sustained recovery.

A recent epidemiological study by Tramazzo et al. from Suffolk County, USA, looked at trajectories of illness course for 25 years since first admission for psychosis.

For people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, about one in four were in recovery or remission during the first four years. However, by the 25-year mark, these rates dropped to 13% and 5%, respectively. In contrast, those with other psychotic disorders (not schizophrenia spectrum) had remission and recovery rates above 50% for the first 20 years, which only fell below this level at the 25-year follow-up. The study also found a high mortality rate of 20%. Remission is the absence of symptoms, while recovery includes the possibility of moderate symptoms but with good overall functioning. Recovery rates were higher than remission rates at almost every follow-up point, suggesting that many individuals manage to function well despite having some symptoms.

While the cross-sectional recovery rates in schizophrenia spectrum disorders are somewhat encouraging (16% at 10 years and 22% at 20 years), sustained recovery and remission rates are sobering, to say the least. As authors describe, the most common trajectory for individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders was no remission and no recovery. “Individuals with other psychotic disorders were more likely to experience stable remission (15.1%) and stable recovery (21.1%), outcomes that were rare among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (0% and 0.6%, respectively).”

Similar to the Suffolk study, in the OPUS cohort (Denmark), 14% met the criteria for symptomatic and psychosocial recovery at 10 years. The cross-sectional rates of recovery here are consistent with a large and rigorous 2013 meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Authors defined recovery as improvements in both clinical and social domains, with improvements persisting for at least 2 years. Based on data from 50 studies, they reported that the median (25%–75% quantiles) recovery rate was 13.5% (8.1%–20.0%).

Other studies have reported higher recovery rates as well. Usually first-episode psychosis cohorts with lower proportion of schizophrenia patients find higher rates of recovery. Population-representative samples find poorer outcomes than some selected cohorts. The longer the duration over which sustained improvement is examined, the lower the rates.

Taylor and Jauhar (2019) reviewed relapse and recovery data in psychosis over the last 100+ years. The pattern generally holds, even in the era prior to antipsychotics. They note:

“Kraepelin’s own series of hospital-based cases revealed spontaneous complete recovery in approximately 15% of his dementia praecox patients, although data on relapse in this series appears lacking.”

“In a careful review of the literature, McKenna identified two other methodologically rigorous studies from the preantipsychotic era: Langfeld’s study of 100 patients followed up for 7–10 years, and a similar study of 160 patients followed up for 6–8 years. Both found a similar proportion of people, approximately 20%, were in the best two outcome groups, with most experiencing complete recovery.”

Taylor and Jauhar conclude that about 20% of patients with first episode psychosis fully recover and never experience relapse subsequently, even in the absence of antipsychotic medication.

In the Chicago Follow-up study by Harrow, et al., which is generally described in the literature as a small selected cohort (N=70 of schizophrenia patients), predominantly affluent, and drawn mainly from those admitted to a psychoanalytic-based hospital, 20% of people with schizophrenia did not experience subsequent psychosis during a 20-year follow-up period after initial hospitalization(s).

In the AESOP study (UK), a 10-year follow-up study of 557 individuals with a first episode of psychosis from South East London and Nottingham, 46% had been symptom free for at least 2 years. Among those with non-affective psychosis, this figure was 40%. (This is more than double the rate in the Suffolk study above.)

What’s more interesting to note in AESOP is the differentiation between symptom trajectories:

Very few people with psychotic disorders have a continuous course and a good outcome (2%). Vast majority of people with good outcome have an intermittent course. Not obvious in this figure (subsumed under undulating course, I think) are those who only have one episode of psychosis and then experience long-term remission.

We can roughly characterize the clinical trajectories in psychotic disorders as follows:

Long-term remission of symptoms after initial episode of psychosis

Long-term remission of symptoms after two or more episode of psychosis

Recurrent episodes of psychosis

Chronic, persistent psychosis

Symptoms can range from mild to severe for any of them, and functioning similarly can range from poor to good. We can expect that those with long-term remission will be disproportionately represented in the high functioning group. When we have a cross-section of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in symptom remission in observational studies, the cross-section would consist mostly of a mix of people in long-term remission and people with recurrent psychosis who are in between episodes in a psychosis-free interval. The exact proportion of these groups would vary from sample to sample, and from time to time.

When we have a cross-section of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in symptom remission in observational studies, the cross-section would consist mostly of a mix of people in long-term remission and people with recurrent psychosis who are in between episodes in a psychosis-free interval.

As far as I am aware, there is little to no evidence that antipsychotics change the long-term course of schizophrenia. Antipsychotics reduce psychotic symptoms, they reduce the risk of relapse, they have modest benefits on functioning (at least in the short term and up to about a year), and they probably reduce mortality, but they don’t change the long-term trajectory. This is important because any long-term, observational study of antipsychotic use risks becoming a naturalistic study of the long-term course of psychotic disorders.

Any long-term examination of antipsychotics in psychotic disorders must contend with the fact that the sample will display these different trajectories over time, and at present there is no clinical tool or measure that predicts these trajectories with accuracy. The people in the long-term recovery trajectory will naturally be the ones who will find it easy to discontinue antipsychotics and stay well.

There is little to no evidence that antipsychotics change the long-term course of schizophrenia… any long-term, observational study of antipsychotic use risks becoming a naturalistic study of the long-term course of psychotic disorders.

Antipsychotics work reasonably well in the short-term treatment of psychosis, for symptom control but also quality of life and functioning

Leucht et al (2017). Sixty Years of Placebo-Controlled Antipsychotic Drug Trials in Acute Schizophrenia

“The analysis included 167 double-blind randomized controlled trials with 28,102 mainly chronic participants. The standardized mean difference (SMD) for overall efficacy was 0.47 (95% credible interval 0.42, 0.51), but accounting for small-trial effects and publication bias reduced the SMD to 0.38. At least a “minimal” response occurred in 51% of the antipsychotic group versus 30% in the placebo group, and 23% versus 14% had a “good” response. Positive symptoms (SMD 0.45) improved more than negative symptoms (SMD 0.35) and depression (SMD 0.27). Quality of life (SMD 0.35) and functioning (SMD 0.34) improved even in the short term.”

Antipsychotics work reasonably well in RCTs of maintenance treatment of schizophrenia up to 1 year, for relapse prevention but also quality of life and functioning

Ceraso et al (2022). Maintenance Treatment With Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia: A Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

“The updated review included 75 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published from 1959 to 2017, involving 9145 participants. Although some potential sources of bias limited the overall quality, the efficacy of antipsychotic drugs for maintenance treatment in schizophrenia was clear and robust to a series of sensitivity analyses. Antipsychotic drugs were more effective than placebo in preventing relapse at 1 year (drug 24% versus placebo 61%, 30 RCTs, n = 4249, RR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.32 to 0.45) and in reducing hospitalization (drug 7% versus placebo 18%, 21 RCTs, n = 3558, RR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.32 to 0.57). Quality of life appeared to be better in drug‐treated participants (7 RCTs, n = 1573, SMD = −0.32, 95% CI = −0.57 to −0.07); the same for social functioning (15 RCTs, n = 3588, SMD = −0.43, 95% CI = −0.53 to −0.34). Although based on data from fewer studies, maintenance treatment apparently increased the possibility to achieve remission of symptoms (drug 53%, placebo 31%; 7 RCTs, 867 participants; RR = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.20 to 2.48) and to sustain it over 6 months (drug 36%, placebo 26%; 8 RCTs, 1807 participants; RR = 1.67, 95% CI = 1.28 to 2.19).”

Antipsychotics, however, have significant adverse effects.

Sedation, akathisia, anticholinergic effects, and weight gain are commonly experienced with many different antipsychotics during acute treatment (Huhn, et al. 2019).

From the Cochrane review (2022) of maintenance treatment:

“Antipsychotic drugs (as a group and irrespective of duration) were associated with more participants experiencing movement disorders (e.g. at least one movement disorder: drug 14% versus placebo 8%), sedation (drug 8% versus placebo 5%), and weight gain (drug 9% versus placebo 6%).”

The neuroleptic effect of chlorpromazine was initially described at the time of discovery as “sedation without narcosis.” In addition to sedative effects such as drowsiness and somnolence, effects such as psychological indifference, apathy, psychological numbing, are also commonly experienced.

These adverse effects are important to the question of long-term functioning, because, as Wunderink et al. (2013) put it:

“Antipsychotic postsynaptic blockade of the dopamine signaling system, particularly of the mesocortical and mesolimbic tracts, not only might prevent and redress psychotic derangements but also might compromise important mental functions, such as alertness, curiosity, drive, and activity levels, and aspects of executive functional capacity to some extent.”

We should expect these problems to be worse with high doses, higher than standard doses, and with polypharmacy.

A recent meta-analysis of 35 studies by Schlier et al (2023) investigated how the effect of antipsychotic maintenance treatment vs. discontinuation/dose-reduction on social functioning and subjective quality of life in patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders changes over the years.

They found that middle-term (2–5 years; 7 studies) and long-term follow-ups (>5 years; 2 studies) significantly favored discontinuation, but due to methodological problems, risk of bias, and very low quality of evidence, any conclusions are premature.

“Whilst short-term studies (<2 years) favoured maintenance treatment, antipsychotic discontinuers showed increased social functioning in middle- and long-term follow-ups. However, caution is warranted as the number of studies with middle-term (k = 7) and long-term follow-ups (k = 2) was critically low. In addition, most of the middle- and all of long-term studies had a non-randomised study design and a high risk of bias. Typical reasons for this are the inherent possibilities of self-selection bias in naturalistic study designs. For example, less severely impaired participants might opt for or persist with discontinuation more frequently, show more favourable outcomes at baseline than participants in RCTs, which could account for the association of discontinuation and favourable outcomes in these studies.”

Randomized studies are higher quality and favor maintenance treatment but they are short-term (< 2 years), while longer studies are non-randomized and favor discontinuation.

Let’s take a look at three studies from the meta-analysis to get a sense of the issues involved. I have picked one middle-term study (Wunderink et al, probably the most famous study from this meta-analysis), and the two long-term follow-ups included in the analysis (studies by Harrow et al and Wils et al).

Wunderink et al. Mesifos trial. 7-year outcomes

In the Mesifos trial, researchers investigated the outcomes of treatment-naïve patients with first-episode psychosis (n = 128). At baseline, 45% of the participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia (likely an underestimate). After achieving six months of remission from positive psychotic symptoms, these patients were randomly assigned to either a dose reduction and discontinuation (DR) strategy or a maintenance treatment (MT) strategy.

Relapse rate in the DR group was found to be twice as high compared to the MT group: 43% versus 21%. Additionally, patients in the DR group did not show improved functioning on average.

Following the initial two-year randomization period, patient care was managed at the discretion of their psychiatric clinicians. Five years later, a follow-up study was conducted looking at 7-year outcomes looking at 103 patients from the original cohort.

The seven-year follow-up revealed significant differences in outcomes. Patients originally assigned to the DR strategy had a higher rate of recovery (symptom remission + functional remission) compared to those in the MT group: 40.4% versus 17.6%. There were no apparent confounding factors influencing these results. Symptom remission rates (independent of functioning) were similar between the two groups, at 69.2% for the DR group and 66.7% for the MT group. Notably, relapse rates in the DR group eventually equaled those in the MT group by around the third year of follow-up, such over the 7-year period, the two groups had an overall equal number of relapses.

During the 2-year randomized phase, the mean daily dosages of haloperidol equivalents were 2.1 mg for the DR group and 2.9 mg for the MT group (the average difference doesn’t seem that high to me but is apparently enough to produce a higher rate of relapse). The mean antipsychotic dose during the last two years of follow-up remained significantly different: 2.2 mg daily for the DR group versus 3.6 mg daily for the MT group.

During the two-year randomization phase, 21.5% of patients in the DR group successfully discontinued medication without relapse, 24.6% discontinued but had to restart due to relapse, and the rest reduced their dose without discontinuing. A few patients in the MT group also discontinued antipsychotics on their own.

At the seven-year follow-up, 21% from the DR group and 12% from the MT group had discontinued antipsychotics. Additionally, the same number of patients were using less than 1 mg of haloperidol equivalents daily during the last two years of follow-up. Thus, a total of 34 patients (33.0%) were on no or very low dose antipsychotic medication at the 7-year follow-up: 22 (42.3%) in the DR group and 12 (23.5%) in the MT group.

Critics have generally focused on the fact that the last 5 years are naturalistic and non-randomized, and therefore it is difficult to draw strong conclusions. Leucht and Davis (2017), for example, say: “The major limitation was that after the initial 2 years the study was no longer randomised, meaning that patients did not follow the treatment that they had been initially assigned to any longer. Much can have happened in 5 years. This makes it impossible to derive a causal relationship between the initial attempt to withdraw antipsychotics and better functional outcome at 7 years.”

Wunderink’s (2019) response to such criticisms is: “Though the critics do not deem a causal relationship between the early DR strategy and better long-term functional outcome likely, there are no convincing arguments to dispute these results. But obviously robust evidence requires replication in other trials.”

There are 3 ways to look at the Mesifos trial.

a) Dose reduction/discontinuation during early years of treatment produces functional benefit years down the road.

Strictly speaking, the Wunderink study is looking at the long-term functional effects of a dose reduction/discontinuation strategy only during the first 2 years of treatment of first-episode psychosis. In this scenario, what matters is what happened during the first 2 years of randomization, and what happened naturally during the subsequent 5 is of less consequence. In other words, there is a functional benefit of early antipsychotic dose reduction but it doesn’t become evident until years later.

b) It is impossible to establish a causal relationship between early dose reduction and better functional outcome at 7 years.

This is the view of critics such as Leucht and Davis, and probably the view of most psychiatrists. Here’s how I see this. It is true that “much can have happened in 5 years” but it is also true that there is no other obvious explanation for the functional discrepancy other than early dose-reduction/discontinuation. The only way to really demonstrate that such a relationship exists is robust replication. One study can be a fluke, but if we can repeatedly demonstrate that dose-reduction/discontinuation shows better functional outcomes years later, we’d have to take that seriously.

c) Dose reduction/discontinuation produces better functional outcomes years down the road, but in order to see this difference, the DR group must continue to take antipsychotics at a dose lower than the MT group.

I haven’t seen this possibility discussed much, but it seems relevant to me because the DR group still had a lower average antipsychotic dose during years 5-7 compared to the MT group: 2.2 mg Haloperidol-equivalent daily for the DR group versus 3.6 mg daily for the MT group. Again, the only way to demonstrate whether this is the case would be robust replications of the Mesifos trial, such that in some replications the two groups are on similar antipsychotic dose during the years 5-7 years and in some replications, the two groups continue to differ. That would tell us whether only early dose-reduction matters or whether persistent dose-reduction is needed for improved functional outcomes.

Wils et al. Danish OPUS cohort, 10-year outcomes

In a study by Wils et al. (2017), researchers followed 496 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders as part of the Danish OPUS Trial. Ten years later, 61% of the original participants attended a follow-up assessment. 30% of these patients had achieved remission of psychotic symptoms and were no longer using antipsychotic medication.

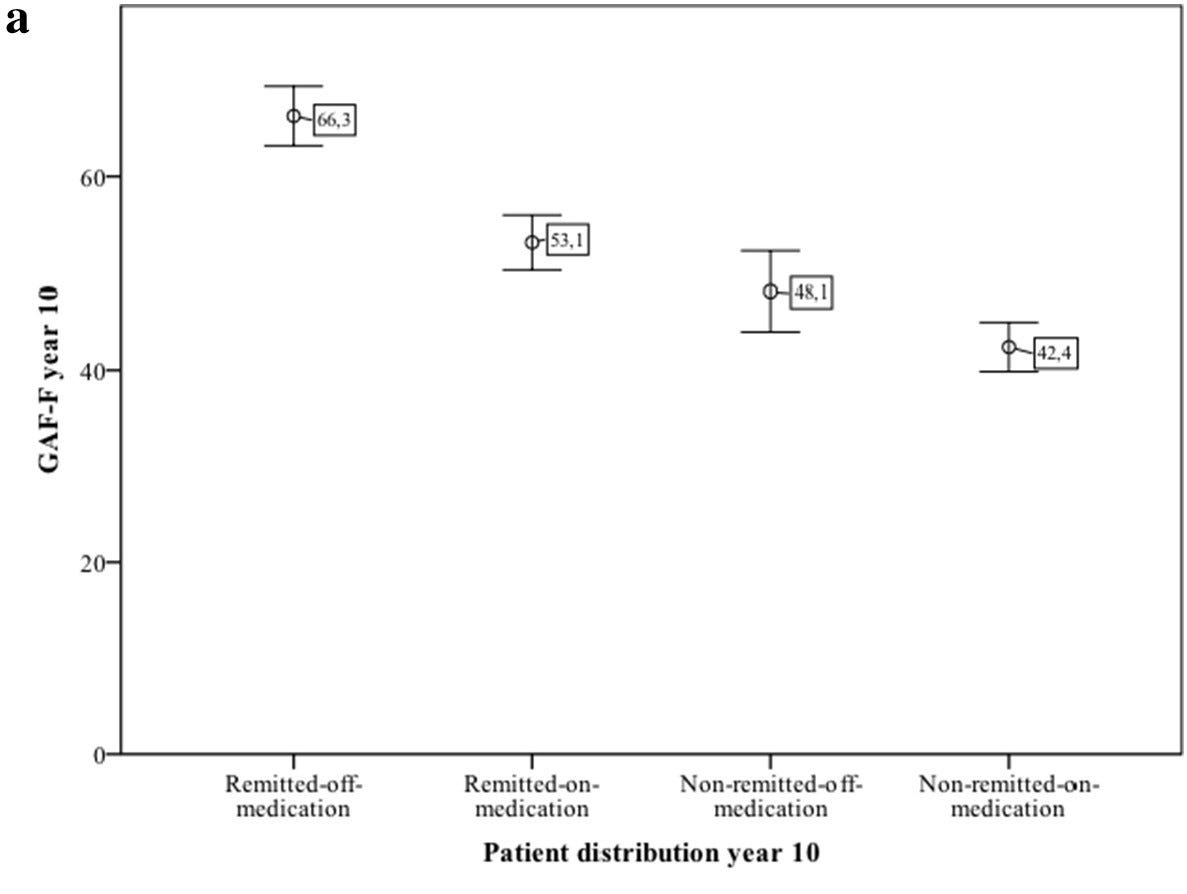

The study population at the 10-year follow-up was divided into four groups. The Remitted-off-medication and Remitted-on-medication groups each comprised 30% of the patients. The Non-remitted-on-medication group accounted for 31%, making it the largest group. The smallest group was the Non-remitted-off-medication group, which included 10% of the patients.

Remitted-off-medication group had the best functioning (measuring using GAF) among these groups, followed by remitted-on-medication, followed by non-remitted-off-medication, with non-remitted-on-medication having the worst functioning. That is, in both remitted and non-remitted groups, those not on antipsychotics had better functioning.

The study is cross-sectional, looking at year 10, and does not examine the causality between outcomes and medication status. It is therefore vulnerable to the natural history considerations outlined above. The authors are also careful not to make any causal assertions.

Those who successfully discontinue antipsychotics are in all likelihood systematically different from those who are unable to discontinue or unsuccessfully discontinue and then resume. They are likely to be either folks who are naturally on the long-term remission trajectory, or they are folks with chronic symptoms who have the psychological and social resources to manage symptoms without antipsychotic medications.

Those who successfully discontinue antipsychotics are are in all likelihood systematically different from those who are unable to discontinue or unsuccessfully discontinue and then resume. They are likely to be either folks who are naturally on the long-term remission trajectory, or they are folks with chronic symptoms who have the psychological and social resources to manage symptoms without antipsychotic medications.

Harrow et al. Chicago Follow-up study. 15- and 20-year outcomes.

The Chicago Follow-up Study was designed to naturally observe and track the progress of individuals with serious mental illnesses over time. This long-term study focused on understanding the course of the illness, outcomes, symptoms, effects of medication, and recovery. The participants, who mostly had schizophrenia and affective psychosis, were followed for 20 years after their initial hospital admission. The first follow-up occurred two years after they left the hospital, with additional follow-ups at 4.5, 7.5, 10, 15, and 20 years post-discharge (Harrow and Jobe, 2007; Harrow et al, 2022).

Recovery was defined in a cross-sectional manner (over a 1 year period at the time of follow-up) and required absence of major symptoms throughout the follow-up year, adequate psychosocial functioning, and no psychiatric rehospitalizations during the year.

For almost the entire 20-year period, those not on antipsychotics at the time of the follow-up had higher functioning compared to those on it. Those not on antipsychotics were also much more likely to be in a state of recovery compared to those on antipsychotics.

In contrast to the Wunderink et al study above, where the two groups had similar symptomatic remission at the 7-year mark (and differed on functional recovery), in the Harrow study, those on antipsychotics are also more psychotic compared to those not on antipsychotics.

This is a big clue that what we are seeing in the Harrow study is natural history differentiation and not a causal effect of antipsychotic medications (in addition to the fact that the naturalistic, observational design is inadequate for establishing a causal relationship to begin with). Unfortunately, Harrow et al. are also the most egregious among the authors discussed here (especially in their later publications) when it comes to unjustifiably presenting these long-term outcomes as effects of antipsychotics.

The “never prescribed antipsychotics” group is likely to be enriched with the “never psychotic” (during the follow-up period) group, and since the never psychotic group is naturally on a long-term remission with good outcomes trajectory, this biases the outcome associations we observe. There is also likely be a strong overlap between the “intermittently psychotic” and “intermittently prescribed antipsychotics” group such that those prescribed antipsychotics at any given cross-sectional follow-up are those who are experiencing or those who have recently experienced an exacerbation of psychosis.

Much is made, by the authors and by some commentators, of the fact that even among those who were estimated to have a poor prognosis at baseline in the Harrow study, outcomes were worse for those on antipsychotics. Again, this is similar to the Wils et al finding above. Even among those with chronic symptoms, those who successfully discontinue antipsychotics are systematically different from those who are unable to discontinue or those who discontinue and then have to resume. In the Harrow study, those not on antipsychotics at the 15 year follow-up had better prior functioning, had more internal locus of control, better self-esteem, better prognosis at baseline, and better premorbid developmental achievements. The only way to demonstrate otherwise is randomization or a rigorous control of confounding factors.

In the Lancet Psychiatry meta-analysis, there is a clear difference between randomized and non-randomized designs. Randomized trials favor maintenance treatment and non-randomized trials favor discontinuation. The most likely explanation for this is natural history, differences in psychological and developmental characteristics, and availability of psychological and social resources.

My suspicion is that if we could randomize people for long-term studies lasting more than 2 years (which is almost impossible in practice; the drop-out rates would be astronomical), we would continue to see that dose maintenance outperforms dose reduction/discontinuation with regards to relapse prevention, however, I am uncertain about effects on quality of life and functioning.1

Taking into account natural history, functioning, and effects of antipsychotics

To recap…

»Trajectories of clinical course of psychotic disorders:

Long-term remission of symptoms after initial episode(s) of psychosis — probably around 20% but varies from study to study

Recurrent episodes of psychosis with psychosis-free intervals

Chronic, persistent psychosis

»Antipsychotics reduce psychotic symptoms, they reduce the risk of relapse, they have modest benefits on functioning (at least in the short term and up to about a year), and they probably reduce mortality, but they don’t change the long-term trajectory. Any long-term, observational study of antipsychotic use risks becoming a naturalistic study of the long-term course of psychotic disorders.

»Those who successfully discontinue antipsychotics are systematically different from those who are unable to discontinue or unsuccessfully discontinue and then resume. They are likely to be either folks who are naturally on the long-term remission trajectory, or they are folks with chronic symptoms who have the psychological and social resources to manage symptoms without antipsychotic medications.

»Antipsychotic effects that can adversely influence functioning:

Anticholinergic effects (including cognitive impairment)

Sedation (including neuroleptic effects such as feeling numb, indifferent, and blunting of motivation and drive)

Weight gain

Akathisia

We should expect these problems to be worse with high doses, higher than standard doses, and with polypharmacy.

Who doesn’t need antipsychotics?

There are three situations in which it could be said that you don’t “need” antipsychotics

You are in the long-term remission trajectory (unfortunately no way to accurately know in advance).

You can cope with your psychotic symptoms equally well via psychological and social interventions alone (a poorly characterized subset).

A third category would be situation where antipsychotics are warranted but prove to be ineffective or not tolerated (i.e. with adequate trials of multiple antipsychotics, including clozapine). Probably around 30% of people with schizophrenia don’t respond to standard antipsychotics and around 15% don’t respond to clozapine. Almost everyone is able to tolerate at least some of the available antipsychotics, but the ones tolerated might not be the ones effective.

Net effect of antipsychotics on functioning

If you stay on antipsychotics when you could’ve safely gotten off them (because you happen to be among those in a long-term remission trajectory or because you are in the poorly characterized subset of folks who can manage equally well via psychological and social interventions), the net effect on your functioning is likely negative.

If you go off antipsychotics that were effective for you, and they caused minimal side effects and you tolerated them well, and if you have a recurrent or chronic form of psychotic illness, then you are at a higher risk of experiencing future episodes/exacerbations of psychosis, and your functioning is likely negatively affected by discontinuation (i.e. the net effect of antipsychotics on your functioning is positive).

If you go off antipsychotics that were effective for you and they caused substantial side effects, and if you have a recurrent or chronic form of psychotic illness, your functioning may improve or worsen depending on which—psychosis or medication adverse effects—has a bigger negative impact on your functioning.

If you go off antipsychotics that were largely ineffective for you and you have a chronic persistent form of psychosis, your functioning may either stay the same (if you had minimal side effects) or may improve (if you had substantial side effects)

Scenario #1 probably applies to around 20% of people with first-episode psychosis (and to an uncertain percentage of people with multi-episode psychosis). They usually discontinue medications on their own, stay well, and don’t really come into contact with clinical services. But many of them will be in clinical care, and you have to actively consider dose-reduction and discontinuation as an option after a period of stability following psychosis, especially first-episode. (If, in 2024, you are still one of those clinicians who tell people with first-episode psychosis that they will have to take medications for the rest of their lives, you need to stop now!)

For people with recurrent psychosis who try dose reduction and discontinuation, they either find that they cannot successfully discontinue because psychotic symptoms immediately return or they end up restarting antipsychotics for acute treatment at a later point when they experience psychosis again. Some people in scenario #3 may find it preferrable to use antipsychotics only for acute treatment, but this is generally a risky move, as many lose insight during acute states of psychosis, and there are serious legal, financial, and social risks to consider (incarceration, homelessness, alienating family, etc.) in addition to the disruption that hospitalization brings.

An important factor with regards to functioning and/or successful antipsychotic discontinuation is the availability of competent psychotherapists who are skilled in working with people with psychotic disorders. This is especially the case for those with recurrent or chronic symptoms. The people that I’ve seen successfully discontinue antipsychotics tend to be people with high premorbid functioning, who are highly motivated, engaged in psychotherapy, with good psychological insight, and with strong social support.

All this demands personalization of antipsychotic treatment.

This is rather obvious in many ways, but unfortunately most clinical services continue to insist on long-term maintenance treatment for everyone and fail to support (or adequately guide) dose-reduction and discontinuation — driven by conservatism, paternalism, risk aversion, and outdated knowledge. On the other hand, in many critical and survivor spaces hostile to psychopharmacology, antipsychotics are demonized and everyone is encouraged to discontinue.

Any current attempt at personalization of antipsychotic treatment will be crude and uncertain, but it is what patients deserve.

Lex Wunderink puts it well, and I will end with this quote from him:

“Anyway, until we understand more about the routes to psychosis probably the best guide to antipsychotic treatment strategies apart from general evidence on relapse rates and the scant data on functional outcome, is preliminary personal risk-profiling (course characteristics, former relapses, danger during relapse) together with personal preferences… Substantial dose reduction is often feasible, and approximately 35% of patients presenting with a first episode of psychosis will even be able to discontinue completely, without experiencing a relapse. It is important to realize that substantial dose reduction might offer an equal improvement of functional capacity and alleviation of other side effects as complete discontinuation would have done.

Perhaps the question should not be whether to maintain or discontinue antipsychotics, but to find the lowest effective dosage to optimally prevent both relapses and side effects, and to allow optimal functional recovery. Finally, we have to conclude that a future differential approach, based on individualized profiling of the psychosis spectrum, is crucial to improve outcome of psychotic disorders. Even small steps forward will easily outperform the current one-size-fits-all approach.” (Wunderink, 2019)

See also:

There are also other elements of care that are often associated with the use of antipsychotics (but aren’t directly related to antipsychotics) that can adversely influence one’s long-term functioning. I’m not examining this in any detail, but very briefly, I’m referring to factors such as:

Clinicians encouraging patients to remain on disability (even when they could potentially work) and/or tempering their ambition for what they should seek to achieve in life.

Clinical services reinforcing stigmatizing narratives such that the patients see themselves as inherently dysfunctional or permanently damaged.

Lack of access to psychosocial interventions, such as individual psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral case-management, hearing voices network, etc.

Thanks for this excellent review. Also, I appreciate you raising questions about the Harrow findings, which one would expect if patients stop taking their antipsychotics when their psychosis goes into remission (rather than patients experiencing remission as a result of discontinuing antipsychotics).

As the parent of an adult with an early-onset psychotic disorder, I have noted changes of opinion over the past 20 years that often seem as driven by popular psychology as tied to strong evidence. Should antipsychotics be prescribed in the prodromal stages as a hypothetical preventative, or does that risk putting patients who may never develop a psychotic disorder on unnecessary medication? Claims about the effects of antipsychotics have varied from them needing to be taken lifelong (as already noted and critiqued in this article); to being necessary as an intervention against kindling of brain pathways (while some articles have found patient response to antipsychotics is not much worse among patients with longstanding untreated psychosis when compared to those who received early intervention); to being neuroprotective or even stimulating growth of grey matter; to disagreements about whether brain shrinkage is related to antipsychotic use or is a symptoms of the disease and even whether the amount of brain shrinkage is clinically significant (since patients with much more brain missing due to developmental variation or injury are doing just fine). Authors of journal articles reach different conclusions based on investigations of patients naive to antipsychotics, those using antipsychotics for a short time, and those with a history of longterm antipsychotic use. One article a number of years ago found higher-than-recommended doses of olanzapine to be similar in efficacy to clozapine. And a recent comparison of long-acting injectables found some to be statistically as efficacious as clozapine, making me wonder if the required monitoring of clozapine use is a partial explanation for its higher efficacy. Earlier this year, an article in the UK raised concerns about the elevated risk of sudden death associated with clozapine. If suicidal ideation is not an issue for a particular patient, if they have a strong family history of heart disease, and they are able to function despite the positive symptoms of psychosis, does that mean clozapine is counter-indicated due to its elevated risk of iatrogenic harm? It's a rhetorical question.

Similarly there have been disagreements about the pros and cons of mood stabilizers including lithium, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine with arguments that some are more effective than others, some may be neuroprotective, one or more may reduce suicidal ideation, and maybe some are more suitable for adults or children. Twenty years ago, popular thinking seemed to be that lithium was ineffective in children and carbamazepine must be used. A local residential treatment center was so enamored with oxcarbazepine a decade ago that they used it exclusively in their patients and often at doses much higher than manufacturer recommendations (which may be somewhat arbitrary). Similarly, while lithium has often been called the gold standard for mood stabilization, that position has been challenged by papers that disagree on whether it reduces suicidal thoughts, whether it is neuroprotective, and whether it causes kidney damage over time. Who should one believe?

Parents like me rub their heads and wonder how they are supposed to make an educated choice for the care of a family member--they can get a different opinion from each doctor they visit. Novice advocates and journalists read this stuff, choose their favorite journal article, and use it to make the policy arguments they prefer. This is one reason why it is impossible to agree on mental healthcare policy: We have advocates for medication, therapy, social supports, and so forth with academicians who hold terminal degrees in their fields disagreeing with one another. Anti-psychiatry activists including the Church of Scientology use these disagreements to malign the medical model and attack the entire medical speciality. The biggest losers are patients with the more serious and intractable psychiatric illnesses who are homeless on our streets and in our prison cells.

Thank you for the thorough, balanced, and nuanced review, Awais!

For those of us who spent the bulk of our professional careers caring for severely ill patients with chronic schizophrenia [1], your conclusion is entirely on the mark; i.e.,

"If you go off antipsychotics that were effective for you, and they caused minimal side effects and you tolerated them well, and if you have a recurrent or chronic form of psychotic illness, then you are at a higher risk of experiencing future episodes/exacerbations of psychosis, and your functioning is likely negatively affected by discontinuation (i.e. the net effect of antipsychotics on your functioning is positive)."

Patients fitting this description should be encouraged to continue their antipsychotic medication, with careful attention paid to managing side effects; e.g., using the lowest effective dose of medication. I would also note the need for greater use of clozapine, which is known to reduce suicidality in schizophrenia and--in my experience--can vastly improve quality of life. Psychosocial treatments are also an important component of care, for patients with chronic schizophrenia.

One important study to consider is that of Beasley and colleagues. This 52-week, double-blind, relapse prevention trial tested whether stable patients with schizophrenia who were taken off active drug treatment would experience greater improvements in long-term quality of life than those who were continued on antipsychotic treatment. The study found that, on average, Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality-of-Life Scale total scores improved by 4.3 ± 10.6 points during treatment with olanzapine (10 to 20 mg/d; n = 212), but decreased by 7.1 ± 14.6 points during treatment with placebo (n = 92; P < .001). The researchers also found that “. . . stable patients with schizophrenia who were taken off active drug treatment experienced no greater improvements in long-term quality of life than those who were continued on antipsychotic treatment, even in the absence of psychotic symptoms.” [2]

All that said, we need many more randomized, long-term studies of antipsychotic medication before reaching any confident conclusions of their long-term risks and benefits.

Ronald W. Pies, MD

1. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/quality-life-and-case-antipsychotics

2. Beasley CM Jr, Sutton VK, Taylor CC, et al. Is quality of life among minimally symptomatic patients with schizophrenia better following withdrawal or continuation of antipsychotic treatment? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:40-44.