Mixed Bag #25: Kinnon MacKinnon on Trans Identity and Medicine

“Mixed Bag” is a series where I ask an expert to select 5 items to explore a particular topic: a book, a concept, a person, an article, and a surprise item (at the expert’s discretion). For each item, they have to explain why they selected it and what it signifies. — Awais Aftab

Kinnon Ross MacKinnon, MSW, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Social Work at York University in Toronto, Canada. He teaches classes in critical social work, critical mental health, and social science research. Kinnon completed doctoral and postdoctoral training in public health sciences at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto. For over a decade, his scholarship has focused on transgender medicine, examining clinical practices and how gender minority populations experience hormonal and surgical treatments for gender dysphoria. Kinnon’s forthcoming co-authored book project (with Pablo Expósito-Campos) is titled Understanding Detransition (under contract with Polity Press). Learn more about him here.

To learn more about detransition research, follow The One Percent on Substack.

Surprise Item – “Kinnon MacKinnon”

I’m going to shake things up a bit and do the Surprise Item first, and share a bit about my name. “Kinnon MacKinnon” is a conversation starter, for sure. In person after I say my name, I’ve had responses like: “Wow, your parents must really have a sense of humor!” (Of course, they say this not knowing my trans history, and that I actually participated willingly in this ostensible joke, lol). In online contexts, though, where my trans status is more easily known, I’ve seen instances of gender-critical critics of my research take shots at my name. (“Man McMan” is perhaps my favorite gender-critical reinterpretation of “Kinnon MacKinnon.”)

I started transitioning socially (and then medically) just a couple of years after I moved away from my home province of Nova Scotia to relocate in Toronto. I grew up in a small Scottish-Catholic diaspora town of about 5,000 people: Antigonish, Nova Scotia. The “Mac” section of the phonebook comprised at least half of the listed numbers. There, dozens of men, including my step-grandfather, were called “Donald MacDonald.” Antigonish has the longest-running Highland Games outside of Scotland and holding a Scottish identity is common in my hometown. I grew up quite athletic, competing in Highland Dancing and a few other sports. I was not very good at the “girl” dances but I brought home dozens of medals in the dances that were traditionally performed by men, like the highland fling and the sword dance. I have a MacKinnon tartan kilt hanging in my closet here in Toronto and I can still do a decent fling!

I changed my name to “Kinnon” around the age of 24, while I was exploring my identity, and settling into Toronto while longing for home. Today, at the age of 40, I’m not quite sure I would choose that name for myself again, but I’ve had it now for almost my entire adult life. While the siren call of “Man McMan” is certainly seductive, I’m going to ride it out with “Kinnon.”

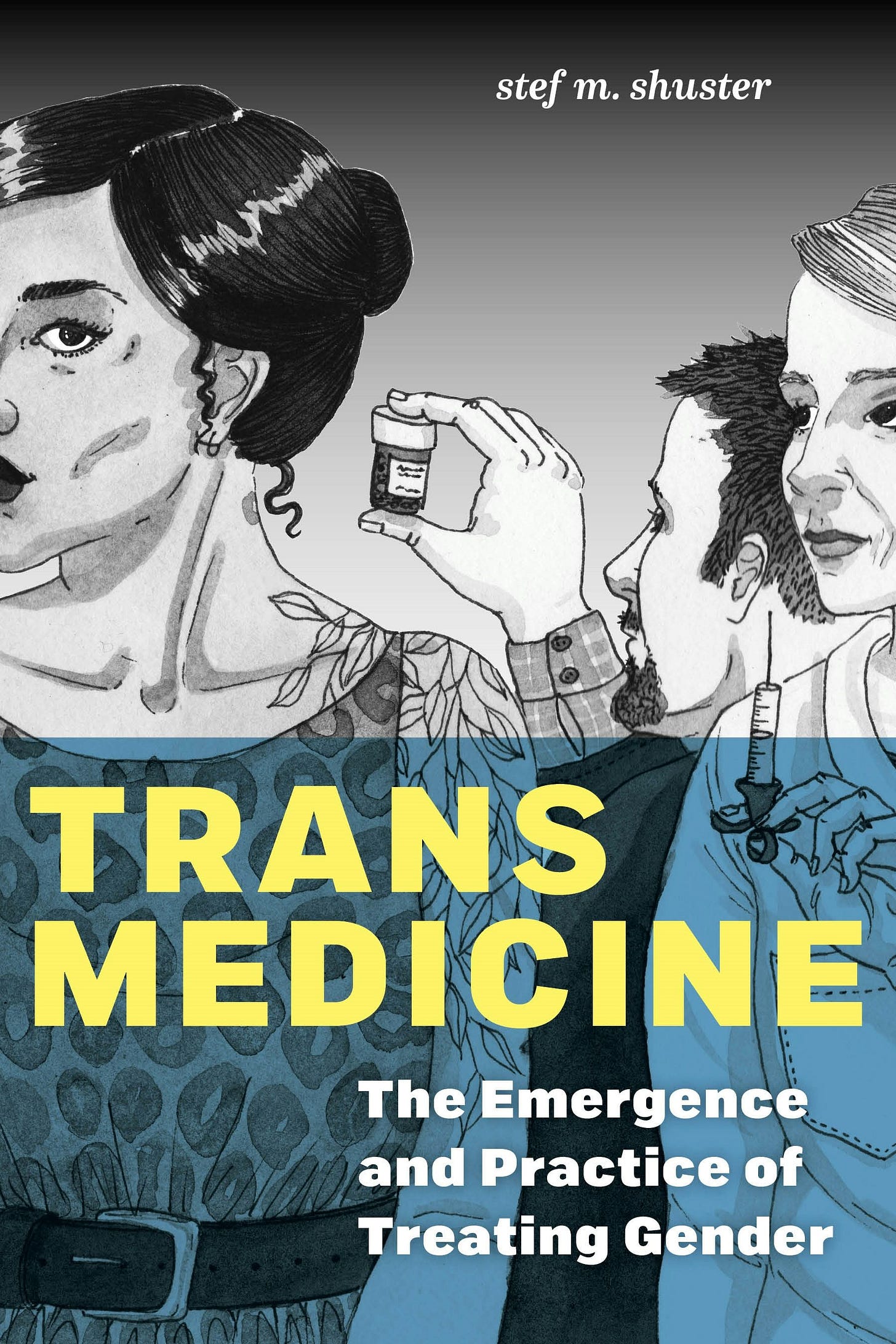

Book – Trans Medicine: The Emergence and Practice of Treating Gender (2021) by stef m. shuster

It was difficult not to choose something written by Foucault for this activity, as I read him frequently during my master’s and PhD. Poststructuralism, queer theory, and mad studies all had big impacts on me intellectually. While I’ve slowly evolved to become more of a pragmatic post-positivist over the years, the critical, theoretical stuff is in my bones.

So for this exercise I chose the book Trans Medicine. It’s written by Trans Studies scholar, stef m. shuster (they/them). shuster is an American sociologist at Michigan State University. The book is a deeply researched analysis of American transgender medicine from the 1950s to the mid-2010s. It examines the early establishment of US gender clinics and the normative ideas that underpinned doctors’ criteria for selecting patients for gender reassignment (spoiler: access to sex change treatment back in the day was based largely on whether the person requesting hormones/surgeries was anticipated to be able to blend into society as heterosexual and cisgender). The book presents archival research (letters shared between early American clinician pioneers, such as Dr. Harry Benjamin and his colleagues) before moving to contemporary qualitative interviews with gender clinicians. From this, shuster raises questions about how evidence for gender medicine has been constructed over time and how clinicians navigate and make decisions in scientifically uncertain terrain.

Interestingly, shuster’s clinician interviews were conducted with American gender clinicians around 2012-2015, a period of rapid expansion and transformation in trans medicine. Since the book was published in 2021, we have lived through yet another rapid transformation with new legal age restrictions on trans medicine having been introduced in many jurisdictions.

For anyone who reads the book today with the benefit of hindsight, it’s prescient in several parts. Many of the clinicians talked about how they were carefully navigating uncertainty in gender medicine. With these being high-stakes clinical decisions, shuster’s research uncovered a few strategies that clinicians deployed in response to uncertainty, such as evoking the rhetoric of EBM—calling the treatments “evidence-based” in the absence of high-quality longitudinal research or RCTs. Other clinicians minimized uncertainty by strictly adhering to the standards of care (meaning they were following an assessment model, also known as “gatekeeping”). These clinicians who worked “by the books” said they feared that cases of transition regret/detransition might provide conservative politicians “the tools they need to remove trans medicine from insurance plans, and trans identification from federal policies” (p. 107). (Note: This has indeed come to fruition in the USA and elsewhere). On the other hand, some of shuster’s clinician research participants said they worked around the standards of care, meaning they were not conducting the recommended psychosocial assessments and instead referred patients for gender treatments on the basis of an expressed desire, to facilitate treatment access rooted in trans people’s self-determination.

Trans Medicine lays bare major philosophical, scientific, and ethical debates that polarized the field over last 10 years or so, raising key questions that are still ongoing today: Should access to hormonal/surgical treatments be facilitated based on the sole condition of an expressed desire (and informed consent), or should it be based on rigorous research and a clinical diagnostic process to determine who might be likeliest to benefit from transition-related medical interventions?

Concept – Regret/Detransition

I am fascinated by historical gender medicine clinical literature. I started devouring the older stuff a few years ago when I was trying to make sense of my own contemporary research on detransition/regret; there was virtually no research on transition regret conducted from the early 2000s until about 2021, so I started to read what the old clinicians had to say about it. Through the process I realized that the field of transgender medicine had never arrived at any clear consensus on how to objectively measure transition regret/detransition. So, some of us, myself included, are now engaged in that task today (and this work is also what attracted me to Psychiatry at the Margins).

In its early professionalization period gender clinicians (together with government gender change policies) required binary transsexual transitions. That is, the clinical care protocols stipulated moving from male-to-female or female-to-male; gender clinicians were essentially chaperoning patients’ “gender role reassignment,” and they signed off on the legal gender status change as well. So when patients showed unexpected post-treatment behaviors, clinicians took notice. For example, if a patient shifted their gender presentation post-treatment, or detransitioned back to their original gender socially or legally, they were classified as having “regret.” Sometimes this regret classification was not based on the patient actually expressing regret with their medical decisions, whereas in other cases the patient had indeed developed iatrogenic gender dysphoria from the hormonal/surgical treatments and they sought to reverse body changes surgically. Whenever clinicians observed something other than a binary, linear transition from a stereotypical female role to a male gender role or vice versa it was often interpreted as signifying some degree of “regret” and failed clinical efforts. The term “regret” was always used heterogeneously in the older literature. Today, the term “detransition” has largely taken its place, and we have an emergence of some people who claim a “detransitioner” or “detrans” identity.

The term “detransition” evokes the notion of a transition reversal or of an undoing. In reality, one could raise questions about whether it’s possible to “reverse” a gender transition, because it’s an unfolding, psychological, social, and material process. Some detransitioners will say there is no going back, no reversing it (especially after surgery) while others may say they are building on a prior transition, it’s more of an identity evolution. So I have suggested interpreting the “de” in the concepts “detrans” and “detransition” in its Latin root (de=of/from). In other words, “detrans” could be interpreted as being from transgender origins, even if someone no longer affirms a transgender or nonbinary identity in the present.

In some earlier writing about regret, clinicians’ writing seemed to indicate blame toward the patient for a “wrongful” transition. Some papers suggested that a patient was misdiagnosed because of being “untruthful” with doctors. The term “regret” itself personalizes medical decisions within a narrow, individualized choice framework, indicating a mistake was made. Of course, this is not unique to transgender medicine. It’s part of a broader medical tradition of locating the source of a “bad” outcome within the patient themselves. “Regret” in trans medicine can function a bit like “treatment-resistant depression” or labeling a patient who persistently complains about not getting better as “difficult.”

By defining the central problem of detransition or non-linear gender transition outcomes as one of “regret” (an internal, negative emotional state within patients), the pioneering clinicians subtly sidestepped more difficult questions about diagnostic certainty and potential risks and limitations of the interventions themselves. Worse, “regret” has also been used to imply that trans patients can be sneaky tricksters, accountable for their own bad decisions.

But I also wonder if, for some of these pioneering clinicians, labeling patients with “regret” sheds some light on their own feelings about their patients’ outcomes. Gender medicine has always been quite fragile and contested; in the early days hospital boards expressly worried about litigation and bad press. As a result, significant clinical resources were invested in each patient; a long assessment process lasting up to several months or years, signing off on hormonal treatments, sex reassignment surgery, and legal gender reassignment. In other words, given the huge time, emotional, and economic investment in each individual gender transition, whenever clinicians observed these unexpected outcomes, patients were given the stamp of “regret.” But I think it’s possible that in at least some of the cases, the clinicians could have felt this emotion more deeply than the patients. It’s hard to say, because so few personal accounts or psychological data are available.

Person – Leslie Feinberg (he/she/ze; 1945-2014)

American butch lesbian, transgender activist, Leslie Feinberg, was among the key figures known for popularizing the term “transgender” back when notions of transness were defined by ‘psy’ clinician-scientists and sexologists. Before the word “transgender,” there were two types of trans recognized academically: transsexuals who medically transitioned to live as the “opposite sex” and transvestites who cross-dressed part-time, more for sexual expression. The term “transgender” disrupted prevailing academic knowledge. Feinberg was also the author of the seminal queer novel, Stone Butch Blues, and he lived as a transsexual man for several years before leaving the “sex-change program,” as he wrote in a 1980 autobiographical piece titled Journal of a Transsexual:

“I am a very masculine woman. Perhaps that is the easiest way to introduce myself. I lived convincingly as a man for four years on a sex-change program before leaving that program. I am a woman. I am the way I am. It is a fine way to be.”

It’s important to note that Feinberg was writing before the distinction between sex and gender identity became popularized; “woman” was synonymous with “female.” Feinberg was not asserting a cisgender woman identity, and he went on to become a major transgender activist, writing the book Transgender Warriors in 1996 and continuing to advocate for a definition of transness untethered from medicalized transsexuality. Feinberg’s account is remarkable because it challenged the tidy narratives of binary transsexualism of the era.

Rather than expressing regret or clinical failures, Feinberg framed their transition experience as one of reclaiming bodily autonomy and of radical acceptance of female masculinity, asserting: “I took back control of my body after four years on the program” and “I am the way I am. It is a fine way to be.” We see these types of narratives with some detransitioning people today.

Article – A Latent Class Analysis of Interrupted Gender Transitions and Detransitions in the USA and Canada (2025)

I’m going to pitch my team’s recent article here and encourage anyone interested in trans medicine, LGBTQ+ young people, and gender-affirming healthcare to check it out to learn more. Short summaries of the paper are available here and here.

One of the goals of this study was to generate greater conceptual and dimensional clarity regarding detransition while also generating clinically relevant information. While detransition still appears to be a minority outcome among those who transition, in absolute numbers it does appear to be occurring more frequently now (especially among LGBTQ+ young people born female who have more fluid identities, and who report a high burden of psychosocial complexities). Detransition/regret can have a major impact on individual patients’ lives, and on the field of transgender medicine overall, so it’s crucial for us to better understand these types of outcomes.

See previous posts in the “Mixed Bag” series.

Psychiatry at the Margins is a reader-supported publication. Subscribe here.

Interesting read! Long post ahead (but, for once, it's NOT about myself this time ;-) )

"Detransition" is often used so broadly, like McKinnon says. First of all, I think there's a really important distinction between transitioning socially (names, pronouns, style) and then going back, and having done medical treatments that may be more or less reversible/irreversible.

Then, obviously, you can detransition for different reasons, more or less internal/external.

In Sweden, there's the pretty famous case of Johan Jenny Ehrenberg, head of a left-wing media company. They began transitioning MtF in the eighties and the whole thing was super public; they appeared in both theirs and other magazines, on talk shows, etc. Then, they went back to "cis man". It became some sort of established truth in people's eyes that the whole thing had been nothing but a publicity stunt, but I thought all along that it did NOT seem like that at the time. It seemed honest, everything that J.J.E. wrote.

Waaaaay later, they began expressing some regrets about their DEtransition. They talked about both how trans care in the eighties was extremely binary, and the huge amount of hate and threats they received. "Maybe", they said, "if things had been different, I wouldn't have back-pedaled all the way to 'regular man' ". Even later, in their old age and with a cancer diagnosis that made it uncertain how many years they had left, they came out as non-binary, and added the name Jenny (which they had once used as a woman) to their birth name Johan, became "Johan Jenny".

It used to be the case that medical transition was seen as a package deal, no exceptions; if you do some things, you gotta do them all. People who transitioned during that time are, sometimes, happy with some of their treatments but regret, e.g., being pressured into having bottom surgery.

In Sweden (similar story in many other European countries) you had to be sterilized, and you were not allowed to save any eggs/sperm, in order to transition, up until 2013. Being forcibly sterilized is obviously a tragedy for everyone, and people might regret their transition and wish they had stayed in the closet for THAT reason. (I write this hypothetically, I don't personally know anyone forcibly sterilized who say they regret transitioning at all bc it came with sterilization attached. But might be some cases.)

Even fairly recently, some people went to clinicians with fairly conservative views on gender, and were pressured into either abandoning the whole idea of transitioning OR conform to conservative gender roles and present that way. I know some people just pretended to be these perfect men/women, planning all along to change that later. But others internalized more or less of that pressure. Later on, still happy with their bodies, they would, e.g., re-identify as non-binary or more fluid identity-wise, not as "man" or "woman".

Perhaps the opposite thing are people who really want to be the other gender than the one they've hitherto been identified with - but find that they can't, really, at least not socially, and then they'd rather backtrack. I saw some anti-trans people a while ago posting a news story about a middle-aged man, now once again identifying as such, who had begun a medical transition process and then back-pedaled.

"Concerned" anti-trans people: "This is so problematic, there should be more research before we let people do this".

The actual guy in the news story: "I realized I can never be a woman. I just felt like something in-between, and then I thought I'd rather go back."

Is this best described as regretting transition ... or as regretting how LATE he had a go at it? At an age where he's destined to LOOK "in-between", with all the consequences this might entail both socially and for his self-image?

And then you've got people who just regret the whole thing, it just wasn't right for them. Obviously the goal should be that this group remains small. But people in the debate sometimes seem to think that even ONE such person remains unacceptable, and a reason to shut down all trans care. Which is absolutely bizarre standards for trans care, standards applied NOWHERE else in medicine. All treatments have their regretters.

For some people, it's like suffering closeted trans people means NOTHING, but a single confused cis person who transitioned even though it was wrong for them has INFINITE negative value. They will also talk as if these confused cis people had zero agency in seeking out trans care, almost as if they were victims of coercive care. Which is both disingenuous and patronizing.