Playing Whack-a-Mole With the Uncertainties of Antidepressant Withdrawal

Complacency is the wrong conclusion of a new debated study

If you keep up with psychiatric research or pay attention to how psychiatry is discussed online, you’ve likely heard of the heated debate around a new systematic review and meta-analysis of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms in JAMA Psychiatry by Michail Kalfas et al. with Sameer Jauhar as the senior author (published online July 9, 2025). In fact, the controversy began before the paper was even published; while it was under embargo, prominent critical psychiatry accounts on Twitter started a campaign to preemptively discredit the paper. As far as I can tell, this only fueled interest in the study results, and the article has been covered by a number of prominent newspapers on its publication. For instance, see this well-written story about the article by Ellen Barry in the New York Times.

Ok, so what’s the fuss about? Here’s the plain language and the technical summary of the results as presented by the authors:

“This systematic review and meta-analysis of 49 randomized clinical trials found that on average, participants who stopped antidepressants experienced 1 more discontinuation symptom compared to those who discontinued placebo or continued antidepressants. The most common symptom in the first 2 weeks following antidepressant discontinuation was dizziness, and discontinuation of antidepressants was not associated with depressive symptoms.”

“Results A total of 50 studies were included, 49 of which were included in meta-analyses. The 50 studies included 17 828 participants in total, with 66.9% female participants and mean participant age of 44 years. Follow-up was between 1 day and 52 weeks. The DESS meta-analysis indicated increased discontinuation symptoms at 1 week in participants stopping antidepressants (standardized mean difference, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.23-0.39; number of studies [k] = 11; n = 3915 participants) compared to those taking placebo or continuing antidepressants. The effect size was equivalent to 1 more symptom on the DESS. Discontinuation of antidepressants was associated with increased odds of dizziness (OR, 5.52; 95% CI, 3.81-8.01), nausea (OR, 3.16; 95% CI, 2.01-4.96), vertigo (OR, 6.40; 95% CI, 1.20-34.19), and nervousness (OR, 3.15; 95% CI, 1.29-7.64) compared to placebo discontinuation. Dizziness was the most prevalent discontinuation symptom (risk difference, 6.24%). Discontinuation was not associated with depression symptoms, despite being measured in people with major depressive disorder (k = 5).”

A few things to keep in mind.

This analysis is not designed to tell us what percentage of people experience a withdrawal or discontinuation syndrome on stopping antidepressants, although it does look at the frequency of various individual symptoms associated with withdrawal. (The incidence of withdrawal was examined rigorously in a 2024 review and meta-analysis by Henssler et al.)

This analysis is not in a position to tell us how severe withdrawal symptoms are when they are experienced; it is looking more at what symptoms and how many, but not really at the severity or the associated degree of impairment. One of the primary outcome measures in the analysis was the Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS) scale. DESS is a 43-item instrument that assess signs and symptoms associated with of discontinuation antidepressants, and a score of 1 point is assigned to each new or worsened symptom. DESS doesn’t measure severity, and this is explicitly noted in Supplementary Materials:

“Although an increased DESS score may suggest increased severity, because individual symptoms are not graded on severity, it is possible that an increased DESS score may not reflect severity, e.g., inclusion of more less-concerning symptoms.”

Someone could have a low DESS score with high severity or a high DESS score with low severity.

This analysis did not seek to nor did it have the methodological tools to distinguish between antidepressant withdrawal and depressive relapse.

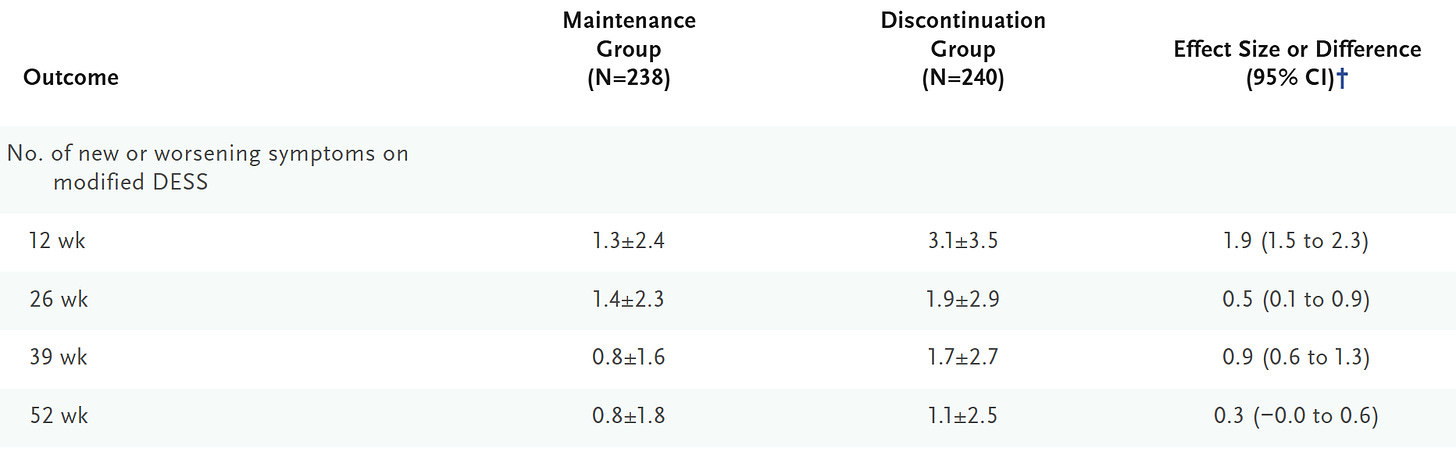

This analysis sought to be comprehensive, going so far as to include unpublished data from 11 clinical trials but it is still limited by the fact that most studies have a short duration of antidepressant treatment (around 8-12 weeks). It nonetheless did have some data from studies with a long duration of antidepressant treatment, including the rigorous and high-quality ANTLER trial with a treatment duration of more than 36 weeks (more than 70% people in the trial had a treatment duration more than 156 weeks).

This analysis was also limited by the fact that most studies had looked at discontinuation symptoms over a time frame of 1-2 weeks; ANTLER trial was again among the few exceptions.

Many common antidepressants were not well-represented in the analyses, including fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), and venlafaxine (Effexor). In case you don’t know, paroxetine and venlafaxine are the most notorious for causing withdrawal symptoms. There were also several trials of agomelatine, which doesn’t really have a withdrawal syndrome.

Given all these limitations, what then is the actual take-away from the meta-analysis?

A person who stops their antidepressant experiences on average 1 more discontinuation symptom compared to those who discontinue placebo or continue their antidepressant treatment.

In other words, the symptom burden related to withdrawal or discontinuation for the average user of antidepressants is quite modest.

If we look at specific symptoms, some symptoms do stand out in terms of increased likelihood: dizziness (Odds Ratio 5.5), nausea (OR 3.2), vertigo (OR 6.4), and nervousness (OR 3.15) compared to stopping placebo. [You know what’s missing in this list? Brain zaps! A very commonly reported symptom in clinical practice. This is because original DESS doesn’t include brain zaps as an item.]

We can say this with high confidence for short-term antidepressant treatment and with lesser confidence for long duration of antidepressant treatment.

This is not particularly news to most practicing psychiatric clinicians, but it does challenge a common narrative popular in critical psychiatry and prescribed harm circles: that antidepressant withdrawal is very common and often severe.

James Davies and John Read in a very methodologically-problematic 2019 paper concluded that 56% of people who (try to) stop antidepressants experience withdrawal effects, and nearly half (46%) of people experiencing withdrawal effects describe them as severe. These figures are obviously highly-inflated but are often treated with reverence in the harmed patient community.

Henssler et al. demolished these estimates in their meta-analytic review last year, which I consider to be the most rigorous estimates currently available.

“A clinically relevant proportion of patients will have adverse symptoms after discontinuation of antidepressants. Non-specificity of symptoms and both patients' and doctors' expectations probably influence the incidence of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms. Subtracting non-specific effects, the frequency of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms can be expected to be in the range of approximately 15% (roughly one out of every six or seven patients can be expected to have antidepressant discontinuation symptoms that are specifically attributable to discontinuation). About one in 35 patients will have severe antidepressant discontinuation symptoms. Discontinuation symptoms are most frequently observed with desvenlafaxine or venlafaxine, and particular caution due to severe antidepressant discontinuation symptoms seems to be warranted when discontinuing imipramine, paroxetine, and desvenlafaxine or venlafaxine.” (Henssler, et al. 2024)

Although Kalfas et al. provide neither an overall incidence for withdrawal nor an estimate for severe withdrawal, their results are in alignment with Henssler et al.

Basically, if you are still someone who treats the Davies and Read estimate of antidepressant withdrawal as valid—take the L and move on!

The data from clinical trials just doesn’t back it up.

Ok, but what about the relative lack of clinical trials with a long duration of antidepressant treatment? Surely if we had such trials, we’d see much higher numbers?

That’s commonly assumed by critics of antidepressants, and it seems plausible, but the little data that we do have doesn’t back it up.

In both Kalfas et al. and Henssler et al., longer duration of antidepressant use doesn’t translate into more symptoms, higher incidence, or higher severity.

“Meta-regression indicated no association between antidepressant treatment duration and discontinuation symptoms at week 1 (slope, −0.014; 95% CI, −0.04 to 0.00) or week 2 (slope, 0.007; 95% CI, −0.04 to 0.05).” Kalfas et al. 2025

“Meta-regression did not indicate significant associations of incidence with duration of antidepressant treatment…” Henssler et al. 2024

In their reply to commentators, Henssler et al. say more about this issue.

“With few studies extending beyond 1 year of follow-up, whether incidence of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms would be considerably higher after long treatment is currently unclear. However, from what we know so far (eg, from a regression analysis in table 2 of the original Article), incidence rates do not substantially rise with increasing treatment length. Even among studies with treatment duration of around 1 year or longer, the incidence is similar to the overall effect: 0·35 (95% CI 0·25–0·45). Of note, this result is based on 10 studies, with a total of more than 2800 patients, a broader evidence base than in the investigations mentioned by Read and Davies. An association of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms with treatment length is also questionable on theoretical grounds because this claim corresponds to tolerance development, which we do not find in antidepressants. Instead, it is possible that the body's counter-regulations in response to pharmacotherapy, which are presumably the basis of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms, take some time to develop but do not continue to increase progressively with treatment duration.” (Henssler at al. 2024)

I am open-minded on this issue and I think most people should be. There is considerable uncertainty. Maybe longer treatment duration does lead to more withdrawal. It has a certain plausibility, and it is aligned with what I tend to see in my patients (patients who’ve been on antidepressants for many years/decades tend to have the hardest time coming off). But the important thing is that as an empirical question, the answer cannot be taken for granted.

It cannot simply be assumed that longer antidepressant treatment will definitely lead to more antidepressant withdrawal and severity. Proponents of this belief actually have to demonstrate it now under rigorous conditions.

As I noted, the ANTLER trial is one of the few rigorous trials of antidepressant discontinuation with a long duration of treatment, and their results just don’t show people struggling en masse with withdrawal symptoms even though they had been on antidepressants for a long time before stopping.

And yet, I don’t think the Kalfas et al. paper helps settle genuine scientific disagreements around antidepressant withdrawal and likely won’t change many minds.

In a recent opinion essay for the New York Times, I had written:

“Now patients are likely to stay on antidepressants for years, even decades. Of those who try to quit, conservative estimates suggest about one in six experiences antidepressant withdrawal, with around one in 35 having more severe symptoms. Protracted and disabling withdrawal is estimated to be far less common than that. Still, in a country where more than 30 million people take antidepressants, even relatively rare complications can affect thousands of people.

This is why it’s a travesty that nearly four decades after the approval of Prozac, there’s not a single high-quality randomized controlled trial that can guide clinicians in safely tapering patients off antidepressants. The lack of research also means that official U.S. guidelines for it are sparse. It’s no surprise that patients have flocked to online communities to figure out strategies on their own, sometimes cutting pills into increasingly smaller fractions to gradually lower their dose over months and years.”

I was already writing under the assumption that withdrawal isn’t a big issue for the average patient, and the new paper by Kalfas et al. backs it up, but my main point was that we are still dealing with a clinically relevant subset of patients experiencing withdrawal and a much smaller fraction of people experiencing severe and disabling withdrawal who are nonetheless not getting the help they need, and this is creating a lot of understandable anger.

Antidepressant withdrawal may indeed be no-big-deal for the average patient, but this is no consolation to the minority who do experience severe withdrawal and who struggle to get adequate help from clinicians who are dismissive of their difficulties.

So while the results by Kalfas et al. are reassuring, we are still playing whack-a-mole with the uncertainties of antidepressant withdrawal.

We still cannot say with high confidence what percentage of patients experience severe withdrawal with long-term antidepressant use.

We still don’t know what instruments most accurately detect antidepressant withdrawal. DESS is clearly inadequate.

We still cannot say what tapering strategies produce the best empirical outcomes. We still don’t know what tapering under blinded and randomized would look like. [My own suspicion is that hyperbolic tapering would flounder under blind randomization.]

We still don’t understand very well the relationship between the emergence of depressive symptoms and antidepressant discontinuation. This is the thorny relapse vs withdrawal question. Kalfas et al say, “later presentation of depression after discontinuation is indicative of depression relapse” but I disagree; the methodology of their study is not designed to support an inference like this. I’ll believe it when I see a well-designed study. A reason for my skepticism is that I’ve personally seen patients who have experienced rapid and severe depression with suicidality and agitation—unlike anything they have experienced before—on abrupt discontinuation of antidepressant which rapidly resolved on reinstituting said antidepressant. A normal major depressive episode doesn’t behave like that.

We still don’t understand what’s going on with people who report experiencing protracted withdrawal that lasts months and years.

My worry is that the profession is going to leave with the wrong take-away from the Kalfas et al. paper. Complacency about antidepressant withdrawal is the wrong conclusion. The issue has become so emotionally charged precisely because we neglected it for so long. Regardless of what DESS score an average patient experiences, we would make a terrible mistake if we continue to ignore the people, our patients, who are suffering from or are at risk of severe withdrawal.

See also:

Great write-up

200+ different patients a week

Treated over 4 000 different patients

Never seen a "protracted withdrawal" lasting for years

I m not saying it doesnt exist, but I've never seen it

Will keep looking