Q&A with Pim Welle on the New York Fed Staff Report on Involuntary Hospitalization

“I’ve worked on many things in my life, and I have never once found a problem with such depth and complexity.”

Pim Welle serves as Chief Data Scientist at Allegheny County Department of Human Services. He holds an engineering degree from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a PhD in engineering and public policy from Carnegie Mellon University. His career has focused on developing statistical and machine learning systems for government institutions. Currently, he creates innovative tools within human services to evaluate system effectiveness and direct resources to individuals with the greatest needs.

He is one of the authors of the New York Fed’s Staff Report, “A Danger to Self and Others: Health and Criminal Consequences of Involuntary Hospitalization.” This Q&A is a follow-up to my discussion of the paper:

Aftab: What first drew you to this topic?

Welle: I started working at Allegheny’s Department of Human Services in 2023, and this was the first project I took on. The county was building its own staff of data scientists and I was one of the first through the door. Our director, Erin Dalton, asked me to take a look at involuntary hospitalization.

Quantitative research is an interesting thing because sometimes you start projects that seem like a good idea but don’t pan out, and other times there is quite a bit to explore. I’ve worked on many things in my life, and I have never once found a problem with such depth and complexity.

The first thing I did was crosswalk the list of individuals who had been hospitalized to other administrative sources. The results were astounding:

We saw incredibly high rates of all-cause mortality, with 20% (1 in 5) dying in five years

We saw incredibly high rates of spending, with 25% of our behavioral health dollars going to individuals with a recent history of psychiatric hospitalization

We saw very different behaviors between psychiatrists and non-psychiatrists, with psychiatrists choosing to hospitalize less than their counterparts

We saw lots of substance use disorder. Folks with co-occuring substance use disorder make up 31% of the data, and account for some of the worst outcomes

We didn’t see lots of homelessness—about 4% of the cohort will appear in our shelters at any point in the year following a hospitalization

It’s one of those stories that really just continues on and on, and it’s something we’ve been dissecting for the last several years.

In parallel to the data work, I spoke with physicians and people who had been hospitalized. It really seems that very few people are content with the current system. And that makes sense. On one hand, you’re depriving someone of liberty. On the other hand, if you do not, something bad may occur—something that may carry both moral and legal liability. When I asked one doctor how often he gets to the end of an exam and feels certain as to the decision he’s made, he paused for a bit and then said, “...rarely.”

So the short answer is we started looking, and the long answer is when we started looking, we just kept uncovering new facts about the system which pulled us deeper and deeper.

Aftab: What’s historically made this phenomenon so difficult to study? What kinds of barriers, scientific as well as institutional, have researchers run into?

Welle: There is very rich qualitative research in this space. Doing deep interviews with people who have been hospitalized is generally a great way to get a full picture of their experience, themes, and emotions. The worry with qualitative research, however, is that the number of individuals you can survey is small and they may be unrepresentative of the population as a whole (they might be more trusting, more highly educated, et cetera). This limits its generalizability.

Quantitative research in this space, on the other hand, has been much more challenging. The data are often not available. Allegheny County is the only county in Pennsylvania keeping digitized records of its commitments at all, and that’s because it built its own software to count and curate the data. Nationally, the only system keeping counts is the FBI firearms database National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), which is not available for research. The state of the data is so poor that we only have information about rates of involuntary hospitalization from 24 of the 50 states, despite every state having some sort of process for psychiatric detention. It’s worth hammering home this is an incredibly low bar—as a country, we largely don’t even have simple counts as to how often psychiatric holds are happening.

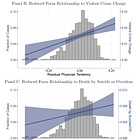

But beyond that, you ideally want to study the effects of commitments on other outcomes. Our main outcomes of interest in the paper are deaths by suicide/overdose (which come from the medical examiners) and violent crime charges (which come from the courts). Additionally, we look at employment and wages, medication refills, outpatient attendance, and usage of emergency shelters. None of our findings would be possible without that robust data linkage across different administrative sources.

So to the broader question of why this was possible, it’s some combination of record keeping, record linkage, the investment in institutional talent, and the collaboration with national experts on these topics and methods. All of those are somewhat rare individually, and I think that is why it’s been difficult for something like this to come into being.

Aftab: How did your collaboration with the co-authors come about? And who originally proposed using physician propensity to involuntarily admit as the instrument?

Welle: I was connected with Natalia Emanuel and Valentin Bolotnyy through professional networks. They are both incredibly detailed quantitative policy researchers. As to who suggested the use of physician propensity—I believe that was our analytics director Alex Jutca, who suggested it as an avenue when I started looking through the data.

In the quantitative social science literature there are a number of approaches that are established and have existing reputations. The sort of design we employ here has a shorthand of “judge instrumental variables,” or more commonly “judge IV,” because it comes from a literature of using randomly assigned judges, and exploiting their differential sentencing behavior. So while it may seem more exotic or strange in this particular domain (we are, as far as we know, the first people to apply such a technique), there is a class of researchers who you can speak to and say, “I’m running a judge IV on psychiatric commitments,” and they would know more or less what you mean.

Now within any quasi-experimental technique there are hundreds of design decisions and robustness checks that will differ between implementations. And these design decisions are crucial for recovering accurate treatment effects. Those sorts of decisions are what we’ve been working on for the past two years, and sharing with other researchers and getting feedback on.

Aftab: Were there any results that genuinely caught you off guard?

Welle: It’s cliche, but maybe all of them. I did not go in with priors for our main results. It was genuinely unclear which way it would break. The fact that it breaks towards causing harm to self and others was a surprise, and the effects are quite large.

Because of how academic publishing works, one result that I think gets too little attention is the result around antipsychotic refills. Our sample size is small and the results are not significant, but the magnitudes are large and show a suggestive decrease in the number of medication refills post-treatment. This makes sense if you go through a period of involuntary commitment where you perhaps have very little agency over what medications enter your body. While we can’t make strong claims here because of the sample sizes, I would love other researchers to continue studying the effects of commitments on engagement with medication.

Aftab: You’ve presented this data at multiple conferences. How have audiences reacted? Anything notable in the feedback?

Welle: In general, my coauthors and I have presented at two sorts of conferences and seminars—technical ones and subject matter ones.

For the technical conferences, we’ve gotten a host of feedback on different statistical checks, most of which ended up in the paper. We had the good fortune of presenting at one of the most prestigious economics conferences this summer; a recording of my co-author Natalia Emanuel presenting this work is available online.

For the subject matter conferences, we’ve learned more about the details of commitments, what happens in inpatient, and what other municipalities are implementing.

We’ve also heard from people on the ground—both people who have been committed, physicians and administrators in the hospitals we study, and outreach workers who have been involved with those processes. In general I’ve been surprised by how little pushback we’ve received, even from folks who manage and operate inpatient facilities. Something about this message seems to have rung true.

Aftab: Is Allegheny County unusual in how thoroughly it tracks data related to involuntary hospitalization? Or do other counties collect comparable information?

Welle: It’s going to differ at the state level, but Allegheny County has built its own digital system to track the process as it occurs, all the way from the initial calls to which doctor performs the evaluation. This is pretty unusual, at least in Pennsylvania. Other counties will track the commitments, but they may not be digitized or at all available. We’ve talked to many, many quantitative researchers who have run into serious impediments trying to make progress getting data.

Aftab: Are there features of Allegheny County that might limit how broadly these findings apply elsewhere in the U.S.?

Welle: This is going to be hard to say. Most of the idiosyncrasies are going to be at the state level, because that’s where these laws are governed. While each state has laws allowing for commitment, they are going to differ in who makes the decision, the length of time for commitments, and the process for extension.

From a numbers perspective, it is convenient that Allegheny County has about the same number of involuntary psychiatric commitments per capita as the United States as a whole (Allegheny County is at 307 per 100k, our best estimate for the country is at 357 per 100k).

Some examples:

In Pennsylvania, a single physician in an emergency department makes the decision on a hold of 120 hours. That physician can have any credentials. Extensions beyond the initial commitment are filed by the treatment team and go before a judge at the Court of Common Pleas.

In North Carolina, two separate physicians must agree to the hold within 24 hours, at which point a person can be held for 10 days until a judge reviews further extensions.

In Florida, the first 72-hour hold can be initiated by law enforcement or a clinician. Extensions beyond that go through the circuit courts. For these reasons, Florida has one of the highest rates of psychiatric commitments in the country, with over 900 people per 100k being committed each year.

Outside of the US, Trieste in Italy has long served as a model of community-focused care. They commit people at a rate of 8 per 100k.

So the process will differ in who decides and what the relative length of time between extensions might be. This is going to be a challenge in studying this phenomenon, one that will never be fully overcome. But the benefit of the variation of the legal processes is that the differences might allow us to better understand which systems work and which do not. But only if the data become available to continue studying.

Aftab: In a recent post, Freddie deBoer (Freddie deBoer ) challenged aspects of the paper’s methodology. Having spent considerable time in the past going through the analyses and discussing them with others, including you, it is clear to me that the objections are quite superficial and don't undermine the results. Still, for those less familiar with the details, the criticisms may seem persuasive. How would you respond to those criticisms, and can you explain why they don’t invalidate the conclusions?

Welle: What’s clear from the piece is that Freddie deBoer has a history of writing about psychiatric hospitalization and is in favor of making involuntary psychiatric hospitalization easier. He also has experience being hospitalized himself and credits that hospitalization with saving his own life. This will be true—there will always be folks who individually benefit from psychiatric hospitalization. There can be many reasons for this—they might, for example, be particularly treatment responsive to medications, they might be resourced and so resist the labor market scarring, or there might be softer reasons like the psychiatric hold itself becoming a sort of wake-up call. It is also possible that among cases where physicians agree (i.e., the really clear-cut cases) that a person should be involuntarily hospitalized, the hold is quite helpful. But what our paper suggests is that among the judgment call cases, on average, the net effect is negative.

Moreover, I think we are aligned with some of the pathos-based claims in his blog post. We agree that unaddressed mental illness can be painful, frustrating, as well as personally and societally damaging. The instances he cited may indeed have been prevented, and preventing such acts of violence is very important. I think we very much agree. Neither are we opposed to psychiatric care and hope that this piece is not used to argue against the application of psychiatric tools in a careful, thoughtful manner. On the contrary, I think it is clear that evolutions in that field have invariably resulted in a lot of benefit for patients and for families.

In terms of the critique of the statistical elements of the paper, Freddie’s piece brings up objections in a scattershot manner. I’ll try to address the highlights:

Doctors aren’t assigned randomly—First of all, that isn’t our claim. Of course some physicians work only at selected hospitals. Rather, our claim is that within a given shift, for first-time evaluations, it is random which physician attends the case. We arrived at our rules by talking with many physicians, understanding the triage protocols at the hospitals we are studying, and when those protocols might be violated. Now luckily, we can also validate this claim with the data. We can check whether a physician is associated with any observed variables, including the reason folks are hospitalized (e.g., suicidality, unable to care for self, et cetera), the number of times they use the emergency department, other services, and demographics. If any of those differ with physician tendency to hospitalize, the statistical check will fail. Yet we see that physicians are unassociated with the descriptive variables of the cases that they evaluate. There are always unobservables, but this is where the Allegheny County data really shines: we have access and can check this assumption against much more information than most jurisdictions.

The compliers are different from the non-compliers—This is fine, and to be expected. The compliers are the judgement-call cases. Folks who everyone agrees should be committed are very likely going to be very different from the folks physicians disagree about. The effect we’re estimating should be interpreted as comparing the hospitalized compliers against the unhospitalized compliers. In general, Freddie spends a lot of time on “Berkson’s Paradox” (often called “omitted variable bias” in the statistical literature), but that is a complete red herring. The entire setup of the analysis is structured to address that point.

The sample size is too small—While we should be worried about whether Allegheny County generalizes to the rest of the country, the sample size and our ability to validate our effects are not a problem. If we could not see an effect on the rare outcomes, the results would not be statistically significant.

Monotonicity assumption—Violation of monotonicity would be, for example, doctors behaving differently among some subset of the population. To check this, we can do two types of tests: first, we can see how consistent physicians’ tendencies to hospitalize may be among different groups of patients (e.g., those on Medicaid vs. those who are on private insurance; men vs. women, etc). We find that physician tendencies are fairly constant. Second, we can also predict physician tendencies among one set of cases and see how it relates to actual tendencies in the other set of cases (e.g., predict among those who have attempted suicide and relate to actual tendencies among those who have not attempted suicide). We find a high correlation. This suggests that on average, we don’t have a problem with monotonicity among the judgement call cases.

Quasi-experimental designs are tricky. This is why this paper has been in the works for such a long period of time. In general, we appreciate the discussion but haven’t found critiques in this piece that have not been brought to us in other settings or that fundamentally trouble us about the validity of the results.

Aftab: A question I’ve heard a lot after mentioning your paper: why was this released as a staff report? Can you say something about what that means in the context of the publishing process in economics research?

Welle: Many people may be used to the way articles are published in Medicine, where they are usually peer-reviewed before reaching a broader audience. That is almost never the case in economics. In economics, working papers (or staff reports) are released often before even being submitted to journals, let alone receiving feedback from referees.

This release of working papers is a reaction to the very long—sometimes years-long—publication process in the field. But it is also advantageous because many experts can give feedback before the final version is codified. In a similar vein, working papers are also presented to other economists before they are peer reviewed. Something I’ve heard said about economics is that if you only take published papers seriously, you will be a decade behind the field. We have done a lot of work to collect feedback and socialize this work, but are still collecting feedback from both economists and domain experts as we go through the publication process.

Aftab: What’s been the response from Allegheny County leadership? Have they expressed interest in using the findings to shape policy?

Welle: There is a large appetite to change policy. The county released a very detailed discussion in response to the paper which outlines policy avenues. I would encourage your readers to read through it.

Aftab: Involuntary psychiatric hospitalization is a very polarizing topic. Some advocate for a lot more of it, to the point of saying that we need to bring back asylums; others want it abolished altogether. Do you think empirical work like this has the potential to resolve some of these thorny, entrenched debates?

Welle: Resolve is probably too much to hope for, given the challenge in studying this phenomenon. But I do have a strong personal belief that high-quality quantitative work brings people together more than it divides.

Aftab: Where do you see this line of research heading next?

Welle: It’s hard to say. There are a few different directions I am interested in:

Replicating this work in other municipalities;

Mining the free text petitions to gain a deeper understanding of the circumstances governing the petition process; and

Conducting representative surveys of individuals who have been through psychiatric hospitalization

The last two directions have the potential to get the detailed benefits of qualitative work, but at a more comprehensive scale, which is something I am excited about.

Aftab: On July 24, the White House issued an executive order pushing for more involuntary psychiatric commitment for homeless populations. What do you make of this order in light of your findings?

Welle: One of the other major things I study is homelessness. This executive order was disappointing to see, because chronic homelessness is one of the few things that we know how to solve. There is very good quantitative research that suggests giving someone housing in the form of deep housing subsidies (things like Housing Choice Vouchers, Rapid Rehousing, Permanent Supportive Housing) basically eliminates homelessness during the period of support and even after the support expires. The problem is that (1) we have relatively few of these vouchers and (2) that these vouchers are not targeted at individuals who would have otherwise been homeless absent the voucher.

Using long-term psychiatric commitments as a solution here is not likely to work. In our paper we show suggestive evidence that psychiatric holds destabilize housing. But even if they did not, they are expensive and inefficient. In Allegheny County a single 10-day hospital stay can cost the government as much as 6 months of fair market rents. Long psychiatric holds are not going to be a major part of any comprehensive ethical policy response to homelessness.

Aftab: Thank you!

See also: other interviews in Psychiatry at the Margins fostering a re-examination of philosophical and scientific debates in the psy-sciences.