DSM Disorders Disappear in Statistical Clustering of Psychiatric Symptoms

Whither Major Depression?

“Reconstructing Psychopathology: A data-driven reorganization of the symptoms in DSM-5” by Miri Forbes, et al. (currently available as a pre-print) is a brilliantly designed and innovative study of the quantitative structure of psychopathology with important ramifications for our understanding of psychiatric classification. No one has conducted a study quite like this before, and the results are remarkable. It takes place in the context of the development of Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) which is a dimensional, hierarchical, and quantitative approach to the classification of mental disorders, and relies on identification of patterns of covariation among symptoms.

The study is based on a large online survey, with participants recruited from a variety of sources, resulting in a socio-demographically diverse sample size of 14.8K participants. Participants could opt to complete a mini, short, medium, or long version of the questionnaire. The survey consisted of items based on individual symptoms derived from DSM-5. Symptoms were written in first person and past tense, as close to the DSM phrasing as possible but devoid of information about symptom onset, duration, frequency, and severity. Importantly, survey items were presented to participants in a random order. This randomness is important because in prior studies questions about symptoms were not asked or presented in a random manner. They have been asked using symptom questionnaires that cluster symptoms together in ways influenced by the diagnostic manuals or using a structured clinical interview that adopts the DSM organization. Asking about symptoms in a random order ensures that their co-occurrence is not artificially influenced by the order in which questions are asked. The survey went through multiple rounds of pilot testing, and in the end, 680 items were included. Participants reported how true each symptom statement was for them in the past 12 months on a five-point scale from Not at all true (Never) to Perfectly true (Always). Participants were told to think about their experiences across a wide variety of contexts.

The responses were subjected to two statistical clustering methods: iclust and Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering. Clusters were accepted for further analysis when both methods agreed. This was intended to ensure that there were no idiosyncrasies arising from reliance on one method. This resulted in 139 clusters (“syndromes”) and 81 solo symptoms. Higher-order constructs were identified using hierarchical principal components analysis and hierarchical clustering. The sample was divided into a primary sample (11.8K) and a hold-out sample (3K) to examine the robustness of results. The final classification was based on points of agreement between samples and methods.

The final high order structure included 8 spectra: Externalizing, Harmful Substance Use, Mania/Low Detachment, Thought Disorder, Somatoform, Eating Pathology, Internalizing, and Neurodevelopmental and Cognitive Difficulties. 27 subfactors were identified. As an example, within the internalizing spectrum, the 4 subfactors were: Distress, Social Withdrawal, Dysregulated Sleep and Trauma, and Fear. Similar to earlier literature, a single overarching dimension also emerged. This has been described before as the “p-factor” (general psychopathology factor), but Forbes et al. chose to call it the “Big Everything” to avoid reifying it.

So here it is, an empirically derived hierarchical clustering of individual symptoms across the range of psychopathology:

The end result has a prominent convergence with the existing HiTOP model, with some points of divergence that would be important for future revisions of HiTOP.

An important thing to note is that many classic DSM disorders do not emerge as identifiable syndromes in these analyses.

Due to the symptom heterogeneity of DSM constructs, they are either broken down into smaller homogenous syndromes or they merge into higher-order clusters such as subfactors and spectra. (And this is the case not just in this particular study, but has been the case in prior analyses on which the HiTOP model is based—even though those exploratory symptom-level analyses had been conducted using measures based on DSM/ICD.)

There is much to discuss in this paper, but for illustrative purposes, I’ll focus on the case of depression and some other internalizing disorders.

“Major depressive disorder” (MDD) is one of the most common and recognizable disorders in psychiatry. Hundreds of thousands of people are diagnosed with MDD every day. Every medical student is taught the SIGECAPS symptoms that constitute the diagnostic criteria of depression, and across many clinics, people fill out the PHQ-9 screening questionnaire based on those symptoms. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are similarly common diagnoses.

What does it mean that MDD, GAD, and PTSD do not show up as coherent and distinctive symptom clusters in statistical analysis?

This is the internalizing spectrum as it appears in Forbes et al. 2023:

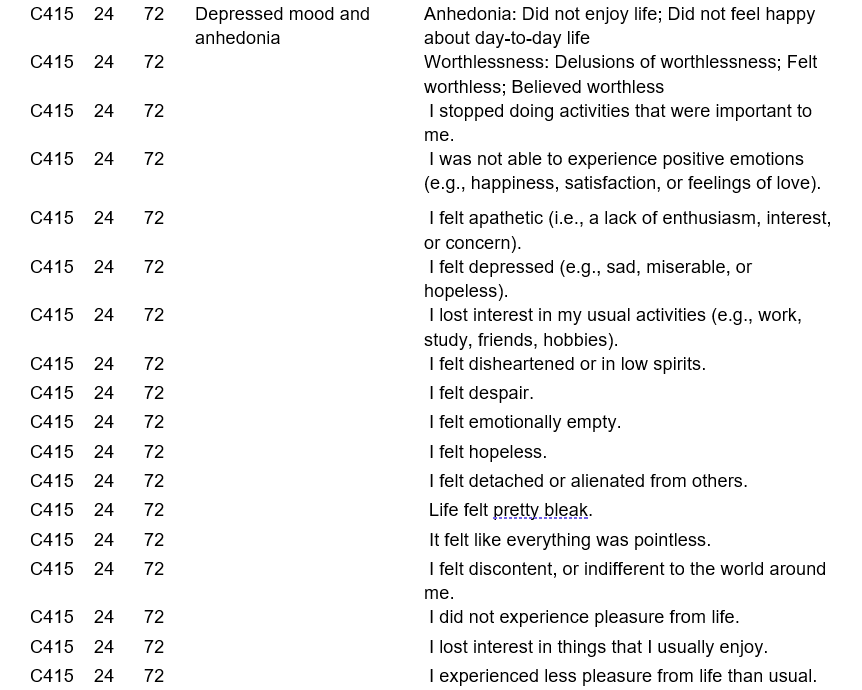

Here is the depressed mood and anhedonia cluster:

Here are the self-derogation, suicidality, and guilt/shame proneness clusters:

There is something statistically distinctive about the clusters labeled as ‘depressed mood and anhedonia,’ ‘self-derogation,’ ‘suicidality,’ ‘guilt/shame proneness,’ ‘morning depression,’ ‘emotional lability,’ etc., but there is nothing statistically distinctive about the combination of 9 symptoms that we recognize as diagnostic criteria for depression:

So, what is going on here?

Obviously, people present with symptoms associated with major depression, and they report these symptoms if they are asked about them. That isn’t in doubt. What is in doubt is whether there is anything statistically special about this symptom combination.

All syndromes in the ‘Distress’ subfactor are correlated with each other, so people would present with various combinations of the syndromes, with some inclusion of symptoms/syndromes from other subfactors and spectra (since they are all correlated at a higher level).

Ms. Jones may experience:

Depressed mood and anhedonia

Morning depression

Self-derogation

Suicidality

Guilt/Shame

Early sleep and awakening

Mr. Jamal may experience:

Depressed mood and anhedonia

Irritability

Emotional lability

Psychomotor agitation

Insomnia

Anxiousness

Ms. Freeman may experience:

Depressed mood and anhedonia

General cognitive difficulties

Distractibility

Psychomotor impairment

Suspiciousness

Psychological panic

Guilt/Shame

All three meet MDD symptom criteria, but they all show varying combinations of more fundamental (statistically homogenous) syndromic clusters.

MDD indexes a varying and heterogenous subset of symptoms/syndromes, and what is common about these varying subsets is that depressed mood and/or anhedonia are prominent aspects of the presentation. In a similar manner, GAD indexes a varying and heterogenous subset of symptoms/syndromes, and what is common about these varying subsets is that pervasive anxiety is a prominent aspect of the presentation. And PTSD indexes a varying and heterogenous subset of symptoms/syndromes, and what is common about these varying subsets is that traumatic intrusions and avoidance are prominent aspects of the presentation. The subsets that constitute MDD, GAD, and PTSD all overlap, which is why these heterogenous categories dissolve when statistical homogeneity is sought. (This is also one reason why the reliability for MDD and GAD was so low in DSM-5 field trials.)

You can see in the figure below how MDD dissolves into homogenous elements that map onto ‘Distress,’ ‘Neurocognitive Impairment,’ ‘Dysregulated Sleep,’ and ‘Dysregulated Eating.’

Ken Kendler notes in his historical review of depression symptoms and the DSM:

“… the author examines how well DSM-5 symptomatic criteria for major depression capture the descriptions of clinical depression in the post-Kraepelin Western psychiatric tradition as described in textbooks published between 1900 and 1960. Eighteen symptoms and signs of depression were described, 10 of which are covered by the DSM criteria for major depression or melancholia. For two symptoms (mood and cognitive content), DSM criteria are considerably narrower than those described in the textbooks. Five symptoms and signs (changes in volition/motivation, slowing of speech, anxiety, other physical symptoms, and depersonalization/derealization) are not present in the DSM criteria. Compared with the DSM criteria, these authors gave greater emphasis to cognitive, physical, and psychomotor changes, and less to neurovegetative symptoms. These results suggest that important features of major depression are not captured by DSM criteria. This is unproblematic as long as DSM criteria are understood to index rather than constitute psychiatric disorders. However, since DSM-III, our field has moved toward a reification of DSM that implicitly assumes that psychiatric disorders are actually just the DSM criteria. That is, we have taken an index of something for the thing itself.”

DSM criteria for MDD are an index, but what is the thing itself? If Forbes et al. are correct, the thing itself isn’t a fixed, stable entity but consists of variable and heterogenous subsets of internalizing and neurocognitive symptoms. And each time we use MDD as an index, we index something different. (Different from but overlapping with other instances.)

DSM criteria for MDD are an index, but what is the thing itself? If Forbes et al. are correct, the thing itself isn’t a fixed, stable entity but consists of variable and heterogeneous subsets of internalizing and neurocognitive symptoms. And each time we use MDD as an index, we index something different.

There are some important limitations to note with regards to the Forbes et al. survey. It relies only on self-reported symptoms, and features requiring clinician observation are missing; symptoms are decontextualized (e.g., insomnia due to substance withdrawal isn’t differentiated from insomnia due to anxiety); all symptoms were assessed using a 12-month time scale, even though different symptom patterns exist at different time scales.

Forbes et al. themselves note,

“It will also be essential to understand which aspects of these results—particularly the fine-grained levels of the structure—are robust to other approaches to measurement (i.e., using alternative measures, time frames, multi-method or multi-informant approaches, as well as within-person assessment) and across intersectional conceptualizations of identity (e.g., in a variety of sociodemographic and culturally and linguistically diverse samples).”

See also:

I wonder how many psychiatrists agree with this statement by the study authors: "Since DSM-III, our field has moved toward a reification of DSM that implicitly assumes that psychiatric disorders are actually just the DSM criteria." I have read articles by psychiatrists who use DSM criteria for billing and administrative purposes but consider them to be oversimplifications of complex conditions.

"...the thing itself isn’t a fixed, stable entity but consists of variable and heterogeneous subsets of internalizing and neurocognitive symptoms..."

Borsboom's claim: "Recent work has put forward the hypothesis that we cannot find central disease mechanisms for mental disorders because no such mechanisms exist" in Borsboom D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 16(1), 5–13.

Translation: there are just dynamic interactions between an agent's metaphysical presuppositions relative to the population at large, the neural state of that particular body, and the contexts they find themselves in.

Conclusion: there is no such thing as a substantial form of mental disorder that can be eternally defined from a nomothetic paradigm.