Why Did Evolution Leave Us Vulnerable to Mental Disorders? A Q&A with Randolph Nesse

“Individuals with disorders often have advantages, but that does not make the disorder an adaptation.”

Randolph M. Nesse is a founder of the fields of evolutionary medicine and evolutionary psychiatry. During his 40-year career as a psychiatrist on the faculty at the University of Michigan, he helped to develop one of the first specialty clinics for anxiety disorders, directed the training programs, taught scores of residents and fellows, conducted research on neuroendocrine responses to anxiety, and collaborated with colleagues on the main campus to organize the Evolution and Human Behavior Program and the Human Behavior and Evolution Society. In the early 1990s, he collaborated with the biologist George Williams to write articles and a book that inspired the growth of the field of evolutionary medicine. In 2014 he moved to Arizona State University as the Founding Director of the Center for Evolution and Medicine, a position that made it possible to create the International Society for Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association, an elected fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a member of the American College of Psychiatrists.

Aftab: I have to confess, I was rather skeptical of evolutionary psychiatry until I read your book “Good Reasons for Bad Feelings” a few years ago, and I felt regret that I had not previously engaged with such a rich way of thinking about medical and psychiatric problems. My skepticism had been based on my general impressions of evolutionary psychology as a shaky scientific discipline full of just-so stories (an impression that a lot of people share), and it took me a while to appreciate the value of considering evolutionary explanations of psychiatric traits in addition to proximate explanations of their mechanisms. “Good Reasons for Bad Feelings” is a great resource for general readers as well as professionals. For academic clinicians, I’ll additionally recommend your 2023 World Psychiatry article, “Evolutionary psychiatry: foundations, progress and challenges” as a good introductory overview. Your website also has a lot of resources, with links to relevant articles, book chapters, podcasts, and blog posts.

Let’s start by talking about how evolutionary thinking transformed your own understanding of the nature of mental disorders and their treatment as a psychiatrist.

Nesse: Thanks for the chance to discuss evolutionary psychiatry, Awais. My career has focused on a single question: Why did natural selection leave bodies so vulnerable to disease? It started with an undergraduate project about why aging exists and continued with curiosity aroused but left unsatisfied by what I observed in medical school. Why did natural selection leave us with an appendix and a narrow birth canal? Why do our defenses against infection and cancer fail so often?

As an assistant professor of psychiatry in the early 1980s, I was frustrated by the battles between the psychoanalysts and the reductionist biologists who were replacing them. So many smart people arguing to no purpose made it clear that something was missing. There had to be some solid scientific foundation, some common framework for all efforts to understand and treat the mental disorders that are so horrifyingly severe and common.

I found my way to a group of biologists at the Museum of Natural History who studied behavior, led by the evolutionary biologist Richard Alexander. They welcomed me saying, “As a psychiatrist, of course you must have studied the evolution of animal behavior in depth.” Uh, no, not really. They then pointed out that a full biological explanation requires describing both the mechanism and also how it was shaped by natural selection. What a huge shock to realize that my apparently superb education had ignored half of biology! Finally, they pointed out that my brilliant idea that selection shaped senescence so that species could evolve faster was not only wrong, it was inconsistent with modern evolutionary theory; individuals who die sooner pass on fewer genes, so even if senescence did benefit the species, that could not explain the persistence.

They told me to read the 1957 article by George Williams about senescence. It transformed my thinking and my career. He explained aging as a product of genes that are selected for because they give benefits early in life when selection is strong, even though those same genes cause aging and death later in life. I spent a summer analyzing data on the survival of animals in the wild for my publications that supported his theory. All of that aroused a larger question. If aging has an evolutionary explanation, what about schizophrenia, OCD, depression, and eating disorders?

My 1984 article on evolutionary psychiatry preceded work on evolutionary medicine. It includes many ideas that continue to resonate today, but I quickly realized that to really understand the origins of mental disorders, and to convince others about the value of evolutionary biology in psychiatry, I would first have to understand why natural selection left us vulnerable to diseases in general. It was my great privilege to work with the great biologist George Williams to write articles and a book that got evolutionary medicine going. But it took me another decade to realize that the confusion that swirls around psychiatry really does result mostly because it lacks the evolutionary foundation that the rest of medicine relies on. And it took another decade after that to see that evolution can be profoundly useful for understanding emotional disorders and the motivational structure of individual lives. I think we are halfway to a solid foundation for understanding why humans are so vulnerable to so many mental disorders, but only halfway.

Aftab: Something I really like about your approach to evolutionary psychiatry is that you repeatedly emphasize the following point:

“… viewing true diseases as if they were adaptations is [a] serious error that is common in evolutionary psychiatry. It is tempting to try to explain schizophrenia, anorexia nervosa or autism by proposing ways that they might offer advantages, but such hypotheses are almost always wrong. Diseases are not adaptations shaped by natural selection. They are not universal traits. They harm fitness. Trying to explain diseases as if they were somehow useful gives rise to a conceptual fog, which will be dispelled, not by global debates about adaptationism, but by systematically considering specific hypotheses in the light of rigorous evolutionary theory.” (World Psychiatry, 2023)

In contrast, on social media, it is common to see assertions along the lines of “mental disorders persist because they offer evolutionary advantages” or “they came with useful evolutionary trade-offs.” I find it troublesome because it has burgeoned into an evolutionary variety of Szaszian thinking: mental disorders aren’t disorders because they are actually evolutionary adaptations. I’m sure you also find it concerning since it is a misunderstanding and misuse of an intellectual endeavor you’ve devoted your life to.

I have two questions for you in this regard. One, the point you are making about treating psychiatric diseases as if they offer evolutionary advantage… is this contentious or controversial in any way in the evolutionary psychiatry world?

Second, those who define diseases/disorders in evolutionary terms (e.g. requiring ‘failure of an evolved mechanism’ as a criterion) may say that the point is merely tautological. Of course diseases are not adaptations precisely because that follows from the definition of disease. And some of these folks may say that they actually disagree that schizophrenia, anorexia nervosa or autism are diseases to begin with because it has not been demonstrated to their satisfaction that dysfunctions of evolved mechanisms exist in these cases. The impression I get from your writings is that you think there are ways for us to confidently say that something is a disease based on clinical features and the impact on fitness. Is that so? How would you respond to people who don’t think that schizophrenia, anorexia nervosa, or autism are diseases?

Nesse: I was dismayed and outraged in the 1980s by the politicized debates Gould and Lewontin’s Spandrels of San Marco article generated. Their rhetorical masterpiece set back the evolutionary study of adaptation and behavior by a decade, leaving many people thinking, even now, that all studies of adaptation are “just-so-stories.”

However, three decades of teaching evolutionary medicine has forced me to recognize the depths of the problem. I start each semester with examples of wild adaptationist wrong explanations, saying, “don't do that!” And at the end of every semester, students turn in term papers on “How natural selection shaped schizophrenia” or “The selective advantages of anorexia nervosa.” Humans have a deep cognitive tendency to categorize things by their function, and to attribute functions to most everything. Despite my best efforts, attempts to explain disorders as if they are adaptations is the biggest problem for evolutionary psychiatry. Such ideas are fascinating because they are paradoxical. Melancholia might be useful! Anorexia may give advantages! Schizophrenics may have been shamans who got special respect and mating opportunities! Social media spread such surprising ideas like transmissible diseases, generating clicks and much more attention than more sober possibilities like genetic drift, epistasis, tradeoffs, and the limitations of natural selection. The leaders in evolutionary psychiatry are well aware of the challenge. I have an article in the works that offers a rubric for assessing hypotheses, one that emphasizes beginner’s mistakes and that several explanations may all contribute to an explanation for vulnerability to a disorder.

It is worth noting that similar mistakes are pervasive in “biological” psychiatry. The idea that depression results from a deficiency in serotonin persists even though it never made sense in evolutionary terms and was long ago falsified by data. The simplistic idea that excess dopamine causes schizophrenia generated decades of studies. And the search for specific genes and specific brain loci that cause specific disorders continues despite data (generated by hundreds of millions of research dollars) showing that such ideas are vastly simplistic. The quest is worthwhile. We should all still hope that specific causes are found for devastating conditions like autism, schizophrenia and OCD, but a mountain of evidence suggests that such hopes are unlikely to succeed. If evolutionary studies received one tenth of the resources devoted to the search for specific mechanisms we would now have a solid understanding of the evolutionary origins and adaptive significance of those mechanisms, the missing foundation for a truly biological psychiatry.

We humans are simple thinkers, carving continuous phenomena into discrete categories and attributing simple explanations to each one, explanations we continue to embrace and defend even in the face of contrary evidence. The messy reality of organic complexity is repugnant, but recognizing it offers our best hope for real understanding of mental disorders.

In the meanwhile, another mistake is as pervasive as attempting to explain disorders as if they are advantages. Failing to recognize that anxiety and low mood are useful responses shaped by natural selection remains prevalent, crippling attempts to understand anxiety and mood disorders.

As for defining diseases, I had a good run at that question in a 2001 article (On the difficulty of defining disease: A Darwinian perspective. Medical Health Care and Philosophy) that has often been reprinted, translated, and cited. It does not solve the problem, but it explains why it has been so intractable. The last paragraph in that article (in the indented quote below) provides a nice summary that presaged my current preoccupation with tacit creationism and the useless debates that arise from viewing the body as if it is a product of design even without reference to a designer. The structure of organically complex systems is vastly different from anything an engineer would create. It is messy in ways that make it hard to describe. This is also the source of the problem for psychiatric nosology, as Dan Stein and I have argued in an article about how an evolutionary perspective can make diagnosis in psychiatry more like that in the rest of medicine.

“So, what is disease? It seems to me that philosophers have answered the question relatively well, given the constraints of trying to provide a definition in words. Yes, there is disagreement, but for the reasons mentioned, no single definition will serve all the functions demanded of it. An individual has a disease when a bodily mechanism is defective, damaged, or incapable of performing its function. The continuing debates about the definition of disease arise partly from the hope that a logical definition can be found that conforms to common usage based on prototypes, partly from attempts to seek the essence of disease without reference to all the complexity of the mechanisms of the body and their origins and functions, and partly from the political and moral implications of labeling a condition a disease. We will undoubtedly see if further pursuit of these debates will, or will not, deepen our understanding of what disease is.” (Nesse, 2001)

Twenty-five years later, debates continue, I think for the reasons described in the article.

Aftab: You write in the World Psychiatry article, “Explanations for mental disorders based on benefits to a group should be viewed with suspicion.” And “attempts to explain a trait that harms inclusive fitness by benefits to a group are inconsistent with evolutionary theory.” Can you elaborate on the significance of what you are saying here?

Nesse: More than half a century ago, the scientific understanding of social behavior was transformed by the recognition that tendencies for an individual to make sacrifices that benefit the group are shaped not by benefits to the group, but by benefits to kin who have genes in common with the individual. This advance has not made it to psychiatry. Many psychiatrists still imagine that traits like guilt or prosocial behavior are shaped by benefits to groups. Worse yet, some who write about evolution and psychiatry try to argue that benefits to groups can explain tendencies to anorexia nervosa, depression or even suicide. There is no better illustration of the gulf between psychiatry and the basic science of behavioral biology.

The misunderstanding is understandable. Until the 1960s most biologists thought that natural selection shaped social traits because of their benefits to groups, species and even entire ecosystems. The illusion is fostered by the ready observation of costly behaviors that benefit groups; how else could such sacrifices be explained? It is augmented by our emotions; we feel that it is noble and good to sacrifice for our friends and groups, and bad and selfish to pursue self-interest at their expense. So the misunderstanding persists. The solution is to recognize that selfish genes make people, and individuals in some other species, generous especially towards kin. That runs the risk of fostering the even more serious false belief that selfishness is somehow natural, a socially corrosive belief that has become more common in recent decades.

Kin selection and mutualisms are the most powerful forces shaping social behavior but their inability to fully explain capacities for morality, guilt and extreme prosocial behavior has spurred two generations of work to find the explanations. There are many. Mutualisms, trading favors, and reputation are important and cultural group selection is real. But I and others have argued that selective association is an important neglected explanation. Individuals who are preferred as social partners get better partners with accompanying big advantages, so natural selection has shaped us to care enormously about what others think about us and to display prosocial traits, such as contributing generously to our groups. This is the foundation for understanding social anxiety, self-esteem, psychotherapeutic relationships, and more. But this fundamental principle is missing from psychiatry.

Aftab: There is a really important point you make in the article that adaptations involve trade-offs and individuals with values away from the population mean can be at a net disadvantage while having some advantages: “those advantages can increase disease vulnerability by spreading the trait distribution, but they do not make the disease an adaptation.” Is there a psychiatric example that illustrates this?

Nesse: Individuals with disorders often have advantages, but that does not make the disorder an adaptation. Instead, most traits involve tradeoffs, and individuals with values away from the mean of a trait will have advantages as well as net disadvantages. People with low blood pressure have less atherosclerosis but more fainting. People who don’t sweat as much as others are less likely to get dehydrated but more likely to experience heat stroke. People with autistic traits systematize well. Some people with schizophrenia seem to have uncanny empathy. People with OCD avoid contagion and people with bipolar disorder have many sex partners. Such advantages suggest to the unwary that perhaps such conditions themselves are favored by natural selection. But such advantages don’t begin to outweigh the big disadvantages. Serious mental disorders are selected against. But looking for advantages and how they are related to tradeoffs can be crucial for understanding the evolutionary origins of a disorder.

Aftab:

Table 1. Evolutionary explanations for disease vulnerability

1. Individual variations resulting from mutations and developmental instability

2. Species-wide vulnerabilities resulting from genetic drift and path dependence

3. Parasites that evolve much faster than hosts

4. Mismatch between bodies and novel environments

5. Trade-offs that increase the fitness of individuals

6. Traits that increase gene transmission at a cost to robustness

7. Defensive responses that are vulnerable to excess expression and dysregulation

(Nesse, 2023)This table from your World Psychiatry article is a great summary list of evolutionary explanations for disease vulnerability that I am sharing for the benefit of all. One thing I want to point out here for readers is the idea that there can be a misalignment between optimization of gene transmission and optimization of health. Traits that increase reproduction are selected for even if they reduce health and well-being. In other words, our notion of health cannot be reduced to some notion of “evolutionary design” and just because a mechanism is doing what it has evolved to do doesn’t mean that it is good for our well-being, and we can have good clinical reasons to intervene on it. Would you like to add anything to this?

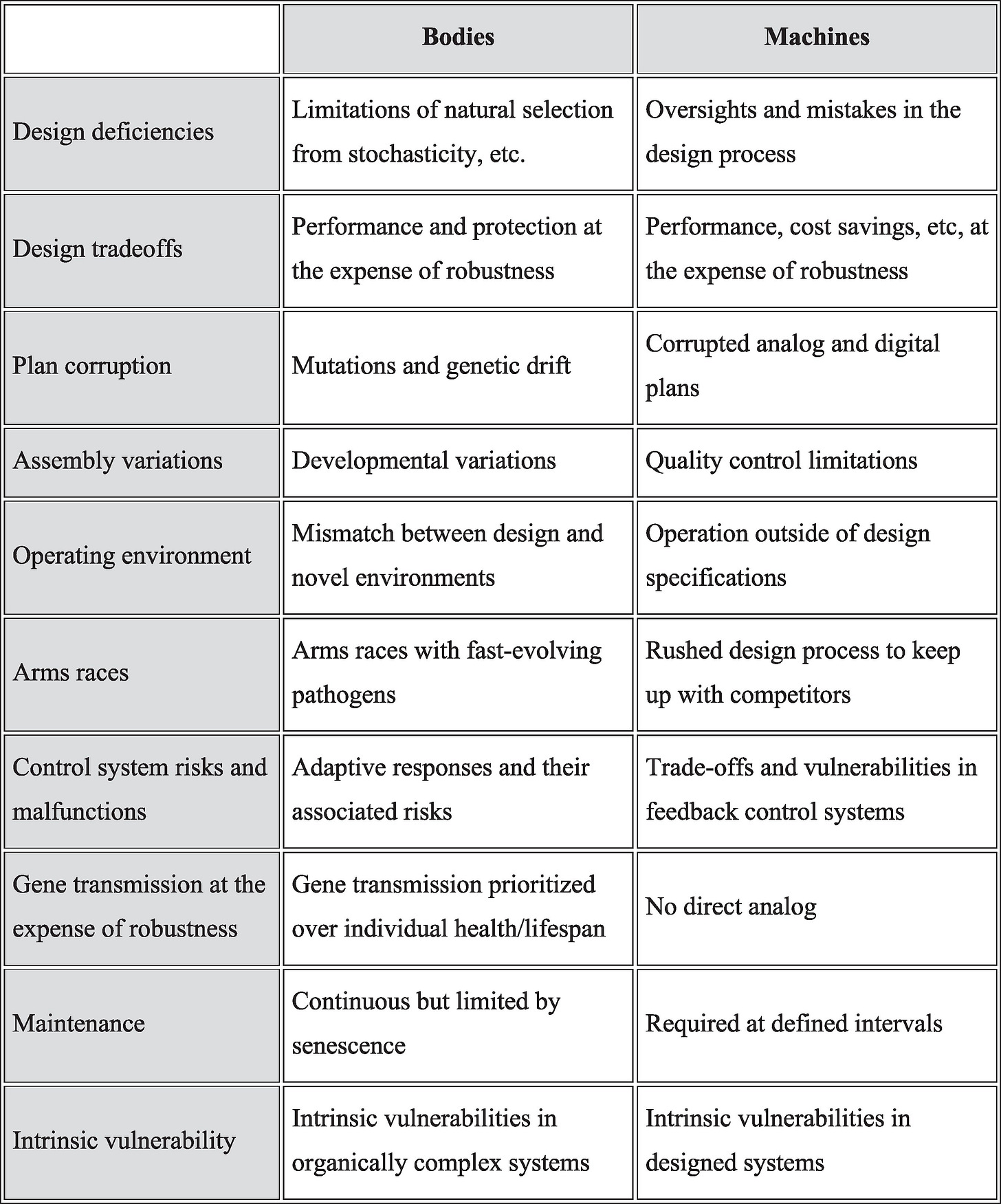

Nesse: What a good and timely question! The number of categories has expanded to ten in my article with Guru Madhavan and Jay Labov, “Explanations for failure in designed and evolved systems” that was just published in PNAS Nexus. I will paste the table below for those who might be interested.

Also, you put your finger on the big difference between the reasons for failures in bodies compared to machines! Natural selection maximizes gene transmission, often at the expense of health, happiness, and longevity. That is why people spend so much time and energy thinking about sex and competing for mates in ways that are expensive and dangerous… and that land them in mental health clinics.

Also note that the category of defenses is not really a reason for vulnerability, it refers to useful responses like fever, pain and vomiting... and anxiety and low mood... that are often incorrectly viewed as diseases. But control systems for defenses are prone to failure (for several of the other reasons) resulting in vast misery from chronic pain, anxiety disorders, and depression.

Aftab: You talk about how anxiety and low mood are adaptive responses that are aversive for good reasons, and thanks to the “smoke detector principle,” they are by design prone to false positives. “Like physical pain, ordinary low mood is a potentially useful response to a bad situation. Both can be expressed excessively or when they are not needed, resulting in the vast suffering.” You also discuss how “self-adjusting control systems are intrinsically vulnerable to vicious positive feedback cycles.” Panic attacks, for example, escalate into panic disorder due to positive feedback loops.

Now it seems to me that anytime we are dealing with an emotional regulation system stuck in a self-sustaining feedback loop, this would constitute abnormal regulation. Vicious cycles are not adaptive; adaptive systems have a vulnerability to fall into vicious cycles. This means that when we are dealing with clinical cases of anxiety, panic, or depression that demonstrate features of detrimental self-reinforcement, we are no longer in the “excess expression of an adaptive defense” territory but rather “dysregulation of a control system” (and therefore genuinely disordered) territory. Am I getting this right?

Nesse: A goal of the PNAS Nexus article is to encourage researchers to make better use of methods engineers have developed for analyzing control systems. Most mental disorders, and most medical disorders in general, involve control system malfunctions. Control systems are intrinsically vulnerable because the benefits of high gain come at the cost of lower stability. Natural selection, like human engineers, sets the parameters of such systems to optimize the tradeoffs, even though that makes some failures inevitable. Also, positive feedback loops are essential to the optimal functioning of most systems, but they are vulnerable to going into runaway escalations.

I think that is what happens in manic episodes. After some grand success most of us experience an apparently unaccountable let down for a few days; when that inhibition is missing, success can generate enthusiasm and effort that creates yet more apparent success in a frenzy that ends only when a mechanism shuts down the system, crashing it into depression. The sticking points at both extremes are recognized by engineers as typical for a system in which the gain is set too high, but most psychiatric research continues to look for some specific gene or neurotransmitter or brain locus.

Panic disorder is my clinical specialty. It took a decade after I recognized it as an adaptive emergency reaction before I recognized how fear of attacks led to monitoring for any hint that an attack is beginning, so a bit of high heart rate or shortness of breath creates more anxiety, with more arousal that spirals into a full-blown panic attack. There is a world of opportunity for investigating mental disorders as failures of control systems.

Aftab: One of the things that has stayed with me the most from your writings is your discussion of how being trapped in the pursuit of an unreachable goal is “the perfect depressogenic situation.” I do see cases of depression in the clinic where the onset of depression seems linked to an unreachable goal, however, most of the time it is not enough for me to point out that relationship for the person to start making changes. Most patients I see in such a scenario tend to be so overwhelmed and sapped that their depression has to be first treated with antidepressants and/or psychotherapy for them to get to a point where they can begin to disengage from the unreachable goal. What has your clinical experience been?

Nesse: Only about a third of the depressed patients I evaluated were trapped in the pursuit of an unreachable goal, but asking patients if they are committed to doing something that is unlikely to succeed often reveals the source of anxiety and depression better that asking about stress or life events. Losses cause sadness or grief that fades with time. But when people persist in failing efforts, the normal low mood system that reallocates effort elsewhere can’t achieve its aim, so ordinary bad feelings escalate into full blown depression. Many people get trapped in useless efforts to do something vastly important. Getting a child to stop using drugs. Stopping drinking. Getting a spouse to stop drinking. Getting a spouse to have sex. Getting away from an abusive boss. Getting into medical school or the NFL. Getting control of cancer or chronic pain.

Understanding the motivational structure of a person's life is crucial, but it takes time and empathy, and it does not lead to quick solutions. People solve solvable problems, but social traps make some problems insolvable. The first therapeutic stance is to understand why the person is trapped. There are always good reasons. Getting out of the trap is painful or financially or reputationally costly. Finding alternative strategies is the key, but it is rarely easy. Medications, and psychotherapy can help a person develop the sense of agency needed to do difficult things that change the situation. Or, more usually, change how they think about the situation.

Aftab: Philosophical critics of evolutionary approaches to psychiatry and psychology have brought up what has been described as the “matching problem.” Subrena Smith articulated it in the case of evolutionary psychology, and in a 2024 paper, Hane Maung applied it to evolutionary psychiatry. The basic idea is that certain conditions need to be met in order for evolutionary psychiatry hypotheses to be empirically testable. Certain assumptions must be true about the psychological mechanisms that our evolutionary ancestors possessed, and critics say that we lack the methodological resources to demonstrate the truth of those assumptions since psychological mechanisms don’t leave a fossil record, making evolutionary psychiatry hypotheses “indefinitely underdetermined by data.” What are your thoughts on the matching problem?

Nesse: That line of thinking is very abstract. I fully agree that it can be devilishly hard to frame and test hypotheses about why natural selection has left us vulnerable to mental disorders, and to diseases in general. But the categories are not simple and some authors seem to think a time machine is necessary, which would eliminate geology and cosmology as well as evolutionary studies. I wish philosophers who want to help would first learn behavioral ecology and then look at articles that provide guidance on how to frame and test hypotheses about disease vulnerability. [Nesse, R. M. (2011). Ten questions for evolutionary studies of disease vulnerability]

Aftab: What would you consider to be the most scientifically successful example of a hypothesis based on the evolutionary psychiatry approach?

Nesse: To pick just one, panic attacks are preprogrammed emergency responses that often go off when they are not needed because of the smoke detector principle. And panic disorder develops when the control system goes into a positive feedback loop in which fear of an attack causes anxiety that causes symptoms like increased heart rate or rapid breathing, which convinces the person that an attack is coming, and sure enough, it usually does, by simple positive feedback.

But the greatest contribution of evolutionary psychiatry is not a few hypotheses that can be rated on how well they are supported. More valuable is the framework it provides for asking new questions about the origins of vulnerability to mental disorders, and new ways to understand those disorders. Some are simply products of defective genes. Many result when deviations from the population mean give an individual advantages with net disadvantages. Emotions need to be understood not only by brain loci, neurotransmitters, or even evolutionary functions, they need to also be understood by analysis of the adaptive challenges in the situations that shaped them. And their disorders need to be understood in control system terms. And all of that requires a detailed understanding of the motivational structure of an individual’s life. Evolutionary psychiatry offers a missing foundation for making sense of mental disorders in general, and for understanding the problems experienced by specific suffering individuals.

The field of evolutionary psychiatry is growing fast, thanks especially to the efforts of Riadh Abed and Paul St John-Smith and the Evolutionary Psychiatry Special Interest Group they have organized for the Royal College of Psychiatry. More information is available here. The World Psychiatry Association also has a Section on Evolutionary Psychiatry.

Aftab: Thank you! And for interested readers, I’d also point out that the Evolutionary Psychiatry SIG has a presence on Substack:

.This post is part of a series featuring interviews and discussions intended to foster a re-examination of philosophical and scientific debates in the psy-sciences. See prior interviews here.

Psychiatry at the Margins is a reader-supported publication. Subscribe here.

See also:

"We should all still hope that specific causes are found for devastating conditions like autism, schizophrenia and OCD, but a mountain of evidence suggests that such hopes are unlikely to succeed."

I get that Nesse makes some important points re evolution etc, but DAMN does he make sweeping claims about "devastating conditions".