Brain Metaphors Beyond Brain Mythologies

A commentary on Kendler's history of metaphorical brain talk in psychiatry

I’ve yet to read an article by Kenneth Kendler that didn’t leave me with something new or unexpectedly useful, whether it is a new insight, a sharpened question, or a clearer way of thinking. The man just doesn’t miss. Earlier this year, he published “A history of metaphorical brain talk in psychiatry” in Molecular Psychiatry, which is a piece tracing the history, meaning, and significance of “metaphorical brain talk” in psychiatry.

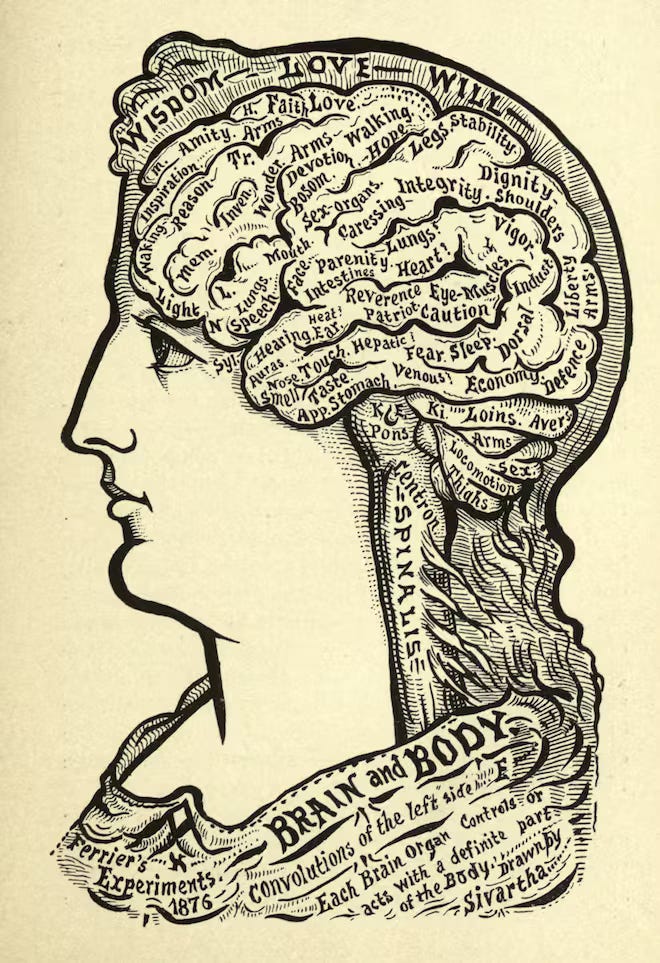

Kendler starts off by offering historical examples from 18th- and 19th-century asylum psychiatrists who tried to explain madness using vague and metaphorical brain concepts. Common tropes include “inequality of excitement,” “morbid action of vesicular neurine,” and “disordered arrangement of nerve tissue.” He notes that these could easily have been stated in mentalistic language but were instead recast in pseudo-biological terms.

The rise of the first biological revolution in psychiatry was driven by Wilhelm Griesinger and his disciples (e.g., Meynert, Westphal, Wernicke). Griesinger emphasized psychiatry as brain-based medicine and inspired generations to search for neuropathological causes of mental illness via anatomical and physiological investigations. Despite initial enthusiasm, this research produced little insight into classical psychiatric disorders. Instead, it gave rise to increasingly elaborate and metaphorical brain-based theories.

Critics emerged by the late 19th century, including a young Emil Kraepelin. In his inaugural lecture at Dorpat (1887), Kraepelin lambasted the speculative excesses of biological psychiatry, particularly the theories of Theodor Meynert. He accused Meynert of overreaching with anatomical claims unsupported by empirical data and likened his theorizing to “airily-constructed houses” lacking solid foundations. Kraepelin objected to the speculative use of reductionist neuroscience to explain complex mental phenomena.

Kendler shares historical accounts that describe Meynert’s theories as extravagant fusions of anatomy and fantasy. Meynert imagined nerve cells endowed with a “soul,” proposed fantastical fiber-pathways as correlates of mental processes, and explained mood disturbances through humoral-style theories about blood flow. His student, Auguste Forel, called his constructions “fantastical,” and others noted his success lay in crafting material images of the brain that resonated with metaphorical ideas of the mind.

Adolf Meyer and Karl Jaspers both criticized such anatomical explanations lacking scientific basis as “brain mythology.” Their quotes are worth sharing:

“Instead of analyzing the facts in an unbiased way and using the great extension of our experience with mental efforts to get square with things … they pass at once to a one-sided consideration of the extra-psychological components of the situation, abandon the ground of controllable observation, translate what they see into a jargon of wholly uncontrollable brain-mythology, and all that with the conviction that this is the only admissible and scientific way.” (Meyer, 1907 – quoted by Kendler)

“The still widespread “somatic prejudice” is: everything mental cannot be examined as such, it is merely subjective. If it is to be discussed scientifically, it must be presented anatomically, physically, as a physical function; for this it is better to have a preliminary anatomical construction, which is considered heuristic, than a direct psychological investigation. Such anatomical constructions are quite fantastic (Meynert…) and are rightly called “brain mythologies.” Things that have no connection to one another, such as cortical cells and memory images, brain fibers and psychological associations, are brought together. There is also no basis for these mythologies insofar as not a single specific brain process is known that could be assigned to a specific mental process as a direct parallel phenomenon.” (Jaspers, 1913; Kendler translation).

Kendler draws 4 conclusions from his study of this history:

“this trend has continued to the present day in metaphors such as the “broken brain” and the use of simplistic and empirically poorly supported explanations of psychiatric illness, such as depression being “due to an imbalance of serotonin in the brain.””

“our language stems from the tension in our profession that seeks to be a part of medicine yet declares our main focus as treatment of the mental. We feel more comfortable with the reductionist approach of brain metaphors, which, even though at times self-deceptive, reinforce our commitment to and membership in a brain-based medical specialty.”

“metaphorical brain talk can also be seen as the “promissory note” of our profession, a pledge that the day will come when we can indeed explain accurately to ourselves and to our patients the brain basis of the psychiatric disorders from which they suffer.”

“Finally, moving away from metaphorical brain talk would reflect an increasing maturity of both the research and clinical aspects of our profession.”

My qualms with Kendler’s definition of “metaphorical brain talk”

Kendler defines “metaphorical brain talk” at two points. The abstract defines it as “rephrasing descriptions of mental processes in unconfirmed brain metaphors.”

The article offers an expanded definition:

“… a concept I call “metaphorical brain talk,” defined as describing the disturbed mental processes in psychiatric illness in terms of brain function in ways that appear to be explanatory but actually have little to no explanatory power.”

My main concern with this definition is that many of the historical cases Kendler shares are not technically “descriptions” or “rephrasings” but rather

statements about the relationship between the categories of “mental illness” and “brain disease”

hypotheses about the brain causes of mental illnesses, which are vague, empty, or empirically unsupported

assumptions that (specific) mental illnesses will turn out to be brain disease entities (similar to neurological and infectious diseases)

These assertions are also problematic for a variety of reasons, but I just want to point out that they don’t fit the definition very well.

Discussing the asylum-era psychiatry literature, Kendler says, “Nearly all these observations could have been stated in mental language, but were not.” However, if you read the actual quotes in the article, the way I see it, the problem is not that observations were stated in neurological terms, but rather that brain hypotheses were invoked casually and freely without consideration of the theoretical rigor and empirical evidence such hypotheses demand.

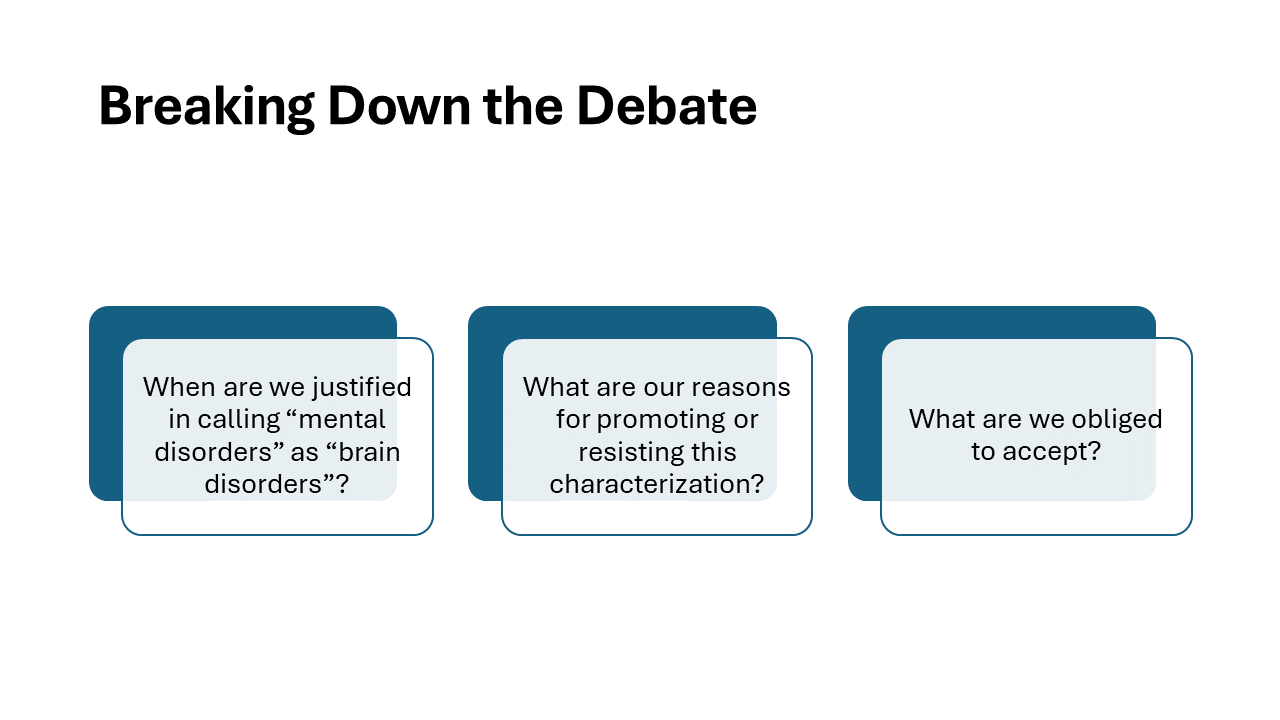

On the general relationship between “mental disorders” and “brain disorders”

I have previously written and spoken on the question of when we are justified in characterizing mental disorders as brain disorders, so I won’t belabor the points. See my Philosophical Psychology article “Mental disorders in entangled brains,” which is a commentary on Anneli Jefferson’s work, and my prior substack post, “Mental Disorders Both Are and Are Not Brain Diseases,” which was prompted by another article by Kendler.

There is a broad metaphysical sense in which mental disorders are brain disorders. Since psychiatric disorders are instantiated in the brain, they are by inference brain disorders. Saying so is uninformative and vacuous. As Jefferson points out, it is simply an expression of one’s commitment to naturalism.

Then there is a narrow view in which mental disorders are brain disorders if they are expressions of a brain process that is identifiable as dysfunctional in an individual without reference to the psychological symptoms and where the dysfunction causally precedes mental symptoms. Psychiatric disorders, except those recognized as being secondary to neurological disorders, are not brain disorders in this strict sense.

In between these two positions is a broad and ambiguous zone where the brain processes associated with psychiatric disorders can be empirically identified with varying degrees of coherence, tractability, explanatory power, and clinical utility. On this spectrum, we can set different empirical thresholds for when we are justified in calling a mental disorder a brain disorder. For instance, I have previously proposed that we can be justified in calling a psychological dysfunction a brain dysfunction if there are substantial, reliable, and systematic brain differences associated with the psychological dysfunction.1

Here’s how I summarized things in a talk for the neuroscience and philosophy salon:

Mind is embodied: psychiatric conditions are instantiated by (or mediated by, or emerge from) brain and bodily processes. However, these bodily processes cannot necessarily be characterized as dysfunctional, except in the indirect sense that they mediate psychological dysfunction.

We are obliged to accept that mechanisms and processes involved in psychiatric illnesses do occur in the brain (but not exclusively in the brain); the embodiment of mind necessitates that this will be so. However, these pathways will relate to the psychiatric phenomenon in question with varying degrees of explanatory coherence, ranging from utterly incoherent (like marital status) to highly coherent (like aphasias).

There is a heavily qualified empirical sense—and not just an empty metaphysical sense—in which mental disorders can be demonstrated to be brain disorders provided certain empirical requirements are met. There are reasons for us to accept that characterization and reasons for us to resist it. These reasons differ based on disciplinary agendas.

Although we are obliged to accept the embodiedness of mind and the existence of brain mechanisms of psychopathology, we have no obligation to accept “mental disorders are brain disorders” as the best or the most appropriate characterization given their complex, multi-level causality.

Kendler believes in brain dysfunctions?

During his discussion, Kendler provides an important qualification:

“To be clear, my criticism of metaphorical psychiatric brain talk is not a critique of the rigorous scientific reductive agenda in modern psychiatric research that seeks to understand the etiology of psychiatric illness. Indeed, I have spent most of my career in the study of psychiatric genetics, clearly, at least in part, a reductive research project. My concern is rather the degree to which the profession of psychiatry, over its long history, has impoverished its conceptual foundations by a strong brain-focused bias in how we talk, and, more importantly, think about mental disorders. We are at risk of underappreciating efforts to understand the first-person experiences of our patients. If our reductionist neuroscience efforts are to succeed, we will have to be able to link our scientific explanations with incisive understanding of the states of mental illness we treat. We could then provide our patients not with empty, metaphorical brain-talk, but a real explanation of the ways in which brain dysfunctions produce their experiences.” (my emphasis)

I agree with the overall point here, but Kendler appears to be holding on to the assumption that there are indeed “brain dysfunctions” that produce the experiences of mental illness. If this is the case, it means he is basically saying that we should hold off on talking about these brain dysfunctions until we have something empirically and scientifically meaningful to say, but rest assured, one day we will have something substantive to say about these brain dysfunctions. But until we have something scientifically meaningful to say, why should we even hold on to the vague and empty assumption that there are “brain dysfunctions”?

And if by “brain dysfunction,” Kendler simply means “whatever the brain mechanisms of mental health problems will turn out to be,” that’s technically fine, but also explanatorily empty and potentially misleading, and contradicts the spirit of Kendler’s own conclusion.

The elusiveness and immaturity of brain metaphors of psychopathology

Kendler writes:

“We have a very imperfect sense of the brain-based disturbances that predispose our disorders. We should not be ashamed of this. We have been working hard for a very long time on a set of problems of extraordinary complexity. Talking about our profession and our disorders to ourselves, our colleagues and patients using metaphorical brain talk is scientifically immature and ultimately disrespectful to our patients… We should tell them what we know, with all the uncertainty. We should take pride in being the only specialists in medicine that have chosen to treat the disorders of the mind, conditions that account for a large proportion of aggregate human suffering. We need not try to hide the large amount we still do not know about the causes of mental illness behind metaphorical brain talk.”

Amen! However…

Because of how Kendler defines metaphorical brain talk, and considering the examples Kendler presents in the article, it is difficult to pin down what genuinely constitutes metaphorical brain talk and what makes it problematic.

Furthermore, because Kendler remains committed to the “rigorous scientific reductive agenda in modern psychiatric research that seeks to understand the etiology of psychiatric illness” and the continued talk of “brain dysfunction,” it remains unclear what exactly it means to give up metaphorical brain talk, at least in the scientific context.

I’ll add a further complication to the mix. Our everyday as well as scientific thought remains steeped in metaphors. We are working with layers and layers of metaphors that only become obvious once one starts paying attention to them. Consider concepts like psychological trauma (uses physiological trauma as analogy), psychodynamics (uses thermodynamics as analogy), psychological impulses, mental conflicts, neuroplasticity, brain networks, cognitive distortions, brain computations, and feedback loops, which are all metaphors but also have their specific abstract definitions, which obscure their nature as metaphors. Physics is full of metaphors that have been made precise and scientifically useful (forces acting at a distance, space-time curvature, quantum waves, etc.).

The history of neuroscience can be written as a series of metaphors for the brain.

The ubiquity of metaphors in science

Metaphors are unavoidable in scientific thought. That’s just the way it is.

I’m going to quote liberally from a 2022 article on metaphors in neuroscience by Alex Gomez-Marin:

“Four decades ago, linguists and philosophers George Lakoff and Mark Johnson published an influential book on the nature of metaphors. In Metaphors We Live By they argued that abstract thought is mostly metaphorical (having a literal core extended by mutually inconsistent metaphors and therefore incomplete without them), that metaphors are fundamentally conceptual (while metaphorical language is secondary), and that metaphorical thought is ubiquitous, unavoidable, largely unconscious, and grounded in everyday life.” (Gomez-Marin)

Gomez-Marin explains how over the centuries, our metaphors for the brain have shifted almost as frequently as our technologies. In Descartes’ time, it was imagined as a hydraulic system, pumping “animal spirits” through the nerves like fluid through pipes. Later, with the rise of mechanical engineering, thinkers like Nicolas Steno cast it as a machine, and clocks became the new analogy, with gears turning and springs winding. Leibniz, ever skeptical, remarked that if you wandered inside a brain like you would a mill, you’d see mechanisms, but nothing resembling thought or sensation.

Electricity sparked the next shift. Galvani and Volta’s experiments reframed nerves as wires and the brain as a telegraph office, signaling across distances. But this metaphor, too, frayed under the weight of neural plasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt and reshape. Santiago Ramón y Cajal responded by reaching for organic metaphors instead: branches, forests, growth. Darwin, meanwhile, simply called thought a “secretion” of the brain, as if consciousness were akin to sweat or saliva.

The metaphors kept multiplying. We envisioned “conscious machines,” but then the machines began to look more like animals—dogs powered by circuits, beetles with gears, moths on wheels. As cybernetics took hold and feedback loops became scientifically respectable, the boundary between technology and biology grew hazy. Neural networks, pioneered by Pitts and McCulloch, blurred the line further. Suddenly, brains were like computers, and soon, computers were like brains. We updated our metaphors (networks, the internet, the cloud), but the fundamental question remains: how close are we to understanding the thing itself?

“Like fish in the sea, we often fail to notice the entrenched metaphors we swim in. Brains are not really any of those, and yet treating brains as such can provide valuable insights unless one does not erect one's favorite image into an idol. As Lewontin's quote of Wiener and Rosenblueth puts it, “the price of metaphor is eternal vigilance.” A metaphorical monoculture is a burden rather than a blessing. Glossing George Box's aphorism, all metaphors are wrong (when literally taken), but all are useful (when kept in their local domain of application). Screwdrivers are handy, but not to eat soup. Entertaining other ways to conceive what brains are, and what they do, is not only valuable but necessary.” (Gomez-Marin)

It is also telling that the very opening sentence of Kendler’s article contains a metaphor: “Psychiatry emerged as a medical specialty between 1780 and 1830 committed both to the care of the mentally ill and to the brain as the seat of these disturbances.” (my emphasis)

A metaphorical monoculture is a burden

Gomez makes an important point that a metaphorical monoculture is a burden rather than a blessing. Not only do we need a variety of metaphors for the brain in neuroscience and metaphors for the mind in psychology, we also need a variety of metaphors for psychopathology. The monoculture of brain dysfunction metaphors is a burden, not a blessing, and it needs to be challenged.

So what is the deal with metaphorical brain talk in psychiatry?

To summarize and bring the arguments together:

Metaphors are unavoidable in science, including the science of psychopathology. Metaphors, however, need not be empty or devoid of explanatory content. They can be scientifically precise, epistemically virtuous, and empirically supported.

Brain metaphors and other brain explanations in psychiatry can be problematic for a variety of reasons:

they unnecessarily rephrase or redescribe mental processes in neurological terms

they are vague to the point of being empty or they are too flexible and unfalsifiable

they reflect an uncritical reductionistic bias (what Jaspers called the “somatic prejudice”)

they are scientifically naive (grand monocausal explanations like the monoamine hypothesis of depression)

they are conceptually confused (e.g., they conflate a metaphysical physicalist position with the view that mental disorders are discrete, disease entities in the brain)

When using brain metaphors in psychopathology, we have to be mindful of the different philosophical ways in which the relationship between the categories of “mental disorder” and “brain disorder” can be understood.

Scientific progress depends on metaphorical creativity, on scientists wondering, “What if X is like Y?” and then offering precise, formal characterizations of X in terms of features of Y, teasing out the predictions this entails, and then subjecting those predictions to empirical testing.

Progress in the science of psychopathology will also require new metaphors. We should not shy away from them. However, in communications with patients and the public, we indeed have to tell it as it is. We have to acknowledge the uncertainty, and we have to abstain from metaphors that are scientifically immature and ultimately, as Kendler puts it, disrespectful to our patients.

See also:

Provided we contextualize these associations within a scientifically robust theoretical understanding of the relationship between brain and behavior, that psychiatric categories involve many areas of the brain, there is no one-to-one mapping, and emotions emerge from a process that involves complex dynamic interactions in a highly context-dependent manner

From the perspective of a patient who has wrestled with difficult psychological symptoms since the age of 7 (my initial breakdown) I knew early on that no scientist understands the brain, the most complex organ in the body, except on a most rudimentary level.

As a coping technique, I have learned to distinguish delicately between the aspects of my psyche that I can reliably influence and symptoms that ambush me and may take weeks of engagement to subside. Thus, for me the concept of a broken brain has freed me from unrealistic responsibility for the things that have proved quite resistance to my personal intervention.

Consequently, I can be happy about the things between my ears that work well and cope peacefully with those that don't. To sum up, the broken brain metaphor has been invaluable to me.

Enjoyed this, particularly learning that Kraepelin was a critic of biological overreach - I sometimes imagine him as the personification of biological psychiatry!