Personality Disorders as Relational Disorders

Insights from a computational perspective on personality pathology

Orestis Zavlis is a PhD student at the Psychoanalysis Unit in University College London. His work focuses on how to integrate psychoanalysis with computational science, as well as how to better define personality disorders. His recently launched Substack, “Personality Disordered,” aims to address the latter by critically examining assumptions surrounding the concept of personality disorder.

‘‘The self comes from the other,’’ proclaimed Hegel—highlighting that even our most personal quality, our very own sense of selfhood and identity, does not emerge ‘from within,’ but rather from our dialectic engagement with a social landscape. Almost a century later, Freud (along with other psychoanalysts) deepened this insight by suggesting that our minds are not self-determined entities; rather, they are shaped by early caregiving relationships: When those relationships are stable, humane, and ‘good enough,’ they lay the foundations for personal worthiness, agency, and emotional stability. When those relationships, however, are unstable, inhumane, or even altogether absent, they lead to various psychological problems, which are unfortunately now known as ‘personality’ problems.

In a recent paper, my team and I leveraged this relational way of thinking to construct an explanatory model that conceptualizes ‘personality disorder’ as a ‘relational disorder.’ Our model was published in a special issue that focused on ‘Revitalizing the future of personality disorder science and practice’. This special issue reflects what many personality researchers now acknowledge: namely, that the field of ‘personality pathology’ is currently stagnating.

Our view is that the field is stagnating because it relies exclusively on descriptive models that can only describe what personality pathology ‘is’ without explaining how it ‘operates.’ To briefly elaborate, descriptive models (like factor models) can only be used to identify the most central difficulties of ‘personality’—showing, for example, that difficulties with establishing an identity, social relationships, and direction in life lie at the heart of what we call ‘personality pathology.’ However, although useful in describing these ‘personality’ difficulties, descriptive models fall short in terms of explaining how these difficulties ‘operate’—for instance, such models rely on abstract and simplistic entities (such as the ‘general factor of personality’) to explain how these difficulties emerge, persist, and ameliorate.

Generative models can address these explanatory shortcomings. These models move beyond description and into explanation by outlining precisely how psychological phenotypes operate—in this case, by outlining precisely how ‘personality’ and its putative ‘pathology’ operate. This approach is based on computational psychiatry, a relatively nascent field that views mental disorders as computational disorders: that is, disorders of miscomputations (for example, anxiety as a misestimation of threat and psychosis as a misattribution of salience). In our paper, we adopted this approach to construct a generative framework that explains precisely how ‘personality disorder’ emerges, persists, and ultimately ameliorates.

In constructing this formal framework, we began by making explicit a few key assumptions. The first and most central assumption is that the fundamental function of personality is twofold: to (1) adaptively experience oneself and others in order to (2) adaptively relate to oneself and others (that is, to minimize self-other suffering and maximize self-other flourishing). This assumption follows from a wealth of evidence suggesting that ‘personality disorders’ are typified by difficulties in ‘mentalizing’: that is, difficulties in understanding oneself and others in intentional terms (i.e., in terms of thoughts, feelings, and wishes; see work by Peter Fonagy and colleagues at UCL). Our model follows this line of inquiry and suggests that these ‘mentalizing’ difficulties lie at the heart of most clinical problems in people with ‘personality disorder’ (e.g., problems with establishing a coherent identity and long-lasting relationships).

A second assumption is that this perception of ourselves and others is not passive (that is, you passively perceiving that your partner is not responding to your texts) but rather active (that is, you actively fantasizing that your partner is not responding to your texts because they are busy talking to others). This assumption follows directly from enactive approaches to psychiatry that place fantasy and meaning-making at the heart of human flourishing and suffering (see Friston’s active inference and de Haan’s enactive psychiatry).

A third assumption builds further on this meaning-making process to suggest that the ways we fantasize about ourselves and others are predicated on deeply held beliefs about ourselves and others—beliefs that are sometimes inaccessible to consciousness. This idea—that fantasy is based on unconscious beliefs—is predicated on a wealth of developmental, neuroscientific, and computational evidence suggesting that our metacognitive capacity to fantasize about disparate mental states is rooted in representational concepts (i.e., archetypes of what it means to be ‘good’ or ‘bad’) that were acquired during early development (see research by Jean Knox, Lisa Feldman Barrett, and Katerina Fotopoulou).

Finally, a fourth assumption is that these personality processes are dynamic: that is, they shift across time and space. This assumption is based on longitudinal evidence showing that various functions of personality (like ways of thinking, feeling, and relating) manifest in a context-driven manner—such that even someone who is extremely ‘stable’ in most life contexts could still become extremely ‘unstable’ in various other contexts (see research by Aidan Wright, Chris Fraley, Chris Hopwood, and colleagues).

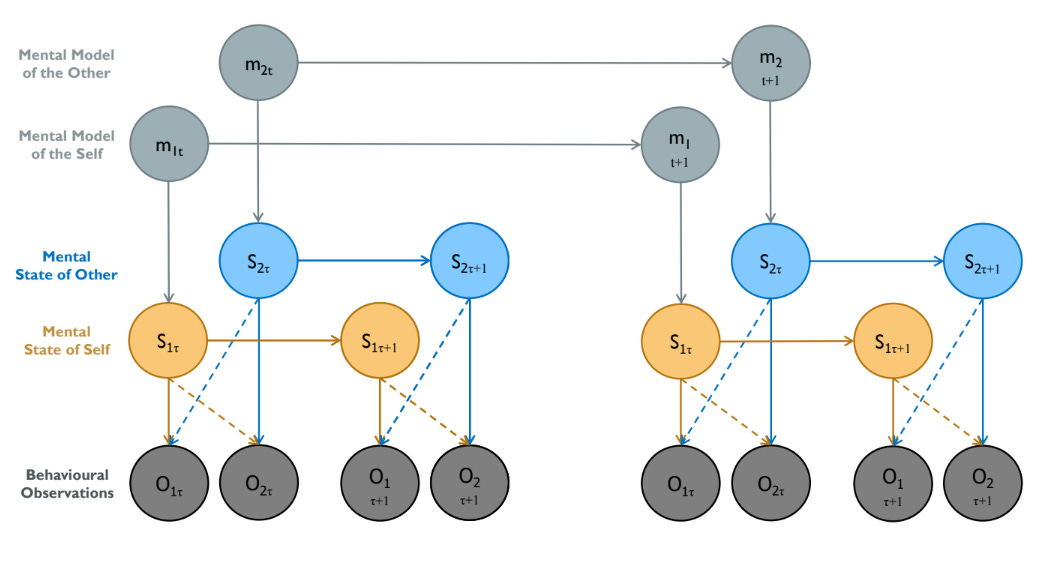

Using these axioms, we created a probabilistic framework that outlines precisely how personality pathology operates. This framework is visualized in the graphical model below (Figure 1). In this graphical model, circles denote variables and directed arrows denote causal associations among those variables. Here, we set up the causal architecture of our variables so that it tells the following story: namely, that deep and unconscious beliefs about ourselves and others combine with observed behaviors from ourselves and others to determine how we experience ourselves and others in this moment and in the long term.

This process is known under various terms (such as ‘social inference’ and ‘mental inference’) and has been the topic of extensive research (see, e.g., research by Michael Moutoussis, Giles Story, and Joseph Barnby). In our paper, we built upon this research to test whether personality disorders could be more accurately understood as relational disorders: that is, disorders in the ways patients ‘mentalize’ and ‘relate’ to themselves as well as others. To do so, we performed three simulations that show exactly how problems of ‘personality’ could be more accurately understood as problems in this process of ‘mental’ or ‘relational’ inference.

Results of 3 Simulations

1) "Personality" problems can be formalized in terms of too much internal or too much external mentalization

2) Maladaptive ways of experiencing and relating to the self and others develop from the ways we internalize early caregiving relationships

3) Personality problems can be ameliorated by clinicians relating to patients in an ‘authentic,’ ‘compassionate,’ and ‘non-judgmental’ mannerOur first simulation showed that prototypical problems of ‘personality’ can be generated by either too much internal mentalizing or too much external mentalizing. Internal mentalizing places more emphasis on mental representations of past relations and is thus more ‘internal’ and ‘transferential’: the self and other are viewed in more rigid ways (i.e., idealized or devalued) as their behavior is explained primarily in terms of one’s previous (maladaptive) relationships. External mentalizing, on the other hand, places more emphasis on social observations and is thus more ‘external’ and ‘ephemeral’: the self and the other are viewed as empty vessels, ready to take any form (the lover, the villain, etc.) based on their most recently emitted behavior. Our first simulation leveraged this formal way of understanding mentalizing and illustrated that rigid problems of ‘personality’ (like split ways of viewing others) and plastic problems of ‘personality’ (like unstable ways of viewing the self) can be formalized in terms of too much internal vs. too much external mentalizing, respectively.

Our second simulation extended these patterns by showing how they develop and persist over time and space. Specifically, this simulation showed that maladaptive ways of experiencing and relating to the self and others develop from the ways we internalize (or ‘probabilistically learn’) early caregiving relationships: When these relationships are ‘polarized,’ they promote overly positive (narcissistic), or overly negative (depressive), or overly split (i.e., both narcissistic and depressive) ways of viewing the self and/or others. When those relationships, however, are ‘disorganized’ (that is, sometimes positive, sometimes negative in a highly random way), they promote an ‘empty’ (or uncertain) way of viewing the self and/or others. Importantly, once these problems are established, they tend to get perpetuated socially: for instance, if a person tends to relate to others in a ‘negative’ manner, others will tend to relate ‘negatively’ back to them—ending up reinforcing that person’s already skewed mental model. In that sense, ‘personality problems’ are rarely ‘personal’; instead, they are ‘interpersonal’: they arise from our dialectic engagement with others—and, specifically, whether those others (caregivers, friends, or the entire social order) tend to ‘contain’ them (and, in the long run, dismantle them) or tend to ‘react’ to them (and thereby reinforce them).

Finally, based on these patterns, our final simulation illustrated that one of the most important ways of ameliorating ‘personality problems’ is by better relating to our patients. Specifically, instead of relating to our patients in a ‘reactive’ manner (by taking their ways of relating to us personally), we should be relating to them in an ‘authentic,’ ‘compassionate,’ and ‘non-judgmental’ manner (by appreciating that most of the time they relate to us, they are not in fact relating to us but rather are relating to ‘ghosts’ from their past). By recognizing that our patients’ ways of relating are not intentional but rather implicit, habitual, and quite automatic, we can stop relating to the ‘traumatized’ parts of their personality (e.g., by assuming that they suffer from disorders of ‘all personality’) and start, instead, relating to the ‘authentic’ parts of their personality (e.g., by coming to appreciate that they suffer from developmental failings which could be revitalized in the context of a new relationship).

To briefly summarize, our simulations illustrated that when personality is cast in more enactive terms, it is best understood as a dynamic system that propels patients to relate to themselves and to others in particular manners. In that sense, personality disorders can be functionally understood as relational disorders: disorders of self-relatedness and other-relatedness.

I deeply believe that there are many important implications with this framing of ‘personality pathology’—not least the more precise labelling of disorders of ‘personality’ as disorders of ‘relating.’ Although most of these implications have been explored in our paper, I would like to briefly conclude with what I believe to be the most important one of them: specifically, the idea that ‘personality pathology’ is best conceived not as a deficit in ‘personality functioning’ but rather as an imbalance in the dialectic motives of self-functioning and social-functioning.

We are made by relationships. Most meaning, as well as suffering, is found in relationships. Our entire sense of self only makes sense within the context of relationships.

Historically, this was uncontroversial and intuitive: Personality, to use Sydney Blatt’s terms, comprised two clearly defined, higher-order domains: autonomy (i.e., the desire to be alone and ‘get ahead’) and relatedness (i.e., the desire to be with others and ‘get along’ with them). In recent times, however, these domains have been unfortunately conglomerated into the elusive concept of ‘personality functioning’—reifying the idea that there is a general latent entity, ‘personality,’ that causes difficulties in self-relating and other-relating. In my eyes, this idea is both empirically and conceptually untenable because it simplistically assumes that problems in relating to the self and to others can be explained away by a single latent variable denoting one’s entire ‘personality.’ As our model, however, illustrates, self-relating and other-relating difficulties need not be explained away by reified entities; instead, they can be simply appreciated as separate yet interdependent properties that co-evolve over time.

To briefly illustrate, consider two patients who present with similar levels of distress and who both feel like they have failed in life. One, however, feels that they have failed themselves, while the other feels that they have failed others. The first person is aloof, hard-working, and only cares about succeeding professionally; the second person is less orderly, more socially sensitive, and struggles to feel whole without an ‘other’ by their side. A rudimentary diagnosis may be ‘narcissistic personality’ (that propels the first person to mainly relate to themselves and neglect their relationships with others) and a ‘dependent personality’ (that propels the second person to mainly relate to others and neglect their relationship with themselves).

In this context, the treatment of these patients would vastly differ, as every clinician would appreciate that the former patient needs to ‘get outside their head’ and relate more to others, while the latter patient needs to ‘get outside the social order’ and relate more to themselves. In Freud’s terms: the first person needs to love more while the second person needs to work more. Conglomerating love and work into a single dimension is one of the most unfortunate things that has happened in contemporary models of personality and will only continue to obscure rather than elucidate by appealing to abstract latent entities in an attempt to explain what every human being intuitively perceives: namely, that we are made by relationships; that most meaning, as well as suffering, is found in relationships; that our entire sense of self (and ‘personality’) only makes sense within the context of relationships.

So long as the field of personality continues to ignore these fundamental insights on human life, it will persist in reifying solipsistic entities that make no sense empirically, theoretically, or even ethically (as most patients with lived experiences would agree that their personalities are not in fact ‘disordered,’ but only their self-experience and social-experience are ‘disordered’). The only way ahead is to move away from abstract concepts like ‘personality functioning’ or ‘personality pathology’ and toward specific concepts like ‘self-relating’ and ‘other-relating.’ The only way ahead then is to reconceptualize disorders of ‘personality’ as disorders of ‘relating.’

See also:

I just wanted to post this comment to thank everyone for the thoughtful engagement with this post! I also wanted to clarify one more thing, if I may: Beyond the specifics of the model, there is an overachieving theory that deserves equal if not more mentioning.

This theory moves away from traditional assumptions that view disorders of personality as disorders in all personality domains (e.g., thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating) and toward the idea that such disorders might be disorders in primarily one such domain (i.e., the domain of relating).

I wanted to draw this dichotomy (between theory and modeling) because this theory could be tested in many different ways (that exclude the specifics of this model).

Best Wishes,

Orestis Zavlis.

Fascinating piece! I just have a clarificatory question:

You say that in your paper you used a generative model to “test whether personality disorders could be more accurately understood as relational disorders.” But what actually constitutes this “test”? Did you, for example, check if your model outcomes fit better with existing data than those of competing models of personality disorders? In this post, you only mention running simulations but those alone cannot have been the test because their first basic assumption is that personality disorders are relational disorders*, and so they would have left that claim untested. However, if this is what you did then I think that it is more accurate to say that you simulated possible explanations of how a personality disorder works on the assumption that it is relational, rather than actually test that claim.

Very happy to be corrected, of course 👍

(*I’m a complete subject neophyte but this surely follows from the claim that part of personality’s fundamental function is relational?)