Reflections on “Psychiatry at the Margins”

"Being a competent public intellectual is a labor-intensive endeavor."

Psychiatry at the Margins is a one-person-plus-friends operation. It is a labor of love, something I am juggling in addition to a full-time clinical job, academic obligations, and family responsibilities. It is also a text-based publication, and although I appear on podcasts at times, I remain wary of producing audiovisual content myself. In a world where attention is scarce, online engagement is driven by video platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok, podcasts are preferred sources of information for large numbers, and social media algorithms dictate what you come across, I try to be realistic about what I can achieve with my methods. For a newsletter about psychiatry and psy-disciplines that often goes into fairly technical issues, doesn’t spoon-feed readers, and is interested in examining critical issues in psychiatry without resorting to the sort of polarizing rhetoric that sells well, it is nonetheless reassuring to see so many of you interested in what Psychiatry at the Margins has to offer.

My goal has been to use this newsletter as a venue to think through complicated issues relevant to psychopathology and psychiatric practice and to highlight good work that is being done. I don’t have all the answers; no one does. I’m not infallible; I have my own biases. The goal is neither to promote nor bash the psychiatric profession.1 The goal is to engage in a process of critique and reflection and to improve our collective understanding of psychiatric phenomena.

This publication is unlikely to go viral, become the go-to source for latest developments in the field, or wield the sort of influence that popular platforms hostile to psychiatry wield. However, I believe this publication nonetheless has an important role to play by making the conceptual and scientific nuances around mental illness and psychopathology accessible to a wider audience that includes trainees, clinicians, researchers, policymakers, editors, journalists, activists, patients/service users, and the general public. I am proud that Psychiatry at the Margins has become a space where a psychiatric survivor talks about how she found her way out of anti-psychiatry, a psychiatric consultant discusses how her own lived experience and her encounters with critical perspectives have changed her practice, a psychoanalytic psychologist writes a 3-part series on Thomas Ogden, and a former NIMH director comments on the genetic complexity of mental disorders.

In order to celebrate the milestone of 10K subscribers, I reached out to a few select friends with the invitation to reflect on the role I, and future guest contributors, can play via this newsletter in the contemporary online landscape of information and opinion. I am honored to share their responses.

Peter Zachar

Peter Zachar, PhD, is Professor in the Department of Psychology at Auburn University Montgomery and a Fellow in the Association for Psychological Science. His primary area of scholarship is philosophical issues in psychiatric classification and the history of classification in psychiatry and psychopathology.

In Psychiatry at the Margins, Dr. Awais Aftab offers a masterclass in executing the core missions of a public intellectual. Public intellectuals are teachers who educate their audience about both established and emerging ideas, but their mission is also to elevate the quality of debate, discourse, and conversation.

More involved than expressing one’s opinions, being a competent public intellectual is a labor-intensive endeavor. For example, consider how extensive the intellectual landscapes for psychiatry and related disciplines are. To map them out is a challenge—to keep updating the maps even more so. Awais excels at such intellectual map-making—and takes it further by interpreting the maps. As a result, Psychiatry at the Margins functions as a curated guidebook spanning clinical psychiatry, academic philosophy, and the various mental health sciences—supplemented with regular appearances by local experts.

Reading guidebooks and watching travel shows about places you hope to visit is enjoyable, but they are even more engaging when they are about places you have visited because you get more out of them. The same is true for Psychiatry at the Margins. It is an enjoyable way to learn about innovative ideas and movements but is even more engaging when it explores topics you are invested in or have worked on yourself.

Years ago, some universities offered the option of doing a PhD in general psychology. This was a push back against the trend toward narrow specialization, but in addition to generalizing knowledge across multiple and different areas of psychology, my understanding is that the general psychology track was both a ‘forest and trees’ degree where one was expected to also acquire specialized knowledge in multiple areas. It was best suited for extraordinarily bright and exceedingly motivated people. That is the template that Psychiatry at the Margins has been patterned on, and thus it helps elevate the thinking of its whole audience, including the general population, service users, and various specialists.

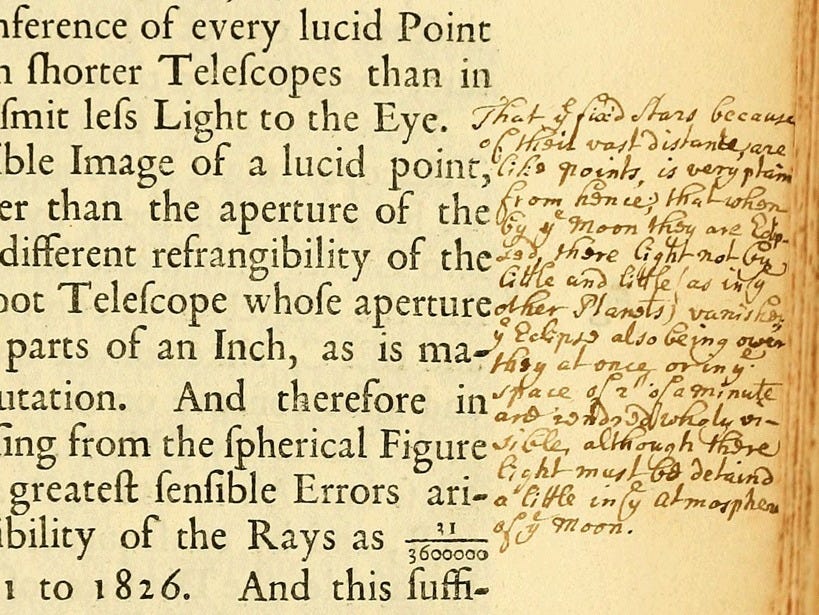

In Psychiatry at the Margins, the “margins” may refer to the overlapping boundaries between psychiatry and related disciplines, but margins are also where we can make notes and scribble out insights to augment and amplify what is already on the page. Likewise, Psychiatry at the Margins is an invitation to ponder what is already on the page and hopefully join in and augment the discourse, debate, and conversation.

Nicole C. Rust

Nicole C. Rust, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of the forthcoming book “Elusive Cures: Why Neuroscience Hasn’t Solved Brain Disorders—and How We Can Change That.”

The mental health field is transforming at all levels, from basic research to clinical practice, following new developments in artificial intelligence and biotechnology. As these transformations happen, we researchers and clinicians need to do more than just keep up; we need to synthesize what’s happening to decide how to best use the new opportunities presented to us. Moreover, we need clearheaded ideas about how we will arrive at new treatments that will better help individuals with psychiatric conditions. In its two years, Psychiatry at the Margins has helped advance the much-needed discourse in this space.

The human brain and mind are often held up as the most complex things in the known universe. By extension, the psychiatric conditions are among the most mystifying of all natural phenomena. The challenges we face in the mental health space are formidable, and there’s a tremendous amount of sense-making to be done. Psychiatry at the Margins has already made valuable contributions in that realm. As the newsletter moves forward, I hope Dr. Aftab and other writers will contribute in three complementary ways.

The first is by identifying holes in our existing knowledge. What exactly should we prioritize knowing about the brain and mind to arrive at the type of meaningful understanding that can lead us to the end goal of new and more effective treatments for psychiatric conditions? The conversations required lie at the nexus of psychiatry, psychology, neuroscience, and philosophy, and they require bridging conventional silos.

The second is through the synthesis of what’s happening in ever-evolving clinical psychiatric practice. As new therapies are introduced (such as the new class of antipsychotics and the undoubtedly forthcoming psychedelics), to what degree are they filling the unmet need not just in principle but in practice?

The final contribution I look forward to is the continued questioning and challenging of the status quo. For instance, many studies demonstrate that cognitive behavioral therapy (and other behavioral therapies) are as effective or more effective than medications. Yet, these behavioral therapies are underutilized as first-line treatments. Why?

Congratulations to Dr. Aftab and Psychiatry at the Margins for reaching the milestone of two years and 10,000 followers! I’ve learned a lot from you, and I look forward to your next steps.

Jim Phelps

Jim Phelps, MD, is a psychiatrist who retired from patient care after 30 years treating complex mood disorders. He is the author of several books on a spectrum approach to mood disorders. He continues to offer bipolar psychoeducation via DepressionEducation.org; and BrainstormTheFilm, a documentary about the bipolar spectrum, including a weekly podcast with the film’s interviewees.

What role can Psychiatry at the Margins (PATM) play, looking ahead? So far I’ve found the essays fascinating much of the time; but sometimes over my head, steeped in philosophical jargon and ethereal concepts. Sometimes the back-and-forth sounds to me like dissecting minutiae (angels on pinheads, etc).

I recognize that this is my problem: I don’t understand the exchange well enough to appreciate the important distinctions being made. They look subtle or abstruse. Yet I trust Dr. Aftab’s experience and intelligence enough to know that the discussion must be worthy of attention.

By comparison, my more earth-bound mind wants to focus on problems that seem simple by comparison: (1) the fact that the majority of mental health care is delivered in primary care by well-meaning practitioners who do not have the knowledge and time to do that job well; and (2) the societal misunderstanding of mental illness as shaped by decades of DSM categorical labeling.

My preference for PATM , for what it’s worth, would be to move away from deep philosophical inquiry (sorry, Awais) and toward the societal and philosophical implications of new research findings. For example: if we have a “blood test for bipolar” as per Salvetat et al 2022, will people forget that such tests don’t make diagnoses, they change a prior probability to a posterior probability? How can we frame this concept for the general public? How can we talk about these tests in a way that does not further reify DSM categorical diagnoses?

Another example: a former primary care doc’ turned psychiatrist, Cynthia Calkins, led a study of patients with treatment-resistant bipolar depression and insulin resistance. Her group found a dramatic reduction in MADRS scores with metformin (15 points, about same as in quetiaine’s RCTs), among the patients whose insulin resistance reversed. This result clearly implies that by using antipsychotics that cause metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar depression, we are causing, in a subset, the very thing we are trying to treat.

(Note that in Salvetat et al, 64% of the patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder were taking an antipsychotic—perhaps necessitated by an antidepressant, which 50% of the sample were also taking.)

This is outrageous. Where is the hue and cry? Waiting for a replication, perhaps; that would be a positive assumption. More to the point for PATM: can we stand by and watch our colleagues induce treatment resistance? What are our responsibilities toward them? On the other hand, given that injustices abound across the globe, perhaps this one does not warrant crossing professional boundaries and disturbing tenuous relationships. Perhaps we should wait for a replication after all.

Suffice to say that my wish for PATM is that it continue to provide psychiatry with high-level intellectual inquiry, as it has done ably to date; and that perhaps the focus might shift, at least slightly, in the direction of practical implications and applications.

Sofia Jeppsson

Sofia Jeppsson is an openly Mad philosophy professor at Umeå University in northern Sweden.

I always recommend this blog to people who want to keep up with psychiatry. I recommend it to psychiatrists and other clinicians, philosophers of psychiatry, neurodivergent and madpeople interested in research pertaining to their own diagnoses, and just about everyone who might be interested. Perhaps I should also start recommending it to philosophers of time, because it does seem like Awais Aftab has found a way to squeeze out more than 24 hours of each day—this substack seems like a full-time job in itself!

It’s not just that Psychiatry at the Margins is so comprehensive and covers so much—it’s also critical, in the best sense of the word. This is rare in today’s polarized media landscape. Zooming in on psychiatry, so many popular pieces present a ridiculously simplified and biologically focused view on psychiatric conditions: it’s because of genes and neurology, hypo- or hyperactivity in different parts of the brain, imbalanced neurotransmitters in what’s basically a re-emergence of the medieval humour theory—only with dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, and adrenaline instead of the blood, phlegm, and black and yellow bile of old. We haven’t managed to fix people yet, but we will, soon—the big biological breakthrough is forever just around the corner. And then, on the other hand, we have the counter picture, where psychiatry is a terrible, pseudoscientific, oppressive hocus-pocus. People on the counter side of things are sometimes prepared to mix and match reductive biological explanations (must be inflammation of the brain, the solution is strict keto diets for all!) with psychoanalysis and everything in between, as long as it’s not modern mainstream psychiatry with its pills.

In my job, I frequently come into contact with both sides. But most people who think they know a thing or two about psychiatry are likely stuck in one or the other media bubble.

Psychiatry at the Margins is a wonderful antidote to all this polarization. It provides all the complications, uncertainties, and nuances normally lacking from reports on psychiatric research, with a keen sensitivity to how much psychiatry intersects with philosophy and other fields.

So where would I like to see Psychiatry at the Margins go in the future? Beyond continuing, of course, to provide that antidote? Two thoughts:

First, I’d like to read more about “experts by experience”, or whatever you want to call this group. There is some ongoing debates and research on what this even means; what kind of expertise is expertise by experience? Having had, e.g., psychotic experiences, doesn’t mean that you now know what it is like to be psychotic, because one person’s psychosis isn’t like the others. Still, you know something that your doctor likely doesn’t know, regardless of how well-educated they are in clinical matters. There’s a tension between the dangers of elite capture—having a small group of unusually successful and privileged madpeople speak for all—but also, in my experience, a danger of dismissing everyone who seems successful or happy as “not representative.” People who get invited to medical events to share their “lived experience” further report feeling like they have to walk a tightrope between repressing all their criticism of psychiatry—thus rendering their presence pointless—and being too critical and therefore end up dismissed. Overall, there’s so much to discuss here.

Moreover, I enjoyed Susan Mahler’s guest post about fictional accounts of shame, and the poetry post. Perhaps we should have more art and art discussions in the future?

Jesus Ramirez-Bermudez

Jesus Ramirez-Bermudez, MD, PhD, is a psychiatrist who works at the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery of Mexico, where he is engaged in clinical practice, teaching, and research in the field of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences.

Since its first post, I have been a dedicated reader of Psychiatry at the Margins by Awais Aftab. I was already familiar with Aftab’s philosophical essays and the stimulating discussions he published in the Conversations in Critical Psychiatry series in Psychiatric Times. Through Aftab’s arguments, it became clear to me that psychiatry needs to actively engage in a pluralistic discussion on mental health, psychological well-being, and its relationship to medicine and social contexts. As a clinician and researcher, I recognize the daily challenges we face in psychiatry, mental health, and clinical neuroscience. There are many success stories that provide reasonable hope, but also unexpected, unfortunate outcomes that compel us to examine these issues with the utmost care. The field presents fundamental questions and feelings of uncertainty not only to those who suffer but also to those who provide care. Researchers committed to an honest pursuit of knowledge are acutely aware of the uncertainty and the gap between clinical reality and our current understanding. Bridging this gap requires both scientific research and metatheoretical debate, given the diversity of thought and values in mental health.

Unfortunately, this necessary discussion is often polarized by academics who view the field in extremes—either wholly rejecting psychiatry or dismissing all criticisms of psychiatric practice. Psychiatry at the Margins makes an incisive and balanced contribution to the debate amidst this polarization. Aftab avoids the denialism common in some critiques of psychiatry, acknowledging the formidable and real problems currently framed as “mental disorders,” as well as the value of many interventions.

At the same time, he does not naively accept all psychopathological categories as reified by the DSM system and similar taxonomies. Through science-informed critical analysis, Aftab offers a nuanced view of the validity of these categories and the efficacy and safety of psychiatric interventions, considering the facts and the values under discussion. Aftab frequently includes insights from experts by experience, as well as practitioners across various mental health disciplines, including psychotherapists, philosophers, and academic critics of psychiatry.

Psychiatry at the Margins has been not only a reliable source of information on current scientific research but also a model of the pluralism needed to improve psychiatric interventions and the broader social debate on mental health.

See also:

Occasionally someone subscribes to the newsletter thinking that I share their hostility towards psychiatry. They are understandably disappointed after reading what I have to say, and then they’ll unsubscribe with a frustrated note along the lines of, “You just pretend to be critical!”

"For instance, many studies demonstrate that cognitive behavioral therapy (and other behavioral therapies) are as effective or more effective than medications. Yet, these behavioral therapies are underutilized as first-line treatments. Why?"

I think that the answer to this question is so obvious that I am deeply tempted to think that the question is rhetorical and Prof Rust is fully aware of the answer.

The answer is that dispensing a pill is the cheapest way to address virtually any medical issue—unless that pill is remarkably expensive.

Cognitive behavioral therapy involves at least some human intervention, which comes at a high hourly rate. Similarly, if sports coaching could be replaced by a pill that was half as effective, all sports coaching would quickly disappear except on the pro level (which of course includes Division I college sports).

Of course, it may soon be that an AI cognitive behavioral therapist will be as good as the median human cognitive behavioral therapist.

As it is, I received input for my own self-practice of cognitive behavioral therapy from reading two books on the subject several decades ago. This was a human intervention— but not one that every service user can take advantage of.

Incidentally, service user is marginally better than patient, but it is ghastly in its depersonalization and deemphasis on autonomy. Any use of the word service deemphasizes autonomy.)