The Conceptual Muddle of Addiction and Recovery: A Discussion with Carl Erik Fisher

Carl Erik Fisher, MD, is an addiction physician, bioethicist, writer, and person in recovery. He is an associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, a fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and the American Society of Addiction Medicine, and a member of the American Psychiatric Association’s Council on Psychiatry and Law. He is the author of the nonfiction book The Urge: Our History of Addiction, published by Penguin Press in January 2022 and named one of the best books of the year by both The New Yorker and The Boston Globe. He has published his academic work in JAMA, The American Journal of Bioethics, The Journal of Medical Ethics, and elsewhere, and his writing for the public has appeared in outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian, and Slate. Fisher also maintains a private psychiatry practice with a particular focus on psychotherapeutic approaches incorporating mindfulness and meditation. He is the host of the Flourishing After Addiction podcast, a deep-dive interview series exploring addiction and recovery, and he writes at the Substack newsletter Rat Park.

Awais Aftab, MD, is a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University. He is interested in conceptual and philosophical issues in psychiatry and is the author of Psychiatry at the Margins.

Aftab: I really enjoyed reading your 2022 book The Urge: Our History of Addiction when it came out, and I’ve enjoyed following your writings on your Substack newsletter Rat Park. Tell us about Rat Park and what you hope to do with the newsletter. How does Rat Park relate to the work you’ve done previously in The Urge?

Fisher: Thank you for these kind words, which mean a great deal to me, coming from someone I respect as a keen and thoughtful observer of psychiatry today.

The Urge focused largely on understanding addiction, but I felt like I was only able to scratch the surface of what’s commonly called recovery. The point of Rat Park is to focus a bit more on the positive side of addiction and recovery, while retaining a healthy respect for the complexities and nuances of these topics—and Substack seemed like a good place to do that.

The slightly longer origin story of Rat Park is that I had the idea for a series of writings about addiction recovery that were too casual and provisional for academic publication, too short and unformed for a book, but too long and otherwise just not right for magazine writing. In the meantime, I was inspired by all the great writing happening on Substack (including your own) that, for lack of a better term, could be called “academic-adjacent,” so I thought I would give the platform a try. I’ve really enjoyed playing with the form, and Rat Park is still evolving.

I just finished that initial set of writings: a 5-part series on frameworks for understanding this idea of recovery. To be frank, I think it was only partially successful. I wanted Rat Park to be an experiment in publishing more off-the-cuff work, but I found myself writing longer and slightly more serious posts than I had imagined. So going forward, I plan to write even more provisional, conversational, exploratory work.

For example, one post I really enjoyed writing was a behind-the-scenes conference report of the American Society of Addiction Medicine that became a comment on the false dichotomy between harm reduction and abstinence. I really enjoyed firing off that post, and people seemed to respond to it, but I also felt like I was cheating by writing it because it wasn’t in the “frameworks” series.

In the future, I plan for Rat Park to be a space for more of those spontaneous, informal discussions about recovery, thriving, flourishing, and addiction overall. I’ll continue exploring other themes I couldn’t fully address in The Urge, such as behavioral addictions and the idea that addiction is, in some respects, universal. I also intend to share practical resources and tools from my clinical work, which focuses on mindfulness-based, contemplative practices. As a way of fostering more real-time human connection, I’m also going to play around with live events, and I’ll be hosting a 90-minute interactive workshop in early September.

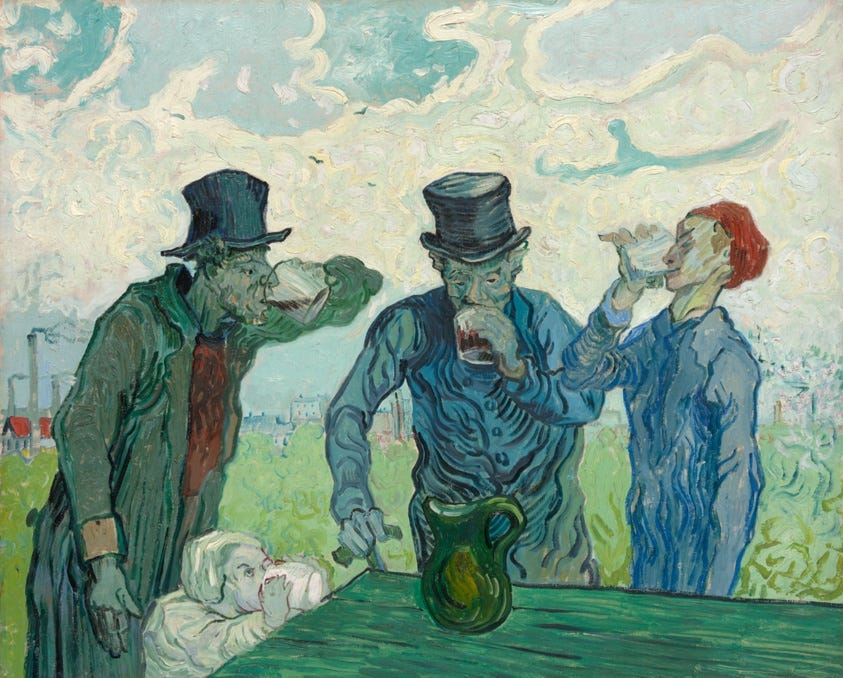

Aftab: I was glad to see that you advocated for a pluralistic conceptualization of addiction, which is the view I’ve ended up adopting with regards to psychopathology in general. You write beautifully, “Addiction is a brain disease, a spiritual malady, the romantic mark of artistic sensibility, a badge of revolution against a sick society, and all of these things at once.” In conversations with colleagues in addiction medicine/psychiatry and in conversations with patients, do you find this to be the default position? Or does one or another form of “monocausotaxophilia” remains dominant?

Fisher: Do most people have a sensible and thought-through position? Do clinicians or even researchers have a proper model for understanding addiction? My guess is no, at least in the majority of cases, and most people are running semi-consciously off a hodgepodge of different conceptual assumptions.

“What are the default beliefs about addiction held by providers and patients?” is also in some ways an empirical question, and there is some literature about “perceptions” and the like, which is very interesting and which I won’t try to review here. I also wouldn’t want to suggest that I know or have special insight into the default views held by most people. But anecdotally, especially since my book came out, I do have the benefit of working across a few different domains—clinical, psychiatric, bioethical, public-facing work, talks, and interactions with people across the whole spectrum of addiction care—so I will say a little about my casual experience.

Fisher: My sense is that humble and wise clinicians of all stripes naturally gravitate toward varieties of pluralism. Among the clinicians I look up to, whether they are psychoanalysts or behaviorists or psychopharmacologists or whatever, they seem to land on at least explanatory pluralism regarding the causes of addiction.

First off, my sense is that humble and wise clinicians of all stripes naturally gravitate toward varieties of pluralism. Among the clinicians I look up to, whether they are psychoanalysts or behaviorists or psychopharmacologists or whatever, they seem to land on at least explanatory pluralism regarding the causes of addiction. I have had this feeling since the early days of my training, before I could even articulate what “pluralism” meant.

In addiction medicine and addiction psychiatry, it seems most of the non-philosophically inclined clinicians and researchers do what people in general psychiatry do, which is to refer to the “biopsychosocial model.” I gather you share my view that “biopsychosocial” is often simply name-checked as a kind of flaccid, “anything goes” eclecticism. Then, in the communities more heavily influenced by the treatment-industrial complex (i.e., the stereotypical old-school rehab), the default view seems skew essentialist and reductionist, as well as coming with some degree of religious overtones depending on where you are in the country. Overall, I think many people who think and say they have a “model” don’t actually have a model but rather simply a rhetorical flourish, or at best a loose interpretation.

Relatedly, my experience is that even among people who reference biopsychosocial formulations, there is still a heavily essentialist and biologically reductionist view about addiction (i.e., framing the biological as the most important, “fundamental” level of explanation, and addiction as if it is clearly a separate, easily demarcated state of human existence). This is, of course, present everywhere, but I believe it is a bit stronger regarding addiction.

This is why I think your work on conceptual competence is useful, and something I’m interested in developing in the context of addiction care and policy.

As for patients, we should never underestimate the intelligence of our patients and the public, and their capacity to understand nuanced and sophisticated discussions of mental health and illness. The number of people who engage with your work on this Substack is a testament to that. At the same time, when people are scared, in pain, or otherwise struggling, they very easily revert to an explanation based on a single, simple cause. So, I’ve also often been surprised by how quickly very thoughtful people get sidetracked by monocausotaxophilia. That’s less about whatever model they might endorse and more about what happens in a crisis.

Aftab: A quote from The Urge:

“I knew I had a problem, and a big problem at that. But did I have addiction? Was it a thing—something I caught, or that took hold of me—or was it inseparable from who I was, lurking there in my personality or biology or karma for all time? Was it a separate entity that had attached itself to my healthier being, or was my self inclusive of the disorder? And would I have it for the rest of my life, even if I never drank or used again?” (pp. 268-269)

On recently re-reading parts of your book, I was reminded of my recent post on diagnosis and personal identity, “Psychopathology, Exhaustion, and Identity.” You’ve lived through exactly the sort of struggle that I was talking about… the sort that drives people to exhaustion. My impression is that those who carefully think through these issues and avoid the usual conceptual traps seem to converge on a dialectical tension between quantitative and qualitative change. Our existing concepts seem inadequate at capturing the simultaneous truths that characterize addictions and mental health problems. They are on a continuum with problems of living that are near-universal, and yet there are vital differences at the two ends of the spectrum that are important to recognize. You arrive at a similar conclusion in The Urge, where you understand addiction as one manifestation of the universal human experience of a loss of control and a loss of power, and yet you also recognize that addiction brings its own peculiar set of considerations with regards with diagnosis and treatment.

Aftab: Those who carefully think through these issues and avoid the usual conceptual traps seem to converge on a dialectical tension between quantitative and qualitative change.

Fisher: That’s an interesting connection. You’re right that exhaustion was an important feature of my experience. I love that quote from Jake Jackson about being “epistemically adrift:” “the sense that individuals face too many conflicting opinions and a constant debate of how to live […] that they are unable to process for themselves what their best options for living are.” At different points in my addiction and recovery, I’ve had different questions about how to live, i.e., I’ve been epistemically adrift and exhausted in different ways. That passage from my book was from my early recovery, when I was specifically wondering about the question: could I ever drink safely again?

By then, I had read in the professional literature that some of the usual folk psychological assumptions about addiction were questionable: substance use problems might not always be permanent, progressive, or irreversible. Even in severe cases, some people were able to return to moderate use. I was wondering, as many do, what to do with that knowledge, given that I had also accepted that I was far out enough on the spectrum to identify as a person with addiction?

Fisher: A major theme of the book is that dominant perspectives on addiction have overemphasized its supposedly separate, distinct, and abnormal status.

A major theme of the book is that dominant perspectives on addiction have overemphasized its supposedly separate, distinct, and abnormal status. Before I entered recovery, there seemed to be a stark division between normal and addicted, and I really wanted to be on the healthy side! In large part because of this attachment to my identity, I resisted identifying as a person with addiction for a long time. I clung to my self-image and perceived status as a normal, successful, worthy person, because to acknowledge addiction in myself felt like it would necessarily obviate those good qualities. Even in early recovery, a part of myself wondered, if I drank again, perhaps I could prove that I was “normal.”

The way I resolved that issue is described at length in the book, but the upshot is I had to get comfortable holding the seeming contradiction that, as you say, seemingly universal problems of living can exist on a continuous spectrum, yet there are meaningful enough differences at the ends of the spectrum to make it reasonable to identify as an alcoholic. I came to recognize that, if nothing else, my experience of addiction was phenotypic, in the sense that among all the people with addiction, whatever the underlying causes of our problems, we share a common experience of loss of control, as well as common-enough experiences of the interpersonal and social experience of addiction. I also had to see that being so tightly attached to a conception of myself as powerful, healthy, etc. was enough of a problem in and of itself. That made sense for me, as a relatively privileged person. It won’t make for everyone with addictive problems to identify as powerless.

Aftab: JD Haltigan and I recently had a discussion on a number of social issues interfacing with psychiatry, and one of them was “stigma” around addiction and how some folks argue in favor of retaining some form of stigma. I pushed back against that, but I did concede it makes sense to socially disapprove of certain addiction-related behaviors. I am wondering what you make of that exchange and how you would respond to the concerns raised around destigmatization.

Fisher: I’ve seen this line of argument a lot and my reaction is to fear that the word “stigma” has become so ideologically overloaded that it is approaching meaninglessness. Stigma is not a monolithic concept. There is a set of prejudicial and exaggerated views about addiction that we can call stigma: people with substance problems are necessarily dangerous to others, weak in character, at fault for self-inflicting their condition, and incapable of controlling themselves. These are dehumanizing ideas. But there is also the broader social disapproval of harmful behavior, which is something entirely different.

Similarly, at the intrapersonal level, there is a psychological literature on “self-stigma” (aka shame) in substance use disorders, and I interviewed one of the leading researchers on the topics, Jason Luoma, about how this is generally harmful. It is not “workable” in ACT terms; self-stigma doesn’t encourage but instead gets in the way of change. When people have a rigid concept of themselves as inadequate, damaged, and broken, they have trouble moving toward their own valued ends. But I also talked to the philosopher and person in recovery, Owen Flanagan, about possibly healthier varieties of shame. Owen has argued that shame has a crucial function in moral development, and that there are ways of working with healthy and mature forms of shame to promote positive values and flourishing.

I also see in Haltigan’s questions to you that he is lumping together “destigmatization” and “harm reduction,” which is a common rhetorical move but only adds to the muddle. I discuss the meaning of “harm reduction” at some length in The Urge, but the main point I want to emphasize here is that “harm reduction” can refer to both straightforward practices (e.g., syringe service programs) and to an overarching philosophy. And regarding an overarching philosophy, within harm reduction communities, there is extensive disagreement about what that philosophy entails! Is it just about advocating for drug user rights, or is it about wholesale transformation of the systems that create negative consequences for drug use?

Fisher: Let’s be clear about the concrete practices of harm reduction. There are certain evidence-based practices, including but not limited to peer education, naloxone (Narcan) distribution for overdose reversal, drug-checking services, and safe consumption facilities. Each of these practices has strong research support, showing that they reduce drug harms without increasing drug use or crime.

Let’s be clear about the concrete practices of harm reduction. There are certain evidence-based practices, including but not limited to peer education, naloxone (Narcan) distribution for overdose reversal, drug-checking services, and safe consumption facilities. Each of these practices has strong research support, showing that they reduce drug harms without increasing drug use or crime. These are straightforward matters regarding concrete measures of health in the context of a continued, historic overdose crisis. There is really no question about these interventions, although, as always, there are complications to their implementation. We shouldn’t let a broader debate about much thornier social issues contaminate the clear and necessary benefits of straightforward interventions like these. Yet these concrete practices are under attack across the country because of a sense that being “soft” on drug problems leads to permissive behaviors or “enables” drug use. This is a tragedy, and one born out of sloppy thinking.

You say, “it makes sense to socially disapprove of certain addiction-related behaviors.” Sure. Sometimes people with addiction do awful things. It would be ridiculous to deny that fact or to fail to disapprove of them. But I think we need to clarify what an “addiction related behavior” is. It’s important to be clear about problems of drug use versus problems of addiction. At least since the early 17th century, ideas about addiction have justified harsh prohibitionist policies that magnify the harms of drugs. But not all drug problems are problems of addiction, and vice versa.

I offer all those thoughts by way of conceptual clarification, which is of course the point of Psychiatry at the Margins.

All that said, I want to acknowledge that people are concerned about these topics because of real problems like drug use, crime, the housing crisis, and public disorder, and we are having trouble as a society finding a way out, especially in the US. I don’t want to dismiss those problems or say there are no issues with the way certain policies have been implemented. Clearly, certain policy initiatives presented under the banner of harm reduction (such as Oregon’s Measure 110, removing criminal penalties for drug possession within certain thresholds) have been botched, at the very least in the implementation, and probably in other ways too. How to make sense of those failures is a massive task and will require insights from fields like policy, sociology, criminology, public health, economics, etc. And we need commonsense regulation of potentially harmful products and behaviors. My limited point here is that the way we talk about issues like stigma and harm reduction is often conceptually muddled, and it would be helpful to get clearer on those terms and concepts or we risk talking past one another and just using these issues as a proxy for broader culture war battles, as was the case for the 1980s-era “War on Drugs.”

Aftab: Your experience at the physician rehab, after your admission to Bellevue, as you describe in The Urge was of great interest to me. I was struck by how your denial and ambivalence was met with the blunt, confrontational, impatient approach of the rehab program. You write:

“To this day, I am not entirely sure how to think of that rehab program. Was Summers too harsh, or did I need to be challenged? Could I have gotten by with just outpatient treatment? Was all that focus on character and personality rehabilitation overkill? I am convinced that I did need to be coerced, in the sense of being faced with a hard choice… I was there because I had to be, at least if I wanted to practice medicine anytime soon. I am glad that I was coerced in that sense; if I hadn’t had the monitoring program in place, I might not have stuck with treatment and entered recovery, and I could have harmed other people, or died myself. Still, I’d like to believe that whatever deeper rehabilitation I experienced had more to do with connection than confrontation.” (pp. 228-229)

And as a reader, I can say that I am not entirely sure how to think of that rehab program either! It seems like confronting hard choices is an important element of overcoming denial. It surprised me how long it took you to fully accept—even to yourself—the severity or extent of your problems with alcohol use. You kept telling yourself some version of, “I was only here because I’d had a manic episode. My drinking hadn’t been the healthiest, but I didn’t need rehab; I was ready for outpatient treatment.” And when you get to the point in the story where you introduce yourself as “Carl, alcoholic,” I find myself cheering as a reader. I imagine that it’s difficult to design rehab programs that force people to confront hard choices and that get the balance between connection and confrontation right in the process.

Fisher: That’s exactly right. I am still humbled by the depths of self-deception I experienced at that time. I do want to emphasize that part of the baffling nature of my self-deception was that it was dynamic and evolved over my treatment experience. I had moments, especially early on in my psychiatric hospitalization, when I was more ready to accept the treatment team’s recommendations. My resistance increased when I got to the rehab and saw what I thought were old-school, harshly confrontational methods.1 That experience tracks with research from Motivational Interviewing, which says that when you tell a patient what to do or how they are wrong, it invokes a “righting reflex,” and it’s better to help elicit the patient’s own reason for change.

Of course, this is complicated when the treatment center also functions in part as a mechanism for social control, as the rehab I went to did—it was a main referral partner of the physician health program that was overseeing my care and ensuring that I wouldn’t pose a danger to patients on my return. You could make a case that confrontation is more appropriate in those cases, but even so, there are ways of helping patients face hard choices (technically, coercion) without harsh confrontation.

Aftab: You briefly talk about your experience with Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy. You had barely heard of IFS and you had kind of dismissed it as “hokey and soft,” and yet it turned out to be a powerful treatment for you.

“I feel like most of my supervisors at Columbia would turn up their noses at it—IFS does not have much of an evidence base, and it has neither the cerebral cachet of psychoanalysis nor the prestige of the more explicitly scientific therapies. But something about it works for me.” (p 295)

I am curious. How did you end up in IFS—rather than some other conventional form of psychotherapy—given your initial unfavorable assessment of it? Second, how can we as a field be more open to such treatment modalities, given our hard-nosed (and perhaps somewhat hypocritical) aspirations to be “evidence-based”? Many psychiatrists and psychologists seem to have a difficult time recognizing the value of such an approach. A further practical challenge is that even if clinicians are open to the possibility that some people can find IFS really helpful, they have no idea how to select the patient who will benefit more from IFS than they would from CBT or psychodynamic psychotherapy. And IFS is just one option among a wide variety of unconventional treatments, all of which may be excellent treatments for some people who we can’t identify in advance. In clinical practice, we operate on a strategy where we try to offer everyone the standard treatments and people who don’t find those helpful are then at the mercy of chance and randomness with regards to what other treatments they come across and can access.

Fisher: How I wound up in IFS is simple: it was just a recommendation from my personal network and had very little to do with my professional life or network. I asked some people I trusted for a therapist who could help with what I was facing. One therapist and Buddhist practitioner that I deeply respected came back with a strong recommendation, I gave the therapist she recommended a try, and it really helped. That kind of serendipity is a common path into treatment, and I think that has implications for how we orient patients to treatment, by the way. People often stumble into a given treatment modality, but we don’t orient them to the framework they’ve landed in. Several branches of clinical psychology do a better job than we psychiatrists do about obtaining informed consent for their specific psychotherapy modality. Some of that can go a little far, but I think it’s a good issue to consider.

I agree that we are very far away from some kind of predictive analytic approach to pairing patients with a specific therapeutic modality. A good psychiatrist should make recommendations for one versus another modality, I would think, but I’m not sure how many do that in a really comprehensive way.

I also recognize that IFS is “unconventional” in the world of evidence-based, academic psychiatry. But it isn’t that unconventional when practiced by a reasonable person. We shouldn’t lump it into the same category as astrology, past-life regression, mediums, etc. A trickier question is: how do we deal with less-conventional but still reasonably reputable treatments?

Aftab: In your discussion of recovery, you discuss how even when you managed sustained sobriety from alcohol, you still felt restless and lonely, you were binging on food or TV, and trying to fill up your days with academic striving. Even being in AA didn’t quite feel satisfying. You were technically in “remission” but it didn’t feel that way to you. Things changed when you started researching a wide variety of recovery experiences and found a way to regain a sense of purpose and a form of spiritual practice that made sense to you. Your Substack has some wonderful discussions on recovery, so I strongly encourage readers to check it out. What I want to say here is that all this reminds me of the other recovery movement, the one for severe mental illness. For a lot of people with severe mood and psychotic disorders, symptom remission is often inadequate on its own. The individuals with serious mental illness I see flourish are typically those who successfully acquire a sense of purpose and a connection to a larger set of values. When you say, “in the end, to fully feel grounded in my recovery, I needed to find a different framework than the one initially offered to me.” (p 294), it makes a lot of sense to me. And yet this is something medicine really struggles to help people with, the ability to recognize the need for multiple frameworks and to create opportunities for people to find a framework that works for them. I am particularly thinking of people with psychotic disorders who find little but coercive control and a bland insistence on taking antipsychotics, and it is no surprise that many seek refuge in programs such as Hearing Voices that allow for, as you put it, “the interconnections and shared experiences in the broader fellowship of recovery.”

Aftab: When you say, “in the end, to fully feel grounded in my recovery, I needed to find a different framework than the one initially offered to me.” it makes a lot of sense to me. And yet this is something medicine really struggles to help people with, the ability to recognize the need for multiple frameworks and to create opportunities for people to find a framework that works for them.

Fisher: Addiction recovery communities have always done a good job of recognizing that we need to go beyond stopping, that mitigating the negatives of “symptoms” is not enough. One question I’ve recently explored is to what extent experiences of flourishing in addiction recovery are specific to people with a history of addiction, versus equivalent to other experiences of wellbeing and flourishing as described in positive psychology. I discussed this at length in my last longer-form post, but there’s some interesting evidence that suggests that there is something special, or at least unique, about the experience of addiction recovery. So the point about shared experiences and fellowship is an important one.

What I have learned in both my own addiction recovery and spiritual practice is that it’s very hard to go it alone. I want to underline the point that it is not just about finding a “framework,” as if the task is solely an intellectual one of reading the right papers and Substacks and arriving at the explanation that works for you. I would like to think that conceptual clarity and rigor are helpful to many people, and we have vastly undersold the capacity and curiosity of the “public” for reading sophisticated and nuanced accounts of mental illness and suffering and how to work with these problems. But in my case, at least, I’ve always needed the human, experiential practice of sharing and working these issues out with other people. I too wish the medical profession did a better job of enabling and supporting those types of groups, and not just in a group therapy or support group format. Perhaps there’s something we could learn here from better versions of 1960s-era community mental health.

Fisher: I want to underline the point that it is not just about finding a “framework,” as if the task is solely an intellectual one of reading the right papers and Substacks and arriving at the explanation that works for you… in my case, at least, I’ve always needed the human, experiential practice of sharing and working these issues out with other people.

Aftab: There is a notable problem of language in the addiction area. I increasingly hear people say that the term “addiction” is unhelping and stigmatizing, and I get it, but at the same time, all of the substitutes seem rather inadequate. “Substance use disorder” is rather sanitized and generally lacking in color (and some people even object to “disorder”). “Harmful substance use” and “substance use problems” seem rather wimpy. Saying “I have a substance use problem” seems devoid of the sort of psychological struggle and insight that go along with declaring, “I am an addict.” What’s the best way to navigate this landscape?

Fisher: Yes, I hear that! I’d just suggest you be as clear, specific, and mindful of context as possible. Here’s how I tend to think of those terms:

“Addiction” is not a mental disorder diagnosis in the DSM. The term is fraught with social and cultural meanings. I think it’s best to let people choose whether they want to identify with the term or not. To me, it depends on whether someone has the subjective sense of being out of control—“powerless” in 12-step language, which is the reference point for many people in recovery and a force significantly shaping cultural understanding—so it should be self-identified, or not. I’m not anti-addiction and I think it’s unrealistic to say we should abandon the term entirely—I identify as a person with addiction!—but I hesitate to label others.

“Substance use disorder” hinges on some subjective criteria (e.g., involving the person’s own intent), but overall, it’s the best we have for a clinical diagnosis from the outside. It’s what to use for formal clinical work, insurance reimbursement, health systems, and the like. We should not assume that SUD equates to addiction. I’m not sure how helpful it is in a research context.

“Harmful substance use” and “substance use problems” work for me as specific descriptors in the public health context. The terms keep the focus on the actual consequences, from DUIs to tobacco-related cancers to overdoses.

So how about the person who wants to acknowledge they have problems with substance use but doesn’t like the label “addiction?” I think it’s up to them. Some people say, “I have a drinking problem, so I can’t drink” or some such thing, why not? It may not carry the same implications of permanence or membership in a particular group. But maybe that’s exactly the issue, and getting curious about what the hang-up is can be instructive.

These problems of language point toward questions about the status of addiction. Is addiction something special, distinct from the rest of the human population? Where to draw the line? Etc. The real way to navigate that landscape is to clarify the underlying nature and meaning of that problem, which is, of course, a work in progress, but I think one that is getting more rigorous and conceptual attention every day. That, at least, is part of what I’m trying to discuss on Rat Park.

Aftab: Finally, I want to ask you about the broken addiction treatment system. You wrote in the book:

“I knew that the addiction treatment system was broken, having experienced it firsthand, but the why was mystifying: Why was there a totally separate system for addiction treatment? Why do we treat addiction differently from any other mental disorder? If everyone seems to know that the system is broken, why isn’t anyone changing it?”

Honestly, it’s not just the addiction treatment system; the mental healthcare system seems broken generally. People wonder about the separation of mental healthcare and physical healthcare as well. But in terms of improving addiction treatment, what do you think needs to happen? If there is an opportunity to change the system, what should we focus on changing?

Fisher: I have some policy recommendations in the book, and considering a clinical and psychiatric audience, there are other good recommendations from organizations like the American Society of Addiction Medicine and the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry for readers who want to go deeper. I'll briefly say the following:

We still drastically need expanded access to care, especially access to medications such as methadone and buprenorphine. That includes removing onerous restrictions on their use.

Care for addiction and other substance problems should also include patient choice and self-determination, and it should be mainstreamed into the rest of general psychiatric and general medical care.

We still need to drastically scale up and support the concrete, evidence-supported harm reduction measures I noted above, such as syringe service programs, naloxone distribution, and supervised consumption facilities. Thorny debates about decriminalization and such aside, there is a lot we could do today to save lives.

We need to move away from a one-size-fits-all model of care and recognize different varieties of recovery. That should not mean a hopeless, nihilistic, “anything goes” attitude toward drug problems. Without coercion or confrontation, we still need to encourage hope for recovery. This is a change at the level of both structure and attitudes.

There’s more I could say. There is so much we could do to save lives, and we should. However, true transformation requires a shift in consciousness and awareness. This is what The Urge is about. I think we need to better respect and understand the varied meanings of addiction, recognizing it as a complex, multifaceted human experience that touches all of us in different ways. Only by embracing this view can we create a more compassionate, effective approach to addiction and recovery.

Aftab: Thank you!

This post is part of a series featuring in-depth interviews and discussions intended to foster a re-examination of philosophical and scientific debates in the psy-sciences. See prior discussions here.

See also:

Like calling patients “King Baby,” which as a sidenote comes from Freud’s phrase, “His Majesty the Baby,” quoted by Harry Tiebout, an early psychiatrist ally of AA

I’m only a medical graduate but I have lived experience and I really feel the addiction recovery to have been the actual special thing about my journey back from DID. To me addiction is the opposite of contentment. I suppose that makes it discontentment! Substance use, self harm, we should come up with a name for being out of control of your body while still being conscious (trance/dissociation?), these are the individual behavioral symptoms. I’m reading Trances People Live and Dr Stephen Wolinsky calls them deep trance phenomena. He also makes it sound like he refers to them as the parts of a IFS/DID system, and in so far as I can tell, he calls them individual consciousness but essentially focuses of autohypnosis. I often feel like I’m intruding on an academic paper with illiterate comments when I reply here but I’ll say sorry and take the chance! Just wondering what you guys think about that.

As a non-specialist in addiction medicine--my specialty is mood disorders--I very much appreciate Dr. Fisher's (and Dr. Aftab's) pluralistic perspective on addictive disorders; e.g., as Dr. Fisher puts it, seeing addiction as "... a complex, multifaceted human experience that touches all of us in different ways. "

And while it's true that the term "biopsychosocial" can veer into vague eclecticism, I do think a bio-psycho-social-spiritual perspective is useful for understanding not only addictive disorders, but also most serious psychiatric conditions in general.1

In this regard, I strongly recommend the recently released book by my colleague, Dr. Cynthia M.A. Geppert, titled "Addiction and the Captive Will: A Colloquy between Neuroscience and Augustine of Hippo." Dr. Geppert shows how Augustine's doctrine of the "captive will" provides a spiritual parallel to current models of addiction involving choice, learning, and abnormal brain function. I think Dr. Fisher and readers of Psychiatry at the Margins will find this scholarly but accessible book very enlightening--and may I add, this recommendation is completely unsolicited!

Best regards,

Ron

Ronald W. Pies, MD

Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry

Lecturer on Bioethics & Humanities

SUNY Upstate Medical University

1. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/can-we-salvage-biopsychosocial-model