A Memoir For the Iatrogenic Age

A Review of Laura Delano's "Unshrunk"

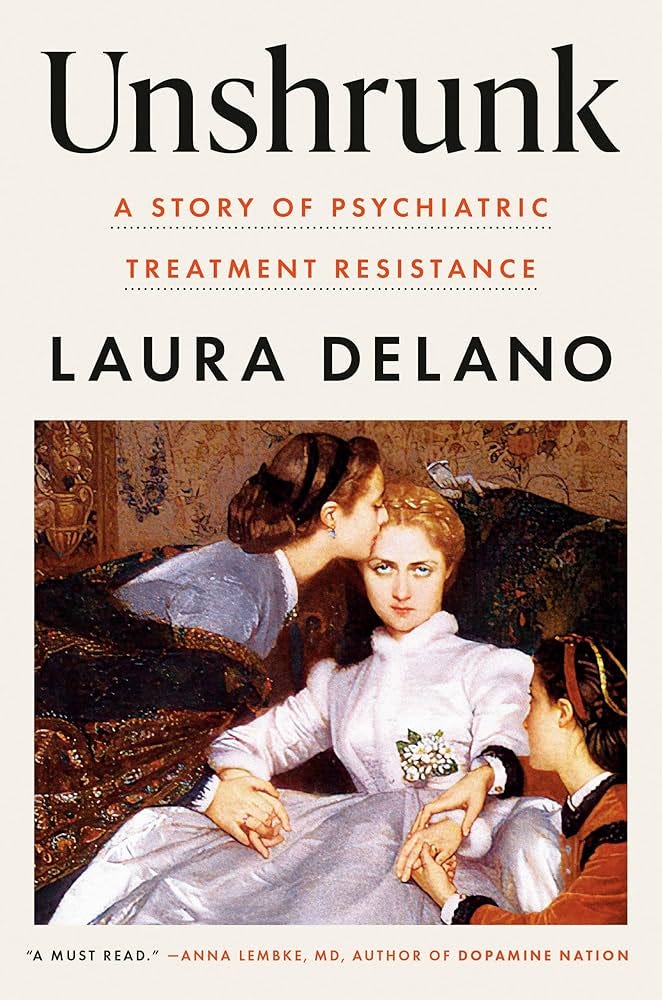

“Unshrunk: A Story of Psychiatric Treatment Resistance” (publication date March 18, 2025, Viking) by Laura Delano is a compelling and troubling memoir of psychiatric patienthood, iatrogenic harm, and finding a meaningful and flourishing life outside of the mental healthcare system.

Delano received treatment from various well-respected psychiatrists and institutions on the East Coast of the United States (including outpatient and inpatient care at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts) in the 90s and 00s, and it’s difficult to argue that the treatment she received was not representative of psychiatric practice at the time. In fact, in many ways, Delano received access to more resources and treatment modalities than are available to the majority of patients in the US.

Delano’s story has left a deep and lasting impression on me. Memoirs have a way of heralding a change in the zeitgeist, and we seem close to a critical mass of people whose lives have been derailed by their experiences of mental healthcare that a memoir about iatrogenesis could become a new cultural touchstone.

Unshrunk chronicles Delano’s fourteen-year entanglement with psychiatric treatment and her eventual decision to reject a medicalized understanding of psychological anguish.

The basic structure of the memoir is deceptively straightforward. In Delano’s own words:

“My youth was shaped by the language of psychiatric diagnosis. Its meticulous symptom lists and tidy categories defined my teens and twenties and determined my future. I believed that my primary condition, bipolar disorder, was an incurable brain disease that would only worsen without medications, therapy, and the occasional stay on a psych ward. This belief was further reinforced each time I heard of the tragic destruction befalling someone who stopped her meds because she thought she could outsmart her disease. I embraced the promises of a psychopharmaceutical solution, welcoming the regimen of pills I ingested in the hope that they’d bring me stability, reliability, functionality.” (xi)

“For fourteen years, I lived tethered to the belief that my brain was broken, and redesigned my entire life around the singular purpose of fixing it… convinced as I was that the only way for my pain to be properly acknowledged was through its medicalization.” (xii)

“The simplest way to put it is that I became a professional psychiatric patient between the ages of thirteen and twenty- seven. The best way to describe what happened next is that I decided to leave behind all the diagnoses, meds, and professionals and recover myself.” (xii)

Delano acknowledges that she hasn’t “recovered” in the traditional sense of the word. She continues to experience intense and troubling emotional states, but the difference is that she no longer finds it valid to think of them as medical disorders, nor does she think that medications or psychotherapies are the appropriate tools to address them. She has embraced her suffering in an Illichian manner.

“It’s been fourteen years since I last took a psychiatric drug or looked in the mirror and saw a list of psychiatric symptoms looking back— and not because I no longer experience intense emotional pain and paranoia and debilitating anxiety and unhelpful impulses, which I still very much do… While a lot in my life has changed for the better as a direct result of healing my brain and body from psychopharmaceuticals, much of what happens in the space between my ears is as dark and messy as ever. (In some cases, more so.)” (xiii-xiv)

“The reason I’m no longer mentally ill is that I made a decision to question the ideas about myself that I’d assumed were fact and discard what I learned was actually fiction. This book is a record of my psychiatric treatment, my resistance to that treatment, and what I’ve learned along the way about my pain.” (xiv)

What went wrong in Delano’s care? An important aspect of Delano’s story is that the harms she experiences are both conceptual and interventional. It is not simply the fact that the treatment she was given failed to sufficiently help her and left her with adverse effects, but much more importantly, the medical language and concepts she was provided to make sense of her difficulties prevented her from meaningfully taking stock of her life.

Delano was told that she has bipolar disorder, an incurable brain disease for which she’ll require medications for the rest of her life.1 It is a travesty that this was ever considered acceptable to tell a patient with a mental disorder, and a travesty still that many patients are told this even today. Even for bipolar disorder, this narrative is frankly untrue, as there is considerable heterogeneity in long-term course, with some people achieving long-standing remission and/or recovery.

Especially in the early years, Delano was given a misleading impression of the diagnostic certainty around bipolar disorder, and in particular, the role of temperamental factors and substance use was not made clear to her. Looking back as a clinician reader (and acknowledging all the limitations this role brings), I am not convinced that Delano’s problems were best characterized as bipolar I disorder, and this is an impression I share with many of Delano’s own treating clinicians. Delano was also diagnosed by several of her clinicians with borderline personality disorder, and it is my impression that her presentation was more in the borderline personality and unspecified mood disorder/bipolar spectrum territory rather than bipolar I.2 In fact, Delano ends her career as a “professional psychiatric patient” while she is being treated at the borderline personality disorder treatment program at McLean under the care of the father of BPD himself, Dr. John Gunderson. This may not matter much to Laura, because she also rejects borderline personality as a diagnosis—not because she doesn’t “meet the criteria,” but because she rejects looking at these behaviors through the medical gaze. And for the public, it only highlights the messy disagreements around diagnoses among professionals. However, any assessment of her story from a clinical point of view needs to take this diagnostic uncertainty into account. The borderline aspect complicates the otherwise straightforward narrative that Delano prefers to tell in the book. It doesn’t change what Delano was told; it doesn’t erase the wrongdoings of her treatment, but for readers of her memoir, it changes the medical understanding of her problems. A memoir of successfully managing borderline personality outside of the healthcare system isn’t quite the same as successfully managing bipolar I manic episodes. The natural history of borderline personality is different from the natural history of bipolar disorder. (If you are one of those clinicians opposed to a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, substitute it for whatever descriptive characterization you prefer for a syndrome of maladaptive traits related to the dimensions of negative affectivity, antagonism, and disinhibition.)

Delano’s psychiatrists showed a pattern of cavalier prescribing, failed to pay adequate attention to adverse effects, subjected Delano to iatrogenic cascade, and appeared to be completely ignorant of the realities of psychotropic withdrawal. (While Delano is taking a mood stabilizer and an antipsychotic, she gets prescribed Ambien as a sedative, and when she starts experiencing daytime drowsiness from the medication, she gets prescribed Modafinil as a stimulant to keep her awake. Yikes!)

Delano spends years in regular psychotherapy, yet her therapists fail to challenge or correct, perhaps even recognize, any of her misleading ideas about mental illness and agency.3

All of the above is made worse by an unhealthy attachment on Delano’s part to the role of a psychiatric patient.4 The mental healthcare system not only failed to address that but actively fed into it. In some ways, Unshrunk is a memoir of Delano’s unstable and intense interpersonal relationship with psychiatry, alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation, and ending with a partial course correction. I do not say this as a way of dismissing Delano’s assessment of the care she received. Delano’s grievances are legitimate as far as her own experiences are concerned.

Delano ultimately—in a sequence of events initiated by reading Robert Whitaker’s Anatomy of an Epidemic—decided to come off all her medications and found a path for herself entirely outside of the mental healthcare system. She strongly related to the idea that the mental healthcare system was making her and keeping her sick5, and this provided her with the motivation and purpose she needed to build a new non-pathological identity and a functional life for herself. Because the possibility that she may ever be able to function outside the mental healthcare system had never been presented to her, her successful ability to do so became, in her mind, a radical proof of the falsehood of psychiatry.6

I can’t help but wonder how Delano’s experiences would have turned out had she been offered an accurate explanation of the nature of mental disorders, psychiatric diagnoses, and psychiatric treatment instead of the bullshit story she was fed. Imagine if she had been told: You can recover, you can be well, and even medications may be unnecessary at some point in your life. We do not have the ability to predict these things on an individual basis, and it is premature to say that you will need them forever. The diagnoses refer to patterns of distressing and disabling experiences and behaviors that are outside our folk psychological norms, and they do not refer to specific disease processes in the brain. Mental health problems exist at an intersection of temperament, physiology, development, and interpersonal challenges and cannot be understood in isolation. Descriptive diagnoses are fuzzy and fluid, especially early in life. They can change over time, and professionals often disagree. Diagnostic categories do not capture your essence or your identity. What you are experiencing is maladaptive, but it does not lack meaning. Engage with your psychological pain, understand what it is trying to tell you, and seek a meaningful life. Medications are imperfect tools that can assist you in the process. They have the ability to both help and harm, and we will work closely to address any problems you experience with them. If the balance ever shifts such that the medications are hurting more than they are helping, you have other resources at your disposal. The treatment of mental illness does not substitute for family, work, education, and community as sources of meaning and fulfillment.

People finding their way out of the mental health system and living well without psychiatric care is a win. I want more of my patients to have outcomes like Laura’s. We should all want more people to achieve what Delano has achieved. And in a better world, the mental healthcare system would facilitate patients in this process as a virtuous ally, rather than the disingenuous opponent it became for Laura.

A memoir like this invites the question of generalization. How many people with mental disorders will be better off discontinuing their medications, stopping psychotherapy, and leaving a medicalized understanding behind? Delano doesn’t say this outright, but readers will be able to pick up on a tendency to assume that most people will be better off if they followed Delano’s footsteps and left the mental healthcare system behind.

How many people in psychiatric care are similar to Delano in this respect? Likely fewer than Delano imagines, I would maintain, but also, the number is probably higher than what I’d like it to be, and this should concern everyone.

Delano gets a little reality check during her brief career as a peer specialist:

“When I started my peer specialist job, I imagined I’d be spending my days helping people stand up against psychiatric coercion, spring themselves from locked wards, and successfully get themselves off meds they’d decided they no longer wanted to take. Within a short time, I realized that this wasn’t the kind of support that most people wanted… I quickly recognized how naive I’d been to assume that all clients of my employer should come off psychopharmaceuticals simply because these drugs are known to cause harm—I saw that I’d come into the job lacking a sense of the complexity of people’s lives.” (p 294)

This is the “partial course correction” I referred to above, and it is encouraging that Delano’s personal experiences had not blinded her to these practical realities. Nonetheless, Delano remains tempted to think that “it had been largely the long-term treatment itself, along with the “medical nemesis” of institutionalized care, that disabled [psychiatric] clients in the first place” (p 295). Most of them can build a “life beyond professionalized, pharmaceuticalized help” if only they had access to the right information, supports, and resources. I do not share that faith, not because I do not wish that this were true, but because the reality of serious and persistent mental illness is impossible for me to ignore as a psychiatric clinician, exceptions notwithstanding.

When Delano reads Whitaker’s Anatomy of an Epidemic, her reaction is:

“Holy shit. It’s the fucking meds.

I’d been confronted with something I’d never considered before: What if it wasn’t treatment-resistant mental illness that had been sending me ever deeper into the depths of despair and dysfunction, but the treatment itself?” (p 212)

It is quite apparent that medications were negatively affecting Laura… her sexuality was inhibited7, she was emotionally blunted, disconnected from her own body, and in a poor state of physical health. Healing from these negative effects was important. But Delano’s own narrative provides evidence that she had long-standing emotional and behavioral issues that preceded the use of the medications8 and that persisted afterwords. What changed was Delano’s own belief in her ability to accept and withstand these difficult emotions. It was a false belief in the permanent, neurological nature of her disability that kept her trapped, one imparted to her by mental health professionals and one she eagerly latched on to herself in a state of vulnerability. What Delano needed was to recover her own agency, and for various reasons, she was not mentally ready to do so earlier in life.

At one point during her psychiatric care, Delano actually meets a psychiatrist who encourages her to think about her problems in a deeper manner.

“In therapy, Dr. Littwin attempted to explore the broader social forces that he felt had shaped my ongoing struggles with body, sexuality, womanhood, and self, and he seemed especially concerned about my knack for dating self-destructive men and drinking myself into blackouts. At the mention of any of this, I swiftly changed the subject, convinced as I was that the source of my troubles was faulty brain pathology. I never took him seriously and frequently skipped appointments… Of all my former psychiatrists, he was the only one who ever invited me to step back and rethink the diagnostic paradigm in which I so deeply believed. I just wasn’t ready yet.” (p 165-166)

And

“I would have scoffed at the proposition that the objective of living is not the absence of pain but the embrace of it—that suffering might not always be a problem to be solved. The years I spent inside the medicalized industry of psychiatric care—what I like to think of as my “psychiatrized” era—had taught me that I lacked the power to endure my struggles on my own, or solely with the help of friends and family.” (p 118)

The mental healthcare system might not have facilitated the development of her agency and may even have hindered it, but it does not mean that the young Delano would naturally have developed her sense of agency on her own. Recovery from mental health problems is in part a matter of discovering one’s agency. The routes to achieving that are different for different people. For Delano herself, an important part of the process was her involvement with Alcoholics Anonymous.

I have been in Dr. Littwin’s shoes numerous times, trying in vain to help people stuck in various problematic states recognize their own agency, their own capacity to bear their anguish, or take ownership of their lives. But people need to be psychologically ready for such a message to penetrate, and sometimes all mental health professionals can do is patiently wait for them to be ready. How people get to the point of readiness is a mysterious process. It is tempting, yet erroneous, to believe that everyone could swiftly progress on the path of agency if only the damned medical professionals got out of the way.

Part of the problem is that it was the Whitaker-Moncrieff worldview that allowed Delano to escape the clutches of her pathologized identity, and she finds it difficult to look at things from outside that framework. One gets the sense that Delano no longer has access to a notion of “psychopathology” that does not refer to brain diseases or chemical imbalances. It becomes difficult to even acknowledge that some people are genuinely helped by psychiatric medications in some non-subjective way.9 Once someone has adopted the Whitaker-Moncrieff worldview, the conceptual resources available to them to acknowledge the reality of mental illness or the therapeutic value of treatment are rendered scarce. Medications can temporarily numb or blunt your anguish and make you feel better in the short term, but in the long term they will make you worse, more prone to relapse, and trap you in disability. These aspects are where the book is at its weakest, in my opinion, and where the book is likely to generate the most antagonism from mainstream medicine. It would be a mistake for professionals to ignore the book for this reason, as Delano’s story has much to teach us about the iatrogenic realities of our work.

Feb 25, 2025: Text briefly edited to clarify that Laura Delano’s BPD diagnosis and treatment are disclosed in the book itself.

See also:

“… many of these things you describe, they are signs of something we call mania.” Dr. Patel, her first psychiatrist, tells her. “She went on to tell me that mania in children typically manifests as intense anger and irritability, impulsivity, outbursts, rapid changes in mood. And on the flip side, my self-harm, isolating behaviors, and hopelessness were signs of depression. Put together, these symptoms were clearly consistent with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, for which there was no cure. I’d have this disease for the rest of my life.” (p 25)

When Delano established care with Dr. Paul Bachman at McLean Hospital:

“bipolar. This would be the diagnosis I believed I had when I left his office at the end of that appointment. But here’s the thing: many years later, when I called Dr. Bachman to request my medical records (which he quickly obliged me, unlike most of my former psychiatrists), I looked at his intake of me and saw “Mood disorder NOS. R/ O bipolar II disorder.”… It appears the only psychiatric diagnosis he officially gave me that day, according to his records, was one he never told me about: borderline personality disorder.” (p 65-66)

Mood Disorder NOS, r/o bipolar disorder, r/o substance-induced mood disorder, r/o borderline personality disorder is likely what I would diagnose in a situation like this, so it was reassuring to see the convergence with Dr. Bachman. (I try not to give an “official” diagnosis of BPD until I get adequate buy-in from the patient after a proper discussion of what the diagnosis entails, for reasons I’ve discussed in the past).

Why was this diagnostic uncertainty not communicated to Delano? Why did she leave with the impression that she had a definitive diagnosis of bipolar disorder?

Dr. Bachman’s diagnostic concerns are revealed in future notes as well. In April 2002, Dr. Bachman noted after Laura had stopped Depakote after running out of refills. “Since diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder is uncertain (borderline personality traits, along with substance use is a more likely diagnosis),” he wrote, “for now she will remain off VPA [valproic acid] and I will observe her clinical progress carefully.” (p 73)

Dr. Bachman’s failure to do so is all the more striking considering that Delano was seeing Dr. Bachman twice a week for psychotherapy in her freshman year!

“my therapists and I operated under the assumption that my emotional and mental difficulties were symptoms of an incurable brain disease for which medication was my first- line treatment, which led me to logically conclude that therapy was at best an enjoyable exercise in connection and conversation and at worst entirely futile.” (p 118)

“Through those early months of 2002, I pursued full actualization of this new life of mental illness with the same zeal for success that had once gotten me excellent report cards, high SAT scores, and top national squash rankings. I relished the relief that came from accepting my diagnosis, sure now that the desperate search for answers to why I was in so much pain was over. I didn’t need to berate myself anymore for being a fuckup, because I wasn’t actually a fuckup. I wasn’t bad, or lazy, or a failure: I was sick. And with the diagnosis came clear next steps that would lead me to feeling better: call up the pharmacy every month for a refill, take my daily doses as prescribed, and keep in good contact with Dr. Bachman.” (p 68)

Obviously, this isn’t a very healthy way of relating to one’s diagnosis or treatment. It is a manifestation of the intense and binary manner in which Delano related to things.

“By the summer of 2007, I’d been a compliant psychiatric patient for six years, spending countless hours in intensive psychotherapy, taking so many different meds in ever- increasing combinations and dosages: Depakote, Seroquel, Prozac, Effexor, Provigil, Ambien, Lamictal, Klonopin, and many more. I’d been inpatient and outpatient and in group after group after group. Where had all of it gotten me? I couldn’t hold down a job. I was utterly unable to make it through a day without obliterating myself with alcohol. I was completely dependent on my family for financial support, adorning myself in the accoutrements of responsible, independent adult life while actually living none of it. I had no meaningful friendships, nor any idea what I cared about. I was physically, sexually, and creatively numb while simultaneously feeling like an emotional live wire, a rabid animal.” (p 128)

“I’ve been off my meds for nearly six years now and I’ve never felt more alive, more connected to myself, more capable. What do you make of this, given that I met the criteria for bipolar disorder, that I wasn’t misdiagnosed?” (p 306) is one of the questions she prepares for her former psychiatrist.

A moving passage in the book is when Laura has her first orgasm after coming off all psychiatric medications.

“A few weeks later, in Bradley’s bedroom, I had the first orgasm of my life. I was twenty-seven. Afterward, as I looked up into the darkness, heart pounding hard, my skin’s sweat cool against the air, I took in a slow breath, bringing the air deep into my lungs, and paused, feeling the thrum of animated neurons inside me. And then a surge of emotion brought the urge to cry with such force to my eyes that I had to hold my breath. And then I couldn’t any longer, overtaken by a sudden, new grief—grief for all the sensation and connection and intimacy and pleasure I’d never had, years that were meant to be the most formative of my personhood, shaping my capacity for love, my relationship to my body, my sexuality, my connection to womanhood, grief for my long legacy of physical vacancy. Grief that I was sometimes so out of body during sex that I wondered if I was being raped.” (p 254)

“My first semester at Harvard, that fall of 2001, can best be described as a willful lurch toward self- annihilation. I drank frequently because it felt like the only reliable way to forget that matriculating at an elite college hadn’t fixed me and now here I was, with no more promising landmarks ahead to bank on as the solution to my pain… On weekends, I sought out ephemeral happiness with each cocaine snort, just one more line, one more.” (p 45)

Things come to a head after she participates in a debutante ball.

“When I awoke the next morning in my grandmother’s guest room on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, I felt emptier than ever before. I stumbled to the bathroom and looked at the smeared mascara, the bags under my eyes, the knotted, sticky hair. There was the acidic aftertaste of vomit in my mouth. My throat and nose, raw from cocaine.

Back in the bedroom, I sat down and began to rock back and forth on the edge of the bed, head in hands, fingers pushing in hard at my temples. There has to be something wrong with me, there has to be, there’s no reason I should be feeling this way, something is wrong with me, what is wrong with me, what is wrong with me, WHAT IS WRONG WITH ME? A deep, low wail started up from my core and I let it out, and rocked, and took in breath, and wailed, and wanted to die so badly, so damn badly. I just need to be dead, I can’t do this, I can’t do this, please please please I can’t do this. My parents ran in at the sounds. They stood panicked before me.

For the first time in as long as I could remember, I looked them dead in the eyes as I said, “Please, I need help.” (p 49-50)

It is clear at this point that this is not a story of “over-medicalizing” “ordinary distress.” What she is experiencing at this point also cannot be explained as a reaction to medications (she barely took them and has been off them for a while) or psychotherapy. This is the raw expression of psychopathology. Delano genuinely needs help here. She doesn’t need a fabricated story about incurable brain diseases or chemical imbalances, but she genuinely needs an empathetic, compassionate, hopeful, psychologically grounded clinical response. The memoir could’ve gone in a very different direction if Delano had received such a response.

“I know that many people feel helped by psychiatric drugs, especially when they’re used in the short term,” Delano writes (p xii, my emphasis).

I have no idea how Delano would feel about your review; that would be fascinating to hear if you ever communicate with her about it. But to me this was the best kind of review one could expect from someone on the other side of the aisle: thoughtful, charitable but also acknowledging your own standpoint and professional observations where that doesn't entirely jibe with hers.

I find antipsychiatry or anti-medication perspectives so much more compelling when it comes through a memoir: you can look at the person's unique experience and testimony, all the rich details, and decide for yourself what to conclude, how much to generalize. *This* person was screwed over in these ways, by *these* psychiatrists (and psychiatry), during *this* era. And has this wisdom to offer us about it. What can we learn, and still leave as open questions? It's almost like the cautionary-tale version of Gordon Paul's famous dictum: what treatment by whom was most harmful for this individual with that specific problem, etc. etc.

I really appreciate the way you communicate the complexities and heterogeneities of mental health care while maintaining compassion and hope.